By Clarence Lusane

By Clarence Lusane

By now, we know that the history featured in textbooks and children’s literature is often riddled with myths, distortions, and outright fabrications. Many children’s history books reinforce rather than debunk incorrect information and stereotyping ideologies. A recent book, Master George’s People: George Washington, His Slaves, and His Revolutionary Transformation by Marfé Ferguson Delano (National Geographic Children’s Books, 2013), is a sad example of this tendency. The book is targeted for young people, ostensibly to teach them about the first president and the fact that he held people in slavery. To appeal to young people, the book discusses the role of children on the Washington plantation at Mount Vernon and gives profiles of a number of individuals who were enslaved to George and Martha Washington.

Although it is a worthwhile effort to teach young people about slavery and the involvement of the first president in that institution, Delano compromises that goal in a number of critical ways. To begin with, the title implies a certain legitimacy to Washington’s “ownership” of people. Legally, morally, and politically, people who were enslaved by and to Washington were property without any rights, equal opportunity, or ability to live free. They were not Washington’s “people.” They were his property.

The use of the appellation “master” in the title elides the real power dynamic that existed, by which the term was a mask. Referring to Washington as “master” was more an obligation than any choice. He was indeed the master of the plantation that oversaw hundreds of enslaved people who had no human rights whatsoever.

It seems the principal objective of the book, reflected in its subtitle, George Washington, His Slaves, and His Revolutionary Transformation, is to acknowledge Washington’s role as a slave owner but mollify it by describing what the author sees as his radical growth into antislavery, or even abolitionism, by his passing in 1799. To that end, the last pages of the book focus on Washington’s will, in which he stated that all of the enslaved that he owned outright would be freed after both he and Martha Washington died. This is viewed ultimately as redemption.

On the issue of slavery, the book compares Washington, favorably, to other revolutionary leaders of the time. This includes Founding Fathers such as Thomas Jefferson, chief author of the Declaration of Independence, and James Madison, key theoretician and writer of the U.S. Constitution. Delano states, correctly, that although both Jefferson and Madison were conflicted, like Washington, over the morality and humanity of slavery, they did not free their slaves even at their time of death. As she states, “Only one slave-holding Founding Father [Washington] found the courage to do that,” failing to add that they were freed only after his and Martha’s deaths. This is the “revolutionary transformation” that the subtitle implies.

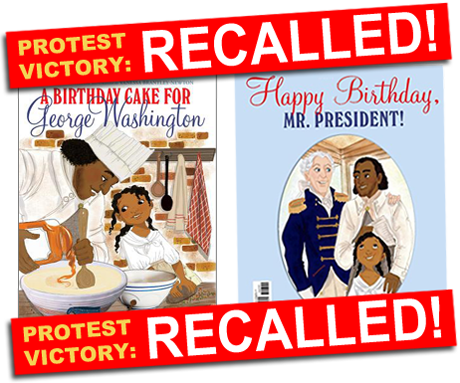

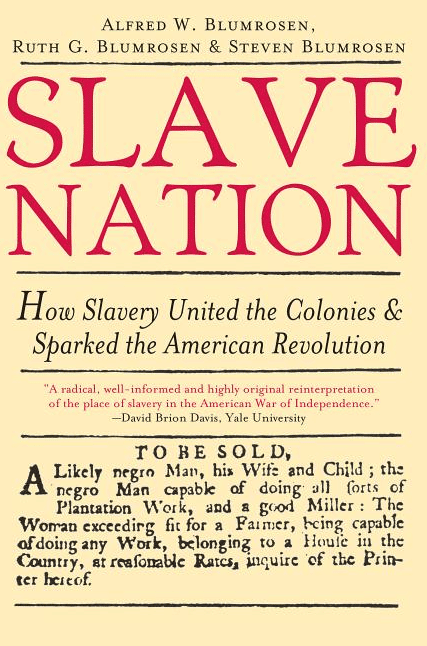

Close-up view of book cover.

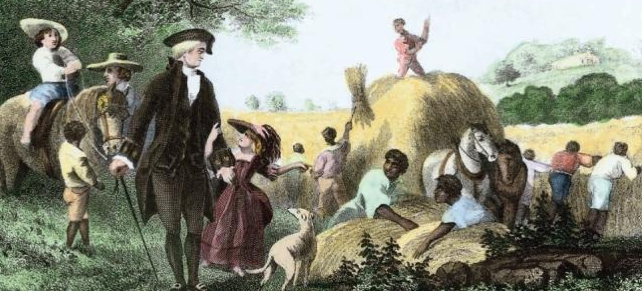

The images in the book communicate the book’s mission. As the front jacket notes, the picture on the cover “depicts an idyllic view of George Washington and his African American slaves at Mount Vernon, but the reality was more complex.” Given the truth of this explanation, why use the picture in the first place? The picture shows nine enslaved individuals including children working in the field while Washington casually strolls with a young white girl with another young white boy on a horse close by. The image is one of serenity and contentment.

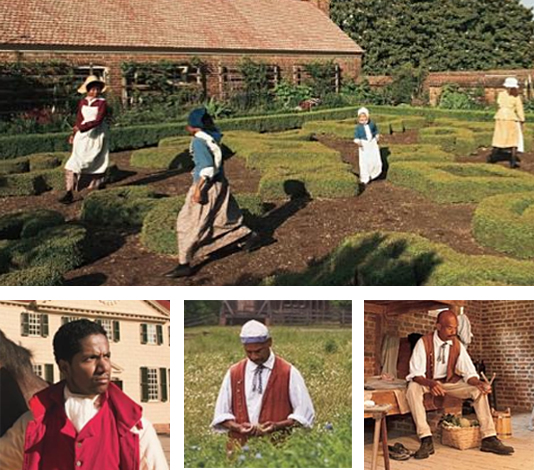

Samples of photo reenactments from “Master George’s People.”

Many of the pictures in the book are of slave reenactors — actors pictured doing various tasks around the plantation, e.g., working in the field, tending animals, sewing, and cooking. Most are smiling or have neutral faces. You would be hard-pressed to find an unhappy person.

The book focuses on the individual lives of those who were enslaved — what the book jacket calls the “fascinating portraits of cooks, overseers, valets, farmhands, and more” — rather than the institution or system that enslaved them. This includes individuals such as William Lee, who accompanied Washington during the war and after as a valet; Christopher Sheels; and Charlotte, a young woman, beaten by the farm manager at Mount Vernon with Washington’s approval. Washington wrote the farm manager and stated that if any of the enslaved were “impertinent, correction . . . must be administered.”

Washington would be the first of a long line of pre-Civil War presidents who failed to address the most crucial issue in the country: slavery. This was due in large part because most of them were slave owners themselves, including Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Tyler, Polk, Taylor, Van Buren, and Harrison.

Missing from the book, in large part, is the brutality and dehumanization of slavery. Although Delano points repeatedly that slavery was bad, she fails to convey the all-sided harshness that was the daily life of those enslaved. The book also makes only passing reference to the resistance of people who were enslaved. She notes the escape of Hercules, Washington’s cook, and Oney Judge, a young girl who was enslaved to Martha Washington, but for the most part the daily rebellions and overbearing repression do not come across.

Read more about race and class issues not addressed in the U.S. Constitution in Bill Bigelow’s Constitution Day article.

Delano also does not mention the role of Washington in drafting the original U.S. Constitution that sanctioned slavery and forbade non-slave states to harbor people who had escaped. In other words, at opportune moments for Washington to express and debate publicly bringing an end to slavery he never did.

The most disturbing element of the book is that it tends to treat slavery as an issue of personal choice. In other words, Washington made some bad choices early on (or had them forced on him) and then he made good choices toward his final days. In fact, slavery was an institution that existed beyond individuals’ whims and wishes. It qualitatively and profoundly shaped the founding and evolution of the United States until it was ended in 1865. When given the option, Washington facilitated and supported the institution rather than challenge it. The real heroes of the period were the abolitionists who called and fought for the immediate end of slavery, and the enslaved who resisted in myriad ways.

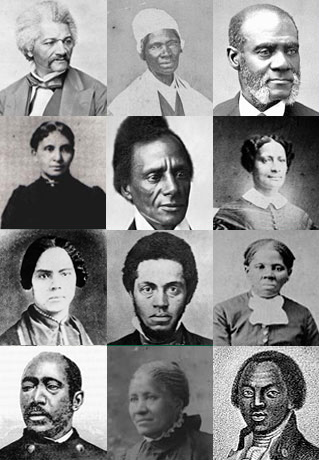

A few of the black abolitionists. Read more.

Fortunately, there have been efforts to acknowledge the role of enslaved people in the building of the nation and in particular some of its most iconic buildings. On December 18, 2007, Congress passed legislation that recognized the enslaved labor that helped to build the U.S. Capitol. A space in the central rotunda was named “Emancipation Hall” and, on June 16, 2010, two plaques were placed in the hall that read “This original exterior wall was constructed between 1793 and 1800 of sandstone quarried by laborers, including enslaved African Americans who were an important part of the workforce that built the United States Capitol.”

In addition, at the new Liberty Bell Pavilion in Philadelphia, a plaque has been installed that recognizes the individuals who were enslaved to Washington during the time of his presidency when he lived there. The permanent exhibit, “President’s House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation,” won after years of struggle, opened in 2010.

Very soon, the White House may join Congress and Philadelphia in finally recognizing the important role of enslaved people in building the White House. Congressman Andre Carson (D-IN) has drafted legislation that would have the White House publicly acknowledge the contribution of the black carpenters, bricklayers, and other enslaved workers who constructed the building in the 1790-1800 period, and helped rebuild it after it was largely destroyed by the British in 1814. This would probably take the form of a plaque similar to the ones that exist in the Capitol. Such a step would go a long way in publicly recognizing the horrific history of slavery in the United States, a history that has too often been ignored or misrepresented.

Dr. Clarence Lusane is the program director for Comparative and Regional Studies at American University. He teaches courses in comparative race relations, modern social movements, comparative politics of the Americas and Europe, and jazz and international relations. He is a national columnist for the Black Voices syndicated news network. Lusane has authored a number of books including The Black History of the White House (City Lights, 2010). Read more.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn