By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

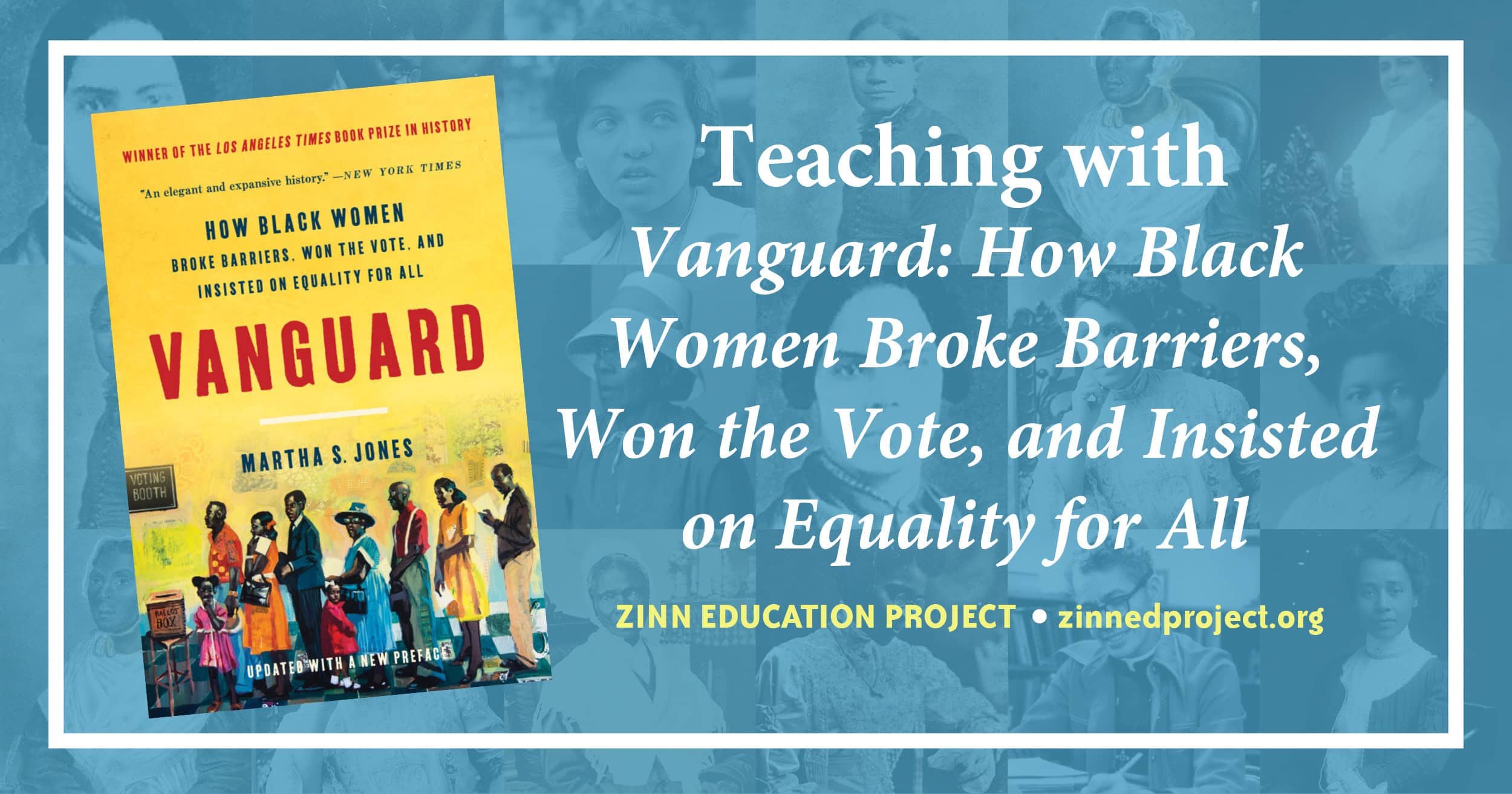

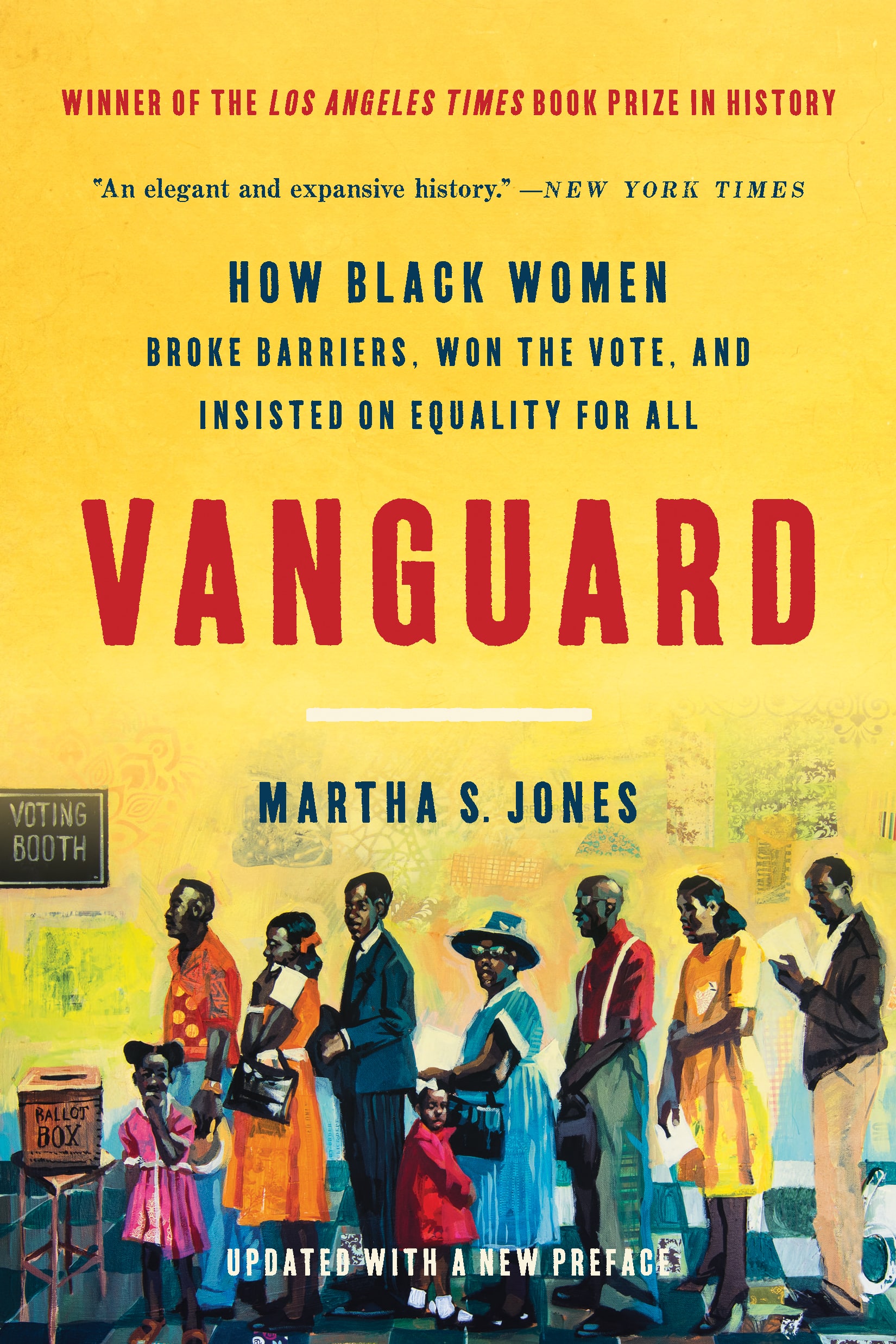

Martha S. Jones’ Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All is a love letter to Black women’s organizing for justice. It includes profiles of more than two dozen women.

Some of these women may already be in our curriculum — Ida B. Wells and Fannie Lou Hamer, for example — but many more are likely not.

Some of these women may already be in our curriculum — Ida B. Wells and Fannie Lou Hamer, for example — but many more are likely not.

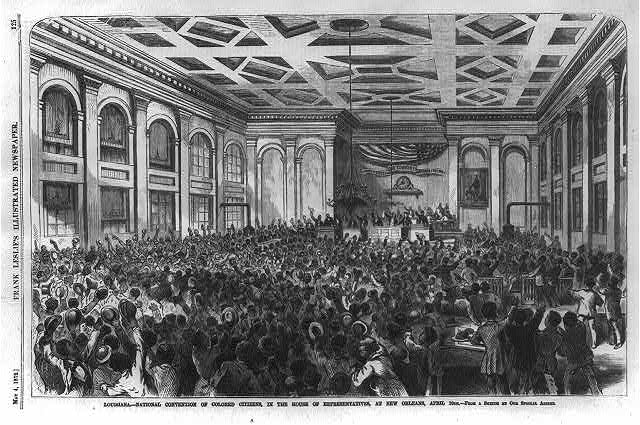

There is Jarena Lee, who transformed expectations around women’s role in the church by becoming a traveling AME preacher in the early 19th century; Hester Lane a formerly enslaved woman who started a successful home decorating business in New York City, rising to prominence in the American Anti-Slavery Society; Mary Ann Shadd, publisher of the Provincial Weekly, a newspaper that advocated against slavery and for the right of women to speak and write in public, own and control property, and work.

In this lesson, students read short excerpts from Jones’ book to learn about these and other women, share what they learned with each other, and use what they’ve gathered to analyze Jones’ provocative title — in what sense were these women a “vanguard” and why?

Where from Here

There are a lot of directions you might take this activity. In a recent workshop with teachers, the mixer was followed by each participant writing a “Write That I” poem (an idea borrowed from Linda Christensen) from the perspective of the woman they learned about. With students, you might give them the option to choose any one of the women to focus their poem on — and to learn more about them in the process. In that same workshop, we also placed Vanguard into conversation with the Combahee River Collective statement of 1977, in which a group of Black lesbian socialist feminists wrote, “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

The Combahee statement itself included echoes of the Black communist Claudia Jones’ 1949 essay, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman,” which asserted that Black women were potential source sources of “heightened political consciousness,” because “Negro women — as workers, as Negroes, and as women — are the most oppressed stratum of the whole population.” The point here is that there is a long history of scholars and activists thinking about how the experiences and social position of Black women shape — or should shape — struggles for justice, and students will make more of Jones’ text when they can see it as part of this ongoing conversation.

Share Your Feedback

Share a story about using this lesson and we’ll send you a copy of Vanguard in appreciation. Write here.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn