“I learned there was an era of Black power that I didn’t even know existed,” Sean wrote. “That there was a MAJOR Black power movement in the 1860s and 1870s, is so exciting to me!” Joel added. “As a Black student, I’m really happy to be learning about it . . . because everyone thinks that it was only in the 1960s when there was a powerful Black rights movement.”

I had asked my African American history students at Philadelphia’s Central High School to summarize what they had learned from our unit on Reconstruction and whether they thought it was important for students to know about this era and why. The answers I received were a testament to how empowering learning about Reconstruction can be for students — in a way that emphasizes the dramatic struggles and successes of the era.

Layla wrote, “It’s important for students to learn about this era because it’s not as simple as slavery being abolished and then Jim Crow laws were implemented — there was a time period in between. This period teaches us that progress that is made can be undone.” And Tevin added that “learning about Reconstruction teaches us that if people come together, they can bring forth major political reforms — even changes to the Constitution.”

Library of Congress: Five Black women who served as officers of the Women’s League in Newport, Rhode Island (circa 1899).

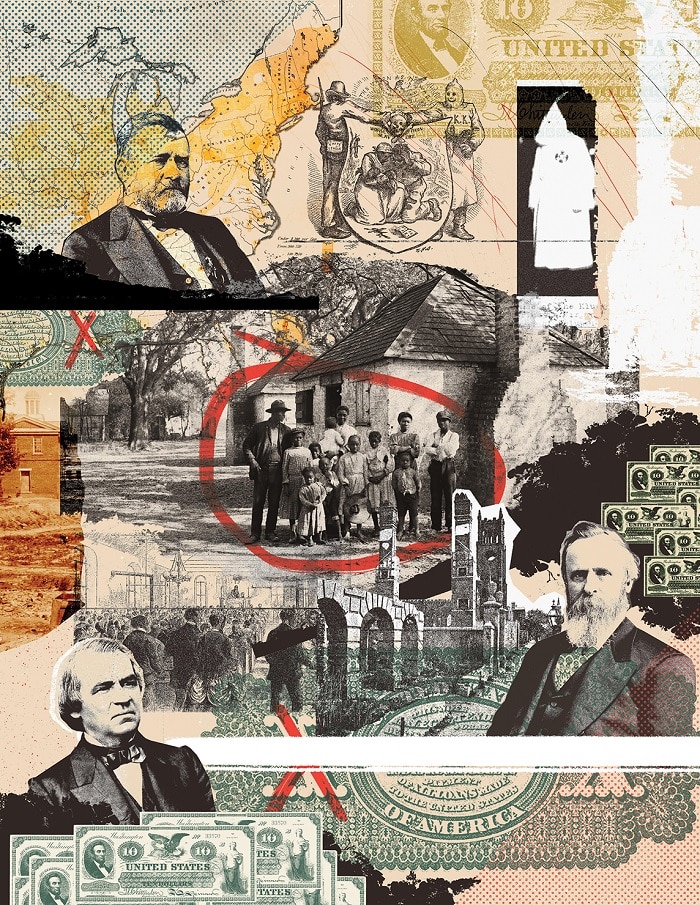

The conclusions my students came to about the Reconstruction era were conclusions that many drew at the time and many historians have drawn since. Ironically, it was racist journalist James Shepherd Pike who captured the revolutionary dimension of Radical Reconstruction when, writing in 1873 about the Black-majority legislature in South Carolina, he saw “the spectacle of a society suddenly turned bottom side up.” Pike was horrified. Historian Lerone Bennett Jr. analyzed Pike’s reaction in his book Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction, 1867–1877: “Nothing in Pike’s past life had prepared him for such a turnabout . . . Black people in charge, running things, and white people, ‘cowed and demoralized’.”

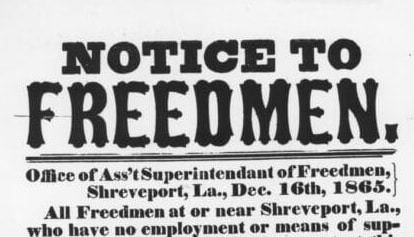

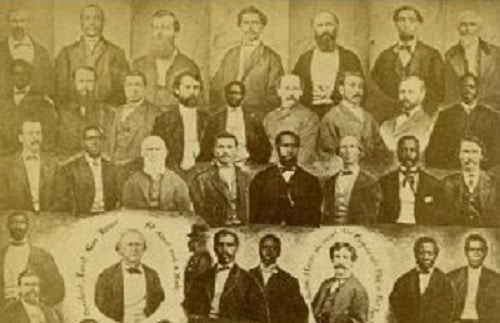

Indeed, the period commonly referred to as Radical Reconstruction was precisely one of those rare moments where poor people grasped the levers of power. Textbooks often focus on the few Black people who made it to the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives. Although these are certainly some of the most dramatic symbols of the revolution that swept through the South, it’s the smaller local positions — Black jurors, judges, tax assessors, sheriffs, county commissioners, school board members — that give a sense of the drastic ways Radical Reconstruction transformed the day-to-day lives of most Black people. As historian Steven Hahn writes, “Never before — and rarely again — in the history of the United States would such a substantial section of the working class have the opportunity to contest the power of their superiors in the formal institutions of governance that affected their lives most directly. It proved to be a turbulent and telling experiment in the meaning of democracy.”

And beyond those who gained official titles, the actions of everyday people — demanding better treatment on the streets and on the plantations, organizing self-defense against reactionary whites, protecting families and allies, protesting for better treatment — reveal the many attempts to make society anew and prevent the old racist relations from returning.

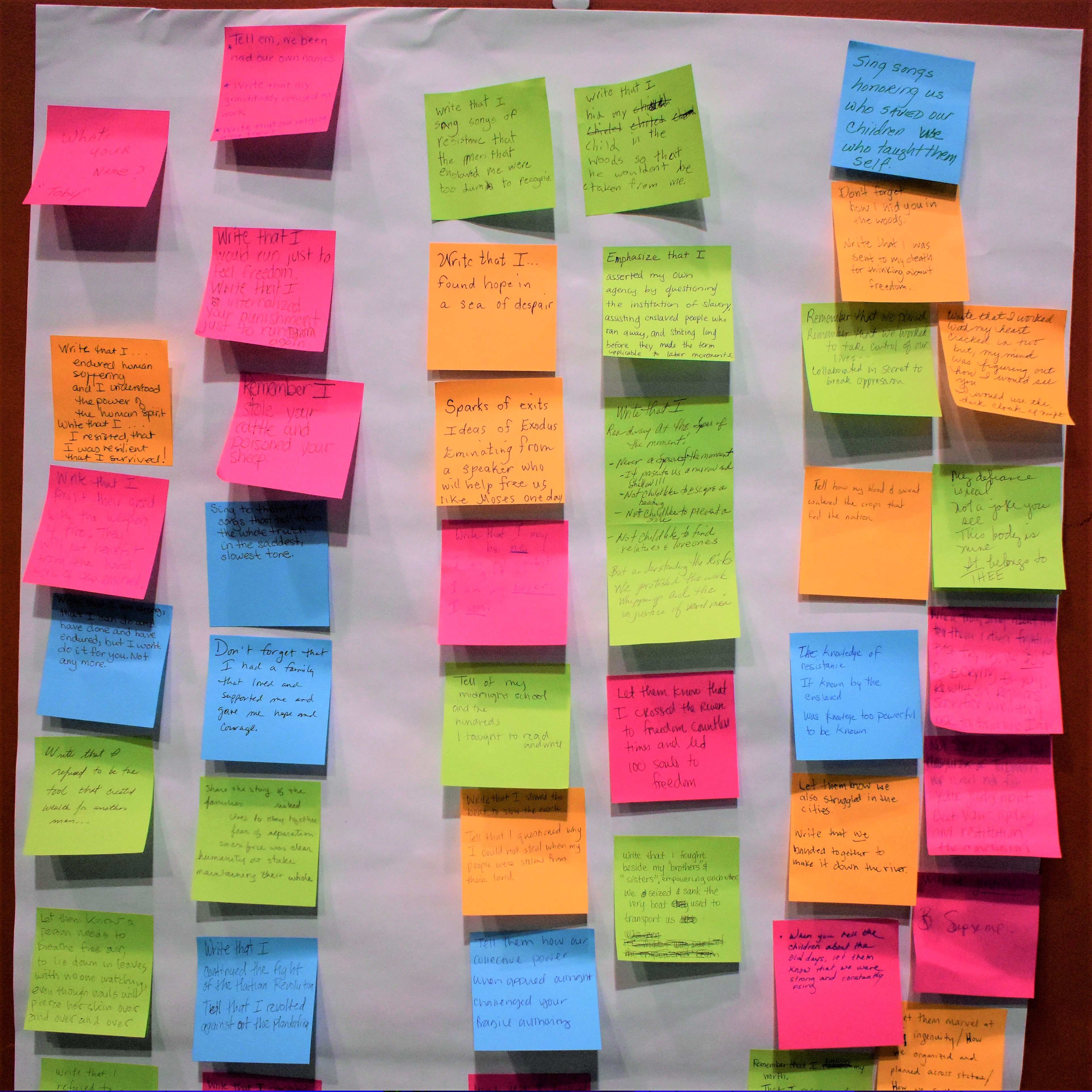

Although this period is paralleled by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and ’70s in the sheer numbers and boldness of Black people fighting racist practices and contesting for power, there are far fewer resources that give students — especially K–12 students — a sense of the revolutionary upheaval that swept the country during the late 1860s and ’70s. To address this, I created two lessons that help students understand, imagine, and celebrate this moment as the first era of Black power in the United States.

Continue reading this article with the lessons on teaching the revolutionary aspects of Reconstruction at Rethinking Schools.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn