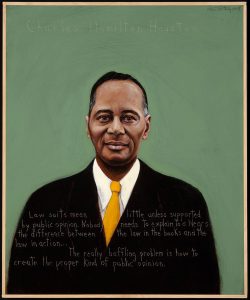

By Hasan Kwame Jeffries

This article on films is reprinted with permission from Understanding and Teaching the Civil Rights Movement.

Documentaries and movies are highly effective tools for teaching civil rights history. They make the movement come alive, breathing life into the nameless and faceless masses who mobilized and organized for change. People are generally aware of Rosa Parks’s role in the Montgomery bus boycott but are wholly unaware of the thousands of Black domestic workers who made victory possible by refusing to ride the buses for an entire year. Films add depth and dimension to the famous leaders who spearheaded the struggle, such as Martin Luther King Jr. Everyone knows who Dr. King is, but too few know him beyond sound bites from his “I Have a Dream” speech. And films generate empathy by capturing and conveying deep emotion, such as the paralyzing fear brought about by night riders. It is one thing to read about racial terror; it is another thing entirely to see it in high definition.

The pedagogical power of film is strengthened when documentaries and movies are paired with one another. The lessons learned in the former are reinforced in the latter. Pairing films also sharpens critical analysis of popular narratives of the movement. People are conditioned to believe what they see on screen. Pairing films challenges this basic assumption when what appears in a documentary, such as the presence of Black women in leadership positions, fails to show up in a movie.

An explosion of films on civil rights history over the last twenty-five years has created abundant options for using film in the classroom. Scores of documentaries have been produced, touching on subjects ranging from the origins of the movement to its aftermath. Although fewer movies have been produced, and their subject matter has been less varied, the selection is still strong.

Of course, not all films are equal. There are good ones that get the basic history correct and great ones that totally disrupt the Master Narrative. There are also terrible ones that reinforce the Master Narrative, and God-awful ones that simply fabricate history. Yet nearly all of them are useful, with the best ones revealing the truth about the past, and the worst ones exposing entrenched falsehoods. Thus, films about the movement, from the exceptional to the dreadful, that examine a broad cross section of subjects, from the origins of racism to contemporary civil rights struggles, can significantly deepen understanding of civil rights history.

Tedx Talk by Hasah Kwame Jeffries on “Hard History”

This 13-minute talk by Hasan Kwame Jeffries can be a useful companion to this critical list of films about the Civil Rights Movement and institutionalized racism in U.S. history.

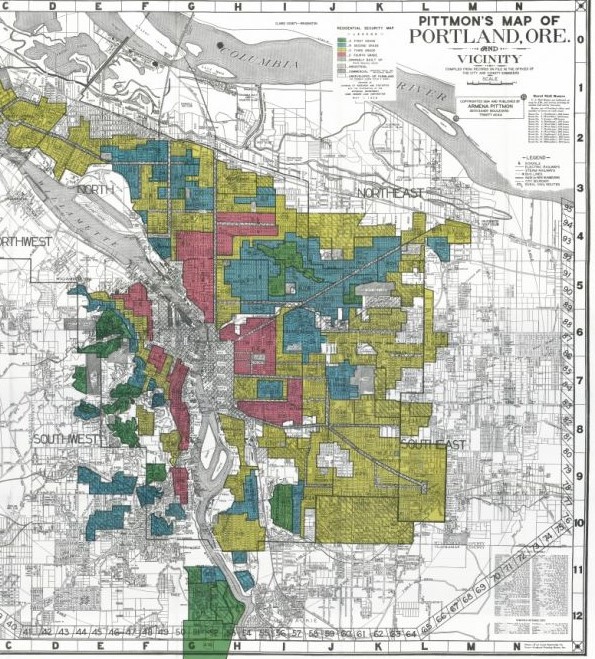

Racism has shaped the contours of America from the earliest days of the Republic, fueling the need for a civil rights movement. Race: The Power of an Illusion (2003) is a great primer for discussing the role of racism in American society. The three-hour documentary begins by explaining race as a pseudoscientific invention designed to justify European capitalist exploitation of African labor. It then pivots toward racism, moving quickly beyond personal prejudice to look at the racialization of political structures and economic systems. Finally, it looks specifically at the racialization of the housing market to illustrate the harmful effect racial discrimination has had on contemporary African Americans.

Racism has shaped the contours of America from the earliest days of the Republic, fueling the need for a civil rights movement. Race: The Power of an Illusion (2003) is a great primer for discussing the role of racism in American society. The three-hour documentary begins by explaining race as a pseudoscientific invention designed to justify European capitalist exploitation of African labor. It then pivots toward racism, moving quickly beyond personal prejudice to look at the racialization of political structures and economic systems. Finally, it looks specifically at the racialization of the housing market to illustrate the harmful effect racial discrimination has had on contemporary African Americans.

I Am Not Your Negro (2017) explores racism in a completely different way, from the perspective of civil rights-era essayist James Baldwin. But it is equally effective as a springboard for an opening discussion on the need for a civil rights revolution. Using Baldwin’s searing words, the documentary draws viewers in, making the pain of the Black past feel present. For some, Baldwin’s indictment of white Americans for their commitment to white supremacy will confirm long-held suspicions. For others, it will be a revelation. But for all, it will prompt deep introspection, a necessary ingredient for frank and honest conversation.

Civil rights protest challenged contemporaneous patterns and practices of racial discrimination. For much of the twentieth century, this meant taking on Jim Crow. The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow (2002) provides a thorough overview of Jim Crow and the Black response to it. The four-hour documentary explores the history of segregation from emancipation through World War II, chronicling both its formal and informal manifestations in the South and beyond. The second and third episodes, which examine the Black experience from Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 through the start of the NAACP’s school desegregation campaign in the 1930s, is particularly useful for establishing the movement’s precursors and preconditions.

Civil rights protest challenged contemporaneous patterns and practices of racial discrimination. For much of the twentieth century, this meant taking on Jim Crow. The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow (2002) provides a thorough overview of Jim Crow and the Black response to it. The four-hour documentary explores the history of segregation from emancipation through World War II, chronicling both its formal and informal manifestations in the South and beyond. The second and third episodes, which examine the Black experience from Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 through the start of the NAACP’s school desegregation campaign in the 1930s, is particularly useful for establishing the movement’s precursors and preconditions.

Dramatizations of Black life during the era of legal segregation help make clear that Jim Crow was much more than just a bundle of unfair laws. Mudbound (2017) explores personal interactions across and on either side of the color line in the Mississippi Delta during World War II. The film’s gaze is intimate, providing a close look at the racialized customs that simultaneously separated and tied together Black tenant farmers and white landowners, showing how Jim Crow linked Black fates to white fortunes. The Great Debaters (2007) chronicles the trials and triumphs of the debate team at Wiley College, a historically Black college in Marshall, Texas, during the Depression. One scene in particular, “The Pig Farmer,” effectively re-creates the kind of life-threatening, random encounters that African Americans often had with whites and is worthy of showing on its own. Something the Lord Made (2004), the story of pioneer heart surgeon Vivien Thomas, explores the less dramatic, daily indignities of segregation, rendering unmistakable the ways that Jim Crow customs, as practiced by both individuals and institutions, stifled human potential at great cost to society. The movie parallels the documentary Partners of the Heart (2002) but is far more emotionally engaging.

Two films set in the Jim Crow era that are inspiring tales of persistence and perseverance but are far less useful as overviews of the period are Hidden Figures (2016) and Loving (2016). Although both films treat their subjects thoughtfully and compassionately, and each has the added benefit of revolving around Black women, which too few films do, neither provides a clear enough sense of the scale and scope of segregation to effectively convey the intractable nature of Jim Crow. Another film set in the Jim Crow era that is of no use at all is The Help (2011). The movie fixates on normalizing white privilege and Black subservience and completely marginalizes the Mississippi freedom movement.

Violence was the cornerstone of Jim Crow. Whites resorted to it to regulate Black behavior, control Black labor, and steal Black wealth. The documentary Banished: How Whites Drove Blacks Out of Town in America (2006) examines three incidents of early twentieth-century racial violence that resulted in Black landowners losing their lives and property. It also shows how the land grab impeded Black economic upward mobility for generations. An Outrage (2017) takes a personal look at lynching through the eyes of its victims and their descendants. It is a hauntingly moving portrayal of Jim Crow’s strange fruit.

The kind of mob violence that led to lynching can be hard to fathom, but Rosewood (1997), which depicts the 1923 racial pogrom in the all-Black town of Rosewood, Florida, reveals the mechanics of lynch mobs, including the rapidity with which they formed, and captures the unspeakable horror of their murderous rampages.

White sheriffs rarely protected the targets of racial violence, and white judges and juries almost never provided justice to victims. Instead, they worked to uphold Jim Crow laws and enforce Jim Crow customs. Few cases illustrate this better than that of the Scottsboro Boys. Scottsboro: An American Tragedy (2000) recounts the conviction of nine innocent Black teenagers accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. Slavery by Another Name (2012) takes a broader look at the justice system under Jim Crow by detailing the ways white southerners used convict leasing to reestablish and maintain white supremacy after Reconstruction. It is a harrowing account of brutal capitalist excess.

White sheriffs rarely protected the targets of racial violence, and white judges and juries almost never provided justice to victims. Instead, they worked to uphold Jim Crow laws and enforce Jim Crow customs. Few cases illustrate this better than that of the Scottsboro Boys. Scottsboro: An American Tragedy (2000) recounts the conviction of nine innocent Black teenagers accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. Slavery by Another Name (2012) takes a broader look at the justice system under Jim Crow by detailing the ways white southerners used convict leasing to reestablish and maintain white supremacy after Reconstruction. It is a harrowing account of brutal capitalist excess.

A southern prison labor camp, not unlike Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Prison Farm, is the backdrop for Life (1999), a comedy featuring Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence as two would-be bootleggers sentenced to life in prison for a murder they did not commit. The film touches on many of the themes discussed in Slavery by Another Name, including judicial malfeasance, creating the opportunity for critical analysis of popular representations and misrepresentations of segregation.

Depicting Black suffering during the Jim Crow era makes clear why African Americans were so desperate for change. Highlighting Black organizing during the same period is just as important because it demonstrates African Americans’ refusal to accept the status quo. Birth of a Movement: The Battle Against America’s First Blockbuster (2017) describes the effort led by William Monroe Trotter, a Boston-based activist and newspaper editor, to ban D. W. Griffith’s white supremacist propaganda film Birth of a Nation. Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind (2000) examines the life of the Jamaican-born activist, who through the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and its newspaper, the Negro World, spread the gospel of Black nationalism and Pan-Africanism. Much like these documentaries, 10,000 Black Men Named George (2002), a fictionalized account of civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph’s effort to organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in the 1920s, introduces viewers to a grassroots campaign that not only challenged Jim Crow but also helped create the organizing infrastructure that enabled the civil rights movement to flourish years later.

Depicting Black suffering during the Jim Crow era makes clear why African Americans were so desperate for change. Highlighting Black organizing during the same period is just as important because it demonstrates African Americans’ refusal to accept the status quo. Birth of a Movement: The Battle Against America’s First Blockbuster (2017) describes the effort led by William Monroe Trotter, a Boston-based activist and newspaper editor, to ban D. W. Griffith’s white supremacist propaganda film Birth of a Nation. Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind (2000) examines the life of the Jamaican-born activist, who through the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and its newspaper, the Negro World, spread the gospel of Black nationalism and Pan-Africanism. Much like these documentaries, 10,000 Black Men Named George (2002), a fictionalized account of civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph’s effort to organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in the 1920s, introduces viewers to a grassroots campaign that not only challenged Jim Crow but also helped create the organizing infrastructure that enabled the civil rights movement to flourish years later.

World War II looms large in civil rights history. “Deadly Calling,” the third episode of The War (2007), provides a useful overview of the Black wartime experience at home and abroad, albeit interspersed between stories of military developments overseas. The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords (1999) probes much deeper by tracking the unheralded effort of Black journalists to advance democracy for black soldiers on the frontlines and for Black citizens on the home front. In Their Own Words: The Tuskegee Airmen (2012) uses oral history to zero in on the civil rights hardships and military heroism of Black flyers. By contrast, the major motion picture Red Tails (2012) omits the airmen’s fight against racial discrimination on U.S. soil before, during, and after their time in the army. An egregious oversight, it nonetheless creates an opportunity to use the film to interrogate the idea that Black military service and sacrifice were enough to rid whites of racial prejudice.

When northern Black servicemen and servicewomen who had been stationed in the South returned home, they were unable to escape racial discrimination. Like the waves of Black southerners who had left the region during the war years, they could not outrun white supremacy. To be sure, a different kind of Jim Crow reigned up north, but it was still Jim Crow. Neither New York nor Cleveland nor Oakland turned out to be the fabled Promised Land.

Goin’ to Chicago (1994) demystifies northern Jim Crow by examining the lives of a group of older Black Chicagoans who migrated from the Mississippi Delta. A common experience in nearly all of their personal stories is housing discrimination. The Pruitt-Igoe Myth (2011), which explores the creation and collapse of a massive public housing complex in St. Louis, masterfully unpacks housing discrimination, including the central role played by the state and federal governments. The movie Fences (2016) is the perfect complement to these documentaries. Set in Pittsburgh, it shows how working-class African Americans tried to get the most out of life despite the constant pressure of racial discrimination. Sports animated the protagonist in Fences, Troy Maxson, like nothing else in life. Baseball in particular was his salvation and refuge, and to hear him tell it, he was spectacular. But sports did not unburden him of the weight of racism, just as it did not relieve those in the real world who either toiled in segregated Black leagues or broke into white professional leagues. Their struggle provides a window through which to view not only the intersection of race and sports but also Jim Crow America, especially in the North.

Goin’ to Chicago (1994) demystifies northern Jim Crow by examining the lives of a group of older Black Chicagoans who migrated from the Mississippi Delta. A common experience in nearly all of their personal stories is housing discrimination. The Pruitt-Igoe Myth (2011), which explores the creation and collapse of a massive public housing complex in St. Louis, masterfully unpacks housing discrimination, including the central role played by the state and federal governments. The movie Fences (2016) is the perfect complement to these documentaries. Set in Pittsburgh, it shows how working-class African Americans tried to get the most out of life despite the constant pressure of racial discrimination. Sports animated the protagonist in Fences, Troy Maxson, like nothing else in life. Baseball in particular was his salvation and refuge, and to hear him tell it, he was spectacular. But sports did not unburden him of the weight of racism, just as it did not relieve those in the real world who either toiled in segregated Black leagues or broke into white professional leagues. Their struggle provides a window through which to view not only the intersection of race and sports but also Jim Crow America, especially in the North.

Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (2004) chronicles the first Black heavyweight boxing champion’s brazen exploits in and out of the ring during the first part of the twentieth century. Jesse Owens (2012) follows the journey of the 1936 Olympic gold medalist in track and field from Cleveland to Berlin, highlighting the many obstacles Jim Crow placed before him. Olympic Pride—American Prejudice (2016) pushes beyond the Owens narrative to share the experiences of the seventeen Black athletes, including two Black women, who joined Owens on the 1936 U.S. Olympic team. Only the Ball Was White (1980) provides an excellent overview of the Negro Leagues, a key example of a Black parallel institution. “Shadow Ball,” the fifth “Inning” of Baseball (1994), also explores the Negro Leagues and its star players but in greater depth. Jackie Robinson (2016) offers a detailed glimpse of the on-the-field achievements and off-the-field civil rights advocacy of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ legend. Black Magic (2008) looks at the history of basketball at historically Black colleges and universities and the impact desegregation had on the sport, Black athletes, and Black coaches, while Breaking the Huddle: The Integration of College Football (2008) does the same for football. And Muhammad Ali: Through the Eyes of the World (2001) tells of the far-reaching impact that the boxing great’s stand against white supremacy and opposition to the Vietnam War had on people.

Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (2004) chronicles the first Black heavyweight boxing champion’s brazen exploits in and out of the ring during the first part of the twentieth century. Jesse Owens (2012) follows the journey of the 1936 Olympic gold medalist in track and field from Cleveland to Berlin, highlighting the many obstacles Jim Crow placed before him. Olympic Pride—American Prejudice (2016) pushes beyond the Owens narrative to share the experiences of the seventeen Black athletes, including two Black women, who joined Owens on the 1936 U.S. Olympic team. Only the Ball Was White (1980) provides an excellent overview of the Negro Leagues, a key example of a Black parallel institution. “Shadow Ball,” the fifth “Inning” of Baseball (1994), also explores the Negro Leagues and its star players but in greater depth. Jackie Robinson (2016) offers a detailed glimpse of the on-the-field achievements and off-the-field civil rights advocacy of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ legend. Black Magic (2008) looks at the history of basketball at historically Black colleges and universities and the impact desegregation had on the sport, Black athletes, and Black coaches, while Breaking the Huddle: The Integration of College Football (2008) does the same for football. And Muhammad Ali: Through the Eyes of the World (2001) tells of the far-reaching impact that the boxing great’s stand against white supremacy and opposition to the Vietnam War had on people.

Sports movies abound, making it possible to pair nearly all of these documentaries with direct cinematic counterparts. Race (2016), 42 (2013), and Ali (2001) are biopics about Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, and Muhammad Ali, while Glory Road (2006) and Remember the Titans (2000) revolve around the integration of college basketball and high school football. But every one of these films treat civil rights more or less the same — racism is reduced to personal prejudice practiced by a handful of rednecks; it is overcome by Black athletes through nonviolent perseverance; and it is rejected by whites once they witness African American athletes performing at a high level. The usefulness of these films, then, is mainly as prompts for analyzing the shortcomings of normative narratives of the persistence and eventual demise of Jim Crow.

Much like movies on race and sports during the Jim Crow era, movies specifically about the civil rights movement tend to follow the Master Narrative, with storylines revolving around preachers and presidents and a heavy emphasis on nonviolence. Documentaries about the movement, however, are generally much better, shifting the focus away from great men and broadening the range of strategies and tactics beyond nonviolence.

Eyes on the Prize remains the gold standard for documentaries on the civil rights movement. Its fourteen hour-long episodes draw on a rich array of primary source material, including original broadcast news footage and interviews with movement leaders and foot soldiers, to weave together an accessible overview of the movement. It is not, however, without shortcomings. At times it is overly event and leader driven, especially its early episodes, causing the complexity of the movement, including its geographic diversity, to be lost. The pacing is also a bit slow for today’s younger viewers, who have grown up watching films with more visual activity. It is best used, then, selectively, in segments, as an introduction to key events and people.

Eyes on the Prize remains the gold standard for documentaries on the civil rights movement. Its fourteen hour-long episodes draw on a rich array of primary source material, including original broadcast news footage and interviews with movement leaders and foot soldiers, to weave together an accessible overview of the movement. It is not, however, without shortcomings. At times it is overly event and leader driven, especially its early episodes, causing the complexity of the movement, including its geographic diversity, to be lost. The pacing is also a bit slow for today’s younger viewers, who have grown up watching films with more visual activity. It is best used, then, selectively, in segments, as an introduction to key events and people.

By contrast, Soundtrack for a Revolution (2009), which tells the story of the movement through freedom songs, pulsates with energy. Civil rights music inspired, encouraged, and energized movement participants, who are called on here to explain their purpose and importance. Although contemporary artists, such as John Legend, perform the songs, the arrangements are traditional. Unfortunately, so too is the narrative arc. The film adheres too closely to the Montgomery to Memphis framework, privileging the experiences of Dr. King above all else.

Lee Daniels’s The Butler (2013), whose lead character, Cecil Gaines, serves as a valet to eight U.S. presidents, is one of a small handful of movies that attempt to engage the entire history of the civil rights movement. Not surprisingly, its take on the movement is conventional, emphasizing decisions made in the Oval Office over those made at mass meetings. Indeed, the movement does not even seem to exist until Gaines arrives at the White House, and it loses steam completely when Black Power emerges. In this sense, it is a classic depiction of the Master Narrative and should only be shown as such. At the same time, the film re-creates a few pivotal movement moments that are almost always ignored on screen, most notably the nonviolent direct action workshops led by Rev. James Lawson in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1959.

Most treatments of the civil rights movement are far less ambitious than Eyes, Soundtrack, or The Butler. Rather than tackling the subject as a whole, they focus instead on a specific event, historical figure, or both. Beginning with school desegregation, The Road to Brown (1990) traces the history of the NAACP’s southern school desegregation campaign, which culminated in the US Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. The film introduces Charles Hamilton Houston, the architect of the NAACP’s strategy, and shines a light on the segregated communities involved in the cases. Mr. Civil Rights: Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP (2014) recounts the NAACP’s long legal battle to desegregate southern schools that Marshall, a protégé of Houston, helped lead. The biopic Marshall (2017) dances around the edges of this history, choosing instead to focus on Marshall’s early courtroom activism outside the South. Laurence Fishburne’s one-person play, Thurgood (2011), however, fits perfectly with these documentaries. It is unusually comprehensive in its coverage of the courtroom challenge, and Fishburne’s performance is masterful. In fact, Thurgood is strong enough historically and theatrically to be shown on its own.

It is well established that the civil rights movement did not begin with Brown, but the Supreme Court ruling, along with the murder of Emmett Till and the start of the Montgomery bus boycott one year later, are critically important to the movement’s evolution. Together, they mobilized new constituencies and created new possibilities for pursuing change.

The Murder of Emmett Till (2003) details the events surrounding the lynching of the fourteen-year-old Chicago boy at the hands of two white men in Money, Mississippi, making direct connections to the Great Migration and rabid white resistance to Brown. The filmmaker’s interview with Mamie Till, young Emmett’s mother, in which she describes the impact of her son’s murder, is particularly powerful. “Awakenings, 1954–1956,” the first episode of Eyes on the Prize, discusses the death of Till and the emergence of the Montgomery bus boycott, showing how their combined force pushed the movement in a new direction. The movie Boycott (2001), which is based on historian Stewart Burns’s edited collection of oral histories with movement participants, stands out as the best film or documentary on the Montgomery protest. It makes clear the mechanics of the movement, depicts the central role of women, and portrays King as he was — a reluctant leader struggling to catch up to his people.

Returning to school desegregation, the crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957 is explained succinctly in “Fighting Back, 1957–1962,” the second episode of Eyes on the Prize. This segment nicely sets up Nine from Little Rock: Pioneers of Desegregation (1964). This documentary short, filmed seven years after the highpoint of the conflict, profiles the lives of the nine Black students who desegregated Central High School. Little Rock Central: 50 Years Later (2007) shares the perspectives of students and community members five decades removed from the crisis, creating an opportunity to discuss school segregation and desegregation in a contemporary context.

The Little Rock Nine were the vanguard of southern student protest, which exploded into full public view with unimaginable energy in February 1960 with the lunch counter sit-ins. A Force More Powerful (1999), which examines a half-dozen, nonviolent, direct action campaigns across the globe during the twentieth century, draws on rare archival footage to take viewers inside the Nashville sit-in movement, revealing the practicalities of a nonviolent campaign. Meanwhile, Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker (1981) introduces viewers to veteran activist Ella Baker, the guiding force behind the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Baker infused SNCC with a commitment to grassroots democratic organizing, enabling the organization to catapult the movement forward in the early 1960s.

Some of the tough decisions that SNCC activists had to make are beautifully dramatized in Freedom Song (2000), a fictionalized account of a SNCC direct action and voter registration campaign. Rather than focusing on a single, large-scale, mobilizing event, Freedom Song hones in on the slow, hard work of organizing, making grassroots activism visible, a rarity in movies. Freedom Song also touches directly on the Freedom Rides, making it a terrific companion for Freedom Riders (2011), which tells the story of the more than four hundred African American and white activists who traveled to the South in 1961 to challenge segregation in interstate travel.

Some of the tough decisions that SNCC activists had to make are beautifully dramatized in Freedom Song (2000), a fictionalized account of a SNCC direct action and voter registration campaign. Rather than focusing on a single, large-scale, mobilizing event, Freedom Song hones in on the slow, hard work of organizing, making grassroots activism visible, a rarity in movies. Freedom Song also touches directly on the Freedom Rides, making it a terrific companion for Freedom Riders (2011), which tells the story of the more than four hundred African American and white activists who traveled to the South in 1961 to challenge segregation in interstate travel.

Young people remained at the forefront of the struggle in 1963. In Birmingham, Alabama, they forced white elected officials and business leaders to desegregate downtown by taking to the streets and filling the city’s jails. Mighty Times: The Children’s March (2004, out of print) documents their courage and heroism. There was, however, a steep price to be paid, and four young people paid it with their lives when Klansmen bombed Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church. 4 Little Girls (1997) revisits that horrible moment, recalling the lives lost and explaining the far-reaching and long-lasting impact of their deaths.

Young people remained at the forefront of the struggle in 1963. In Birmingham, Alabama, they forced white elected officials and business leaders to desegregate downtown by taking to the streets and filling the city’s jails. Mighty Times: The Children’s March (2004, out of print) documents their courage and heroism. There was, however, a steep price to be paid, and four young people paid it with their lives when Klansmen bombed Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church. 4 Little Girls (1997) revisits that horrible moment, recalling the lives lost and explaining the far-reaching and long-lasting impact of their deaths.

The next year, in St. Augustine, Florida, young people conducted wade-ins at beaches and a swim-in at a hotel pool to desegregate America’s oldest city. Often overlooked, the struggle in “Florida’s Birmingham” drew national attention to the brutality that undergirded Jim Crow, helping to bring about the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Dare Not Walk Alone (2008) places St. Augustine back in the national narrative, connecting the actions of local people with those of Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon B. Johnson. But only the first half of the eighty-minute documentary examines the movement in 1964. The second half looks at local Black life nearly fifty years later, pointing out the underlying reasons for the persistence of poverty, rising incarceration rates, and failing schools. A sobering reminder of the movement’s limits, this part of the film creates an opportunity to reflect on the long-term impact of the fight for civil rights.

Whereas St. Augustine has been underemphasized, Freedom Summer has been overemphasized, owing to the participation of large numbers of northern white students who joined the effort to break segregationists’ stranglehold on Mississippi. Freedom Summer (2014) chronicles the events of those intense months, from the formation of freedom schools to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s Atlantic City challenge. Freedom on My Mind (1994) covers the same subject but looks more closely at the years leading up to 1964, providing a much better sense of the Mississippi movement’s evolution. The experiences of one white activist are the subject of An Ordinary Hero: The True Story of Joan Trumpauer Mulholland (2013), creating space for dialogue about the role of whites in the movement.

Whereas St. Augustine has been underemphasized, Freedom Summer has been overemphasized, owing to the participation of large numbers of northern white students who joined the effort to break segregationists’ stranglehold on Mississippi. Freedom Summer (2014) chronicles the events of those intense months, from the formation of freedom schools to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s Atlantic City challenge. Freedom on My Mind (1994) covers the same subject but looks more closely at the years leading up to 1964, providing a much better sense of the Mississippi movement’s evolution. The experiences of one white activist are the subject of An Ordinary Hero: The True Story of Joan Trumpauer Mulholland (2013), creating space for dialogue about the role of whites in the movement.

The flip side of white participation in the freedom struggle — white opposition to it — is covered in Spies of Mississippi (2014), which examines the state of Mississippi’s use of intelligence gathering, economic coercion, political intimidation, and murder to thwart the freedom struggle. Neshoba: The Price of Freedom (2011) turns a spotlight on organized racial terror groups by looking at the infamous murder of three civil rights workers by Klansmen at the start of Freedom Summer.

More movies have been made about civil rights in Mississippi than have been made about any other civil rights topic, but with the notable exception of Freedom Song, none are especially good, and a few are just plain bad. Of the latter, Mississippi Burning (1988), possibly the most watched civil rights film of all time, tops the list, having managed to make the movement’s success hinge totally on the wit and wisdom of white FBI agents. It is worth showing only to interrogate a fabrication of movement history.

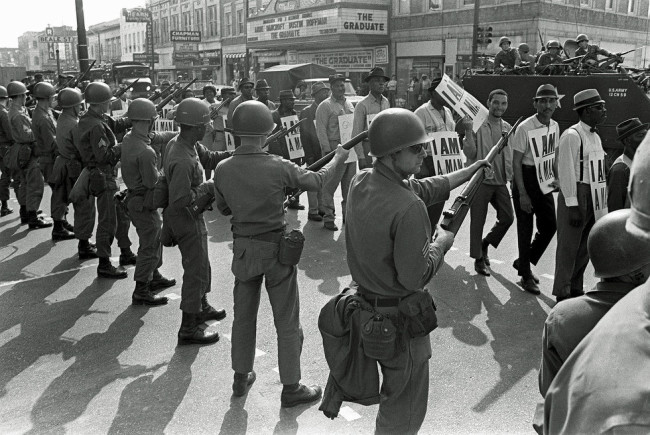

Selma (2015) is everything that Mississippi Burning is not. It centers African Americans — they are the primary shapers of their own destiny, and it portrays the FBI with much greater accuracy, as more adversary than ally. These reasons alone make it worth watching. But as a depiction of the 1965 Selma voting rights campaign, it is not without flaws. Local Alabama activists take a backseat to national leaders, and advocates of self-defense, especially within SNCC, are depicted as overly emotional and irrational. This is not totally unexpected because the movie is actually a biopic, a portrayal of Dr. King revolving around his civil rights leadership and nonviolent approach to change. As such, it works well with the documentaries Citizen King (2005) and King in the Wilderness (2018), which examine the final years of King’s life; The March (2013), which goes behind the scenes of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom; and At the River I Stand (1993), a chronicle of King’s time with striking Memphis sanitation workers shortly before his death. It also pairs nicely with King: A Filmed Record . . . Montgomery to Memphis (1970), which pulls together rare footage of King delivering some of his most important speeches, including “I Have A Dream.”

As seen in Selma, King’s outsized presence in civil rights narratives obscures key elements of the freedom struggle, chief among these being self-defense. Negroes with Guns: Rob Williams and Black Power (2004) addresses this oversight by sharing the story of Williams’s armed defense of the Black community in Monroe, North Carolina, and full-throated advocacy of self-defense via the radio waves. Deacons for Defense (2003), a fictionalized account of the Deacons for Defense and Justice, the armed self-defense group founded in Jonesboro, Louisiana, in 1964 to protect local movement participants, including nonviolent activists, complements Negroes with Guns perfectly. The story of the Deacons, which is ably captured here, demonstrates the ways armed self-defense could make nonviolent direct action possible and compel reluctant federal officials to act on behalf of African Americans.

But it is neither the Deacons nor Rob Williams who come most immediately to mind when thinking about African Americans and armed self-defense, but rather Malcolm X. Even in Selma, the former spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (NOI) makes a cameo appearance as the foil to King’s nonviolence. Malcolm, of course, was much more than a voice of Black rage; he was an astute political thinker with a constantly evolving worldview, which comes across clearly in Malcolm X: Make It Plain (1994), the most comprehensive documentary on his life. Spike Lee’s artful Malcolm X (1992) is also a viable option for introducing Malcolm as it cleaves closely to The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

But it is neither the Deacons nor Rob Williams who come most immediately to mind when thinking about African Americans and armed self-defense, but rather Malcolm X. Even in Selma, the former spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (NOI) makes a cameo appearance as the foil to King’s nonviolence. Malcolm, of course, was much more than a voice of Black rage; he was an astute political thinker with a constantly evolving worldview, which comes across clearly in Malcolm X: Make It Plain (1994), the most comprehensive documentary on his life. Spike Lee’s artful Malcolm X (1992) is also a viable option for introducing Malcolm as it cleaves closely to The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Malcolm lived his entire life in the Midwest and the Northeast. Treatments of his life, therefore, can be used to offer insights into the northern freedom struggle. So too can The Hate That Hate Produced (1959), a news exposé on the NOI. Although the program frames the group as a Black supremacist cult, the interviews with Malcolm, NOI spiritual leader Elijah Muhammad, and NOI members are revelatory in terms of perspectives on racism from Black northerners who rejected integration.

The view of moderate, mainstream Black northerners comes across in two biographies. The first is Adam Clayton Powell (1989), which explores the life and politics of the outspoken civil rights activist who represented Harlem in Congress in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. And the second is The Power Broker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights (2012), which delves into the political machinations of the head of the National Urban League.

The sentiments of everyday Black northerners trapped in declining, deindustrializing, urban centers are discernible through documentaries on the uprisings of the mid- to late 1960s. July ’64 (2006) offers insights into the thoughts of ordinary African Americans in Rochester, New York, through its exploration of the causes and consequences of the three-day rebellion that took place there in the summer of 1964. Revolution ’67 (2007) does the same for African Americans living in Newark, New Jersey, during that uprising three years later. Both documentaries work with Detroit (2017), a severely flawed dramatization of the murder of three African Americans by police at the Algiers Motel during the 1967 Motor City rebellion. The documentaries make visible what is rendered invisible in Detroit, most notably the local movement and the institutionalized nature of police terror.

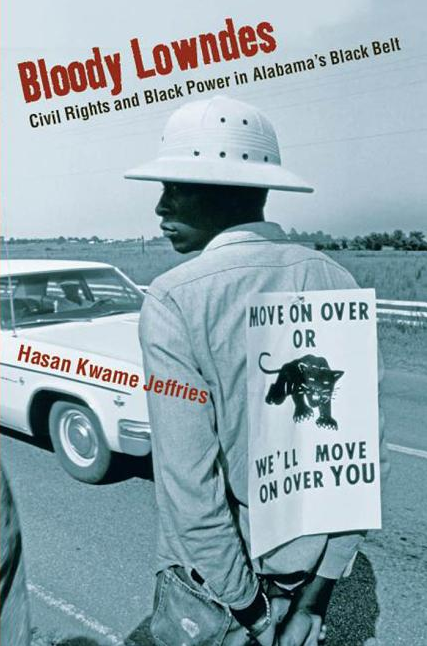

Urban uprisings offer a convenient entry point for discussing the transition from civil rights to Black Power, but jumping immediately from one to the other misses Black Power’s southern roots. “Out of the Shadows,” the first episode of Black America since MLK: And Still I Rise (2016), and “The Time Has Come, 1964–1966,” the seventh installment of Eyes on the Prize, explain the genesis of Black Power in SNCC’s Lowndes County, Alabama, organizing project. The Black America episode also introduces the Oakland, California, Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP), the most iconic organization of the Black Power era.

The Black Panthers are generally treated harshly in movies. In Forrest Gump (1994), and more recently in The Butler, they are mocked as gun-toting, wannabe revolutionaries who contributed nothing to the movement other than violence. Scenes from both films are worth showing as examples of gross mischaracterizations in popular portrayals of civil rights and post–civil rights Black radicalism. The scene in Forrest Gump is especially worth deconstructing because it is the only exposure most students have to the BPP and Black Power.

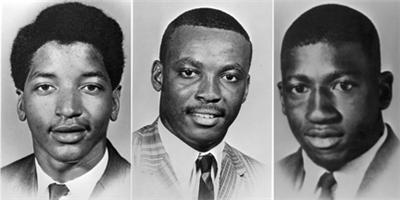

Samuel Hammond, Henry Smith, both SCSU students, and Delano Middleton, a local student at Wilkinson High School.

A notable exception to these kinds of distorted depictions emanating from Hollywood is Blood Done Sign My Name (2010), an account of white racial violence and Black protest in the small town of Oxford, North Carolina, in 1970. The film casts Black Power protest as an extension of civil rights activism and treats Black Power advocates as serious political thinkers. Both of these points are also well made in Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre, 1968 (2008), which examines Black activism at South Carolina State University and investigates the murder of three students by state troopers. The emphasis on student activism in both films makes pairing them together work for the purpose of discussing the emergence of Black Power.

“Move On Up,” the second episode of Black America Since MLK, covers the 1970s, providing a good sense of those areas of Black life where civil rights victories had made a substantial difference and those areas where radical change was still needed. The final three episodes of Eyes on the Prize do similar work, but in a bit more detail. Meanwhile, The Black Power Mixtape, 1967–1975 (2011), a compilation of interviews with activists and movement footage shot by Swedish journalists during the period, offers a narrower kind of overview of the era by analyzing Black Power ideology as a response to conditions left unaddressed by the civil rights movement.

Finally, there are several noteworthy documentaries on contemporary topics through which to explore the legacy of the movement. The development of hip-hop, from the streets of the Bronx to the concert stages of Europe, is chronicled in Hip Hop Evolution (2016). Letter to the President (2005) and Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982—1992 (2017) examine the devastating impact that Reaganomics had on the African American community, the former through rap music and the latter through the 1992 Los Angeles uprising. The cultural influence and economic exploitation of Black athletes at predominantly white universities is the subject of The Fab Five (2011). OJ Made in America (2016) ties all of these themes together into a coherent and compelling narrative of Black life from the 1960s through the 1990s by chronicling football legend O. J. Simpson’s phenomenal rise and spectacular fall. The destruction wrought in New Orleans by decades of discriminatory housing policy and the federal government’s grossly negligent response to Hurricane Katrina is explored in When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006). The House I Live In (2012) and The 13th (2016) offer micro- and macro-level views of mass incarceration. The Central Park Five (2012) and Every Mother’s Son (2004) take intimate, deeply personal looks at unconstitutional police practices and their collateral consequences. And Whose Streets? (2017) tells the story of the Ferguson, Missouri, uprising in 2014, from the killing of eighteen-year-old Michael Brown by local police to the birth of the Movement for Black Lives, from the point of view of the activists who led it.

There are very few major motion pictures on contemporary civil rights topics as powerful as Fruitvale Station (2013), a heart-wrenching dramatization of Oscar Grant III’s last day alive. The twenty-two-year-old African American was shot and killed by Bay Area transit police on New Year’s Day in 2008. The film is the perfect complement to any of the documentaries on contemporary topics, especially the ones on mass incarceration and policing, including Whose Streets?

Documentaries and movies are incredible resources for teaching civil rights history, and never before have so many been available for classroom instruction. The best ones can truly deepen understanding of the movement, but even the worst ones can be used to make clear what the struggle was about. The right documentary, paired with the right movie, can help students wrap their minds around even those aspects of the movement that are the hardest to comprehend.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries is associate professor of History at The Ohio State University where he teaches courses on the Civil Rights and Black Power Movement. Jeffries is the author of Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt (NYU Press, 2009) and the editor of Understanding and Teaching the Civil Rights Movement (University of Wisconsin Press, 2019). Jeffries has worked on several public history projects including the renovation of the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee. He hosts the podcast Teaching Hard History: American Slavery for the Southern Poverty Law Center.

From Understanding and Teaching the Civil Rights Movement edited by Hasan Kwame Jeffries. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2019 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

I’d also suggest for you list the documentary film, “Faubourg Treme: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans.” Executive produced by Wynton Marsalis and Stanley Nelson. Written and Directed by Lolis Eric Elie and Dawn Logsdon The story of the first Civil Rights Movement in the 1800s, the home of Homer Plessy (Plessy v. Ferguson’s separate but equal lawsuit) and the birthplace of jazz. Winner of many awards and broadcast on PBS.