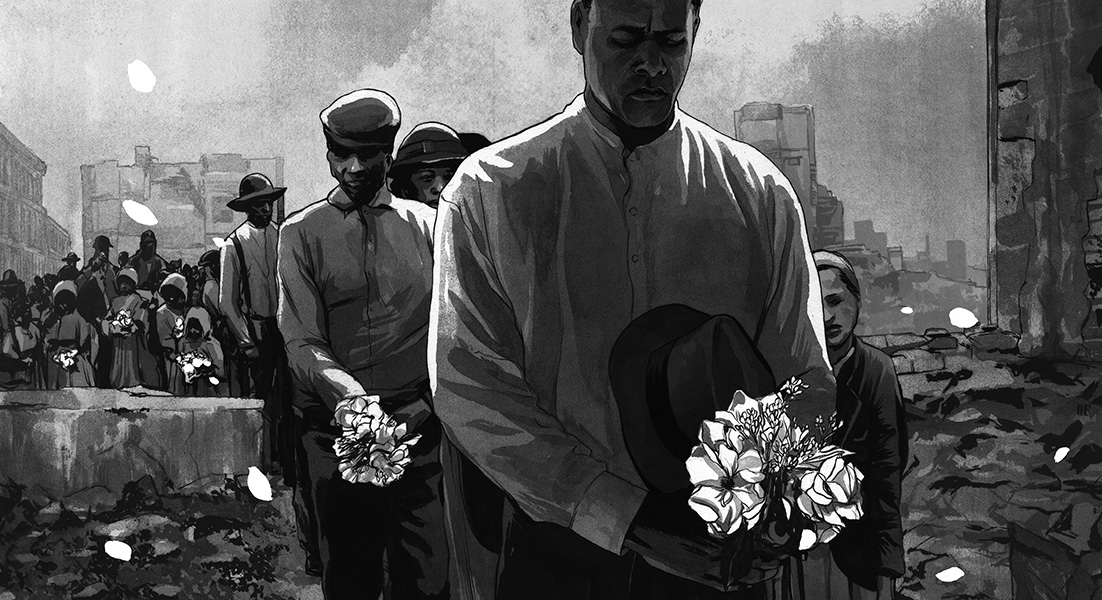

Memorial Day, illustration for The New York Times. Used here with permission of the artist and (c) Owen Freeman,

Americans understand that Memorial Day, or “Decoration Day,” as my parents called it, has something to do with honoring the nation’s war dead. It is also a day devoted to picnics, road races, commencements, and double-headers. But where did it begin, who created it, and why?

As a nation we are at war now, but for most Americans the scale of death and suffering in this seemingly endless wartime belongs to other people far away, or to people in other neighborhoods. Collectively, we are not even allowed to see our war dead today. That was not the case in 1865.

At the end of the Civil War the dead were everywhere, some in half buried coffins and some visible only as unidentified bones strewn on the killing fields of Virginia or Georgia. Americans, north and south, faced an enormous spiritual and logistical challenge of memorialization. The dead were visible by their massive absence. Approximately 620,000 soldiers died in the war. American deaths in all other wars combined through the Korean conflict totaled 606,000. If the same number of Americans per capita had died in Vietnam as died in the Civil War, 4 million names would be on the Vietnam Memorial. The most immediate legacy of the Civil War was its slaughter and how we remember it.

War kills people and destroys human creation; but as though mocking war’s devastation, flowers inevitably bloom through its ruins. After a long siege, a prolonged bombardment for months from all around the harbor, and numerous fires, the beautiful port city of Charleston, South Carolina, where the war had begun in April, 1861, lay in ruin by the spring of 1865. The city was largely abandoned by white residents by late February. Among the first troops to enter and march up Meeting Street singing liberation songs was the Twenty First U. S. Colored Infantry; their commander accepted the formal surrender of the city.

1865 view of the Union soldiers graves at Washington Racecourse. Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress.

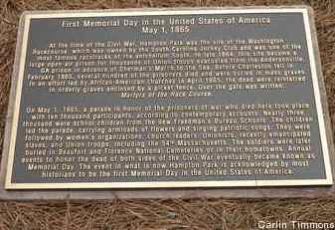

Thousands of Black Charlestonians, most former slaves, remained in the city and conducted a series of commemorations to declare their sense of the meaning of the war. The largest of these events, and unknown until some extraordinary luck in my recent research, took place on May 1, 1865. During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the planters’ horse track, the Washington Race Course and Jockey Club, into an outdoor prison. Union soldiers were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of exposure and disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand. Some twenty-eight Black workmen went to the site, re-buried the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

Then, Black Charlestonians in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged an unforgettable parade of 10,000 people on the slaveholders’ race course. The symbolic power of the low-country planter aristocracy’s horse track (where they had displayed their wealth, leisure, and influence) was not lost on the freedpeople. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

At 9 a.m. on May 1, the procession stepped off led by three thousand Black schoolchildren carrying arm loads of roses and singing “John Brown’s Body.” The children were followed by several hundred Black women with baskets of flowers, wreaths and crosses. Then came Black men marching in cadence, followed by contingents of Union infantry and other Black and white citizens. As many as possible gathering in the cemetery enclosure; a childrens’ choir sang “We’ll Rally around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and several spirituals before several Black ministers read from scripture. No record survives of which biblical passages rung out in the warm spring air, but the spirit of Leviticus 25 was surely present at those burial rites: “for it is the jubilee; it shall be holy unto you. . . . in the year of this jubilee he shall return every man unto his own possession.”

Following the solemn dedication the crowd dispersed into the infield and did what many of us do on Memorial Day: they enjoyed picnics, listened to speeches, and watched soldiers drill. Among the full brigade of Union infantry participating was the famous 54th Massachusetts and the 34th and 104th U.S. Colored Troops, who performed a special double-columned march around the gravesite. The war was over, and Decoration Day had been founded by African Americans in a ritual of remembrance and consecration. The war, they had boldly announced, had been all about the triumph of their emancipation over a slaveholders’ republic, and not about state rights, defense of home, nor merely soldiers’ valor and sacrifice.

According to a reminiscence written long after the fact, “several slight disturbances” occurred during the ceremonies on this first Decoration Day, as well as “much harsh talk about the event locally afterward.” But a measure of how white Charlestonians suppressed from memory this founding in favor of their own creation of the practice later came fifty-one years afterward, when the president of the Ladies Memorial Association of Charleston received an inquiry about the May 1, 1865 parade. A United Daughters of the Confederacy official from New Orleans wanted to know if it was true that Blacks had engaged in such a burial rite. Mrs. S. C. Beckwith responded tersely: “I regret that I was unable to gather any official information in answer to this.” In the struggle over memory and meaning in any society, some stories just get lost while others attain mainstream dominance.

Officially, as a national holiday, Memorial Day emerged in 1868 when General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, the Union veterans organization, called on all former northern soldiers and their communities to conduct ceremonies and decorate graves of their dead comrades. On May 30, 1868, when flowers were plentiful, funeral ceremonies were attended by thousands of people in 183 cemeteries in twenty-seven states. The following year, some 336 cities and towns in thirty-one states, including the South, arranged parades and orations. The observance grew manifold with time. In the South, Confederate Memorial Day took shape on three different dates: on April 26 in many deep South states, the anniversary of General Joseph Johnston’s final surrender to General William T. Sherman; on May 10 in South and North Carolina, the birthday of Stonewall Jackson; and on June 3 in Virginia, the birthday of Jefferson Davis.

Over time several American towns, north and south, claimed to be the birthplace of Memorial Day. But all of them commemorate cemetery decoration events from 1866. Pride of place as the first large scale ritual of Decoration Day, therefore, goes to African Americans in Charleston. By their labor, their words, their songs, and their solemn parade of flowers and marching feet on their former owners’ race course, they created for themselves, and for us, the Independence Day of the Second American Revolution.

The old race track is still there — an oval roadway in Hampton Park in Charleston, named for Wade Hampton, former Confederate general and the white supremacist Redeemer governor of South Carolina after the end of Reconstruction. The lovely park sits adjacent to the Citadel, the military academy of South Carolina, and cadets can be seen jogging on the old track any day of the week. The old gravesite dedicated to the “Martyrs of the Race Course” is gone; those Union dead were reinterred in the 1880s to a national cemetery in Beaufort, South Carolina. Some stories endure, some disappear, some are rediscovered in dusty archives, the pages of old newspapers, and in oral history. All such stories as the First Decoration Day are but prelude to future reckonings. All memory is prelude.

The old race track is still there — an oval roadway in Hampton Park in Charleston, named for Wade Hampton, former Confederate general and the white supremacist Redeemer governor of South Carolina after the end of Reconstruction. The lovely park sits adjacent to the Citadel, the military academy of South Carolina, and cadets can be seen jogging on the old track any day of the week. The old gravesite dedicated to the “Martyrs of the Race Course” is gone; those Union dead were reinterred in the 1880s to a national cemetery in Beaufort, South Carolina. Some stories endure, some disappear, some are rediscovered in dusty archives, the pages of old newspapers, and in oral history. All such stories as the First Decoration Day are but prelude to future reckonings. All memory is prelude.

—By David W. Blight. Blight is professor of American history at Yale University and director of the Gilder-Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition. Blight has won major historical awards, including the Bancroft Prize and the Frederick Douglass Prize. He is the author of many books on U.S. history, including Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, and an adviser for the Zinn Education Project Teach Reconstruction campaign.

Posted at the Zinn Education Project website with permission of the author from The First Decoration Day.

Related Resource

Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory by David W. Blight (Harvard University Press, 2002) offers a full chapter on the history of Memorial Day. Here is the publisher’s description of the book, which also helps to explain why the Memorial Day story shared in this article has been hidden from public memory:

“No historical event has left as deep an imprint on America’s collective memory as the Civil War. In the war’s aftermath, Americans had to embrace and cast off a traumatic past. David Blight explores the perilous path of remembering and forgetting, and reveals its tragic costs to race relations and America’s national reunion. In 1865, confronted with a ravaged landscape and a torn America, the North and South began a slow and painful process of reconciliation. The ensuing decades witnessed the triumph of a culture of reunion, which downplayed sectional division and emphasized the heroics of a battle between noble men of the Blue and the Gray. Nearly lost in national culture were the moral crusades over slavery that ignited the war, the presence and participation of African Americans throughout the war, and the promise of emancipation that emerged from the war. Race and Reunion is a history of how the unity of white America was purchased through the increasing segregation of Black and white memory of the Civil War. Blight delves deeply into the shifting meanings of death and sacrifice, Reconstruction, the romanticized South of literature, soldiers’ reminiscences of battle, the idea of the Lost Cause, and the ritual of Memorial Day. He resurrects the variety of African-American voices and memories of the war and the efforts to preserve the emancipationist legacy in the midst of a culture built on its denial.” Read more.

“Forgetting Why We Remember” by David W. Blight, New York Times, May 29, 2011.

This is an interesting history of the 1st Decoration Day, although it seems a few commenters want to refute it. As a historian, it seems Prof. Blight uncovered an event which may not have been highly regarded by those in charge of the confederacy. In fact, they may have disregarded the event altogether, so to get into a discussion that the Ladies organization did it first is simply useless. Imagine that with the war just ending, there was much confusion and emotion around how to address the freedmen who had fought and died for their freedom as well as the many issues regarding the treatment of the newly freed women, children, and men of South Carolina. The commemorative effort made by these people at that particular time illustrates a hopeful and optimistic view of the future, which, history shows, was systematically snatched away over the years. But at the time of this event, there was no way any of them could have done more than show respect for those who had died fighting for their own freedom. Did other events take place? Probably so. However, it seems Blight refers to this particular event as “the First” because of the DATE of the event. Prof. Blight tells us something unknown as it relates specifically to the newly freed African Americans, and how they commemorated the dead at that crucially important point in history.

Thank you Mr. Emitt Wyatt.

One of the overlooked truths is that our

“Creator” is colorblind?..These God-fearing women were set to do the right thing for

all who risked their life in battle, no matter the skin color or uniform color…thank the good Lord for them.?…and thank you again Mr. Wyatt for bringing this to light

Great information. I always thought Decoration Day was commemorating WW1. And Memorial day as it was called combined both events. Reading history is not a listing of events of the past, it is an explanation of who, how, and why we are what we are today.

Had these events of the past not happened, who knows what the United States would look like if it was here at all.

May 1 1865 is the day of honor for the Civil War Soldiers and all future fallen military persons. The Black Charleston freed men and women set the stage for the observance. Memorial Day established…

Thank you. This article is amazing as well as informing. Some things I did not know. I remember calling Memorial Day “Decoration Day” as a young girl in grade school. At that time we marched to the Cemetery carrying flowers. We then placed the flowers of graves. I am a Senior Citizen now and as I reflect on the then and now I am a little saddened because the true meaning of Memorial Day no longer penetrates the hearts and minds of some. History in itself is one thing that we all should know in some phases or another. After all if we do not know where we came from, how can we know where we are going..so we have to take a look back.

People have been decorating graves with flowers for thousands of years. The first proposal for an annual holiday to commemorate the dead of the Civil War came from the Ladies Memorial Association of Columbus, GA. The proposal was widely published in newspapers throughout the country. The April 12, 1866 New York Times mentioned the preparations taking place across the south.

The holiday was widely observed on April 26, 1866. The observance was reported in the Georgia cities of Atlanta, Augusta, Americus, Macon and Columbus. It was also reported to have occurred in Montgomery, AL; Memphis, TN; Lexington, KY and many smaller towns and villages of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.

Columbus, MS decorated a day early. likely due to the 25th being mistakenly reported in several newspapers. Other cities in south chose different days. Richmond, VA chose May 10 and Petersburg, VA chose June 9 in response to the call of the Ladies Memorial Association.

John A. Logan spoke at a July 4, 1866 event where he mentioned “traitors in the south” decorating graves with flowers. He was well aware of the news reports of the observances. On May 8, 1866 the Baltimore Sun first used the term “memorial day” in describing the tribute proposed by the “a lady of Columbus, Georgia”

The event in Charleston, SC on May 1, 1865 was basically the same as the Gettysburg, PA event of November 19, 1863 that gave us the Gettysburg Address. Both were cemetery dedications. They are one time events and not meant to be repeated. David Blight confessed in the May 26, 2012 New York Times that he has no evidence that the Charleston event led to Logan’s call for a national holiday. The evidence does, however, show that Logan responded to the events inspired by the Ladies Memorial Association of Columbus, GA.

By some accounts, the ladies of Columbus visited the cemetery in late April of 1862, decorating the graves of Confederate soldiers who were killed at Shiloh, or succumbed from their wounds after the battle. They resumed the practice on April 25, 1866. Noticing that the graves of Union soldiers went undecorated, the women of Columbus placed flowers on the burial plots of their former enemies.

Columbus wasn’t the only American town to remember the war dead in that spring of 1866. But it could be argued that the Mississippi commemoration had the most impact. The simple act of generosity and reconciliation was noted in Horace Greely’s New York Tribune and it inspired Frances Miles Finch’s poem, “The Blue and the Gray,” which became required memorization for generations of school children.

The Columbus event also influenced the establishment of a formal Memorial Day. In 1868, General John A. Logan, leader of a veterans group called the Grand Army of the Republic, issued General Order Number 11 designating May 30 as a memorial day “for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion.” The first national celebration of the event took place on May 30th of that same year, at Arlington National Cemetery.

Originally known as Decoration Day, the commemoration officially became Memorial Day at the turn of the century. By that time, the practice of decorating the graves of dead soldiers had become customary throughout the nation. But the annual act of remembrance might have never occurred, except for a bloody Civil War battle, and an act of kindness by a group of southern women.

Any dates prior to this date?

******************************************

One of the early Decoration Day commemorations took place at Friendship Cemetery in Columbus, Mississippi, on April 25, 1866. This event made national news, and the following is one of the articles about it.

Springfield Republican (MA), June 2, 1866:

The Columbus (Miss.) Sentinel abuses the women of that place for having placed flowers on the graves of the Union dead, at the same time that they decorated the graves of their own friends. The Vicksburg Herald, on the contrary, which is edited by an ex-Confederate soldier, says: ‘We envy not the narrow-heartedness of journals that can find fault with so noble an action. To our mind, it speaks volumes for the purity of woman’s character. Our ladies are not politicians – they are Christian women. And while engaged in decorating and preserving the graves of our soldiers, they thought not of war-like strife, nor of vengeance against the dead. They only knew, as they viewed those solitary graves of strangers in a strange land, that they were sleeping far away from home, far from mothers and sisters, and as they dropped the Spring roses of our own sunny clime upon their silent resting-places, it was with the Christian hope that some fair sister in the North, in a like charitable spirit, might not overlook the silent graves of our Southern sons which are scattered among them.”

We need more of this type of story put in the book that are in school to like our people know we have done so thing doing the war that help America da it is today.

Cicero mcgee

I thank the ancestors for the Internet. We are able to get to the TRUTH regarding the United States.

I am grateful for people like you who do the public such a service by telling the history of this great nation, even at its worst moments. This is a fallen world we live in; and Evil has (and still does), its tremendous influence on the horrendous treatment of human beings among themselves.

Thank Goodness that we have been given a ray of Hope for all this hatetred, wickedness, and Evil to be conquered while Peace and Love become victorious.

Thank You – Scott Eastman

The L.A.Times published an illustrated history about the first Decoration day in Sunday’s paper(May 24,2015) page A31, It was a whole page presentation. The illustrations were done by Steven Brodner an “satiric artist and illustrator”. The last paragraph says ” within 50 years, the locals would deny the events of May 1, 1865 had ever taken place. Nonetheless, says Blight (David W. Blight historian)Memorial Day belongs to Charleston”s freed men and Women who “by their labor, their words, their songs and their solemn parade created for themselves, and for us the Independence Day of the Second American Revolution”.

David Blight is an American treasure- this is the type of REAL history that I love to share with my students as a high school teacher- he is helping “set the record straight”! Look to Howard Zinn, another great American hero, to complete the picture… !

What essential history American history, yet how much it is covered up by the dominant culture and taught in a totally biased way…thank you for helping us all learn and remember.

This is so moving and should be taught to our young black men to assure them of our worth.

Thank you Mr. Blight. We see there is way more to Memorial Day than what the mainstream wants us to “remember”.

A remarkable story that needs to become part of Memorial Day — the pain, the celebration and the true beginning.

I felt the same thrill when I discovered Eugene Bullard in a dusty old book left on top of a book case in the NY Public Library. I was doing research for a novel I was writing called “The Color Line” about the Harlem Hellfighters of World War One. Finding out that we could take additional pride in Eugene Bullard, a Black flying ace in World War One, gave me such a swell of pride. So, of course, I had to mention him in my book. Then a couple of years later, the History Channel did a documentary about Black flyers and I watched like a hawk to make sure they mentioned Eugene. He was the first person they talked about! So Google Eugene Bullard and get your prideful smile on today!

Fascinating uncovering hidden and lost history of our peoples depth of courage, passion and unity. Quite the opposite of what history has or has not recorded and we have believed from generation to generation. African Americans are an amazing group of people.

Out standing that the real history is put forth by electronic media. This would not be front page news in your local newspaper. I will be printing this.

Good idea to have the truth in children’s books.

They will never print this in our children’s history books. That’s why we Homeschool. We teach the truth in everything. What an amazing story in history blocked by the elite. As they always say there are two sides to every story, and today we found out the other side! Thank you Mr. Blight for research and for your truth.

I can only imagine the courage it took to stage this first celebration.

And the truth shall set you free. It’s time to honor the contributions of founders of such honorable people. It’s time to have the above story published in children’s history books to give credit where credit is due.

And the truth shall set you free. It’s time that credit be given to the people who started these traditions. All races have the ability and have demonstrated good and wonderful deeds. This story belongs in all children’s history books. It’s time that the descendants of Black, Native Americans, Asians and all the different people of the world be credited for their marvelous contributions to the human race. It’s time that whites (of which I am one) stop taking credit for things we haven’t done and owning up to the not so pretty things we have done.

Once again our black ancestors are pioneers in doing what is right.