By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

When I wrote this introduction in the summer of 2020, there had already been more than five weeks of nightly Black Lives Matter demonstrations in my city of Portland, Oregon, sparked by the brutal murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. This exhilaratingly extended period of nationwide protest can be attributed to many factors: the steady drumbeat of new revelations of equally awful examples (Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain) of state-sanctioned murder of Black people; widespread teargassing, pepper-spraying, use of “nonlethal” projectiles, and beating of protestors by police in dozens of cities; and the coronavirus pandemic, which has disproportionately infected and killed Black people in terrifying numbers, and has also created disruptions to daily life that, paradoxically, opened up space for rallies, marches, organizing. More than anything, this moment feels like a reckoning with the United States’ past, with its long history of white supremacist violence, from slavery to George Floyd, and equally long history of Black resistance.

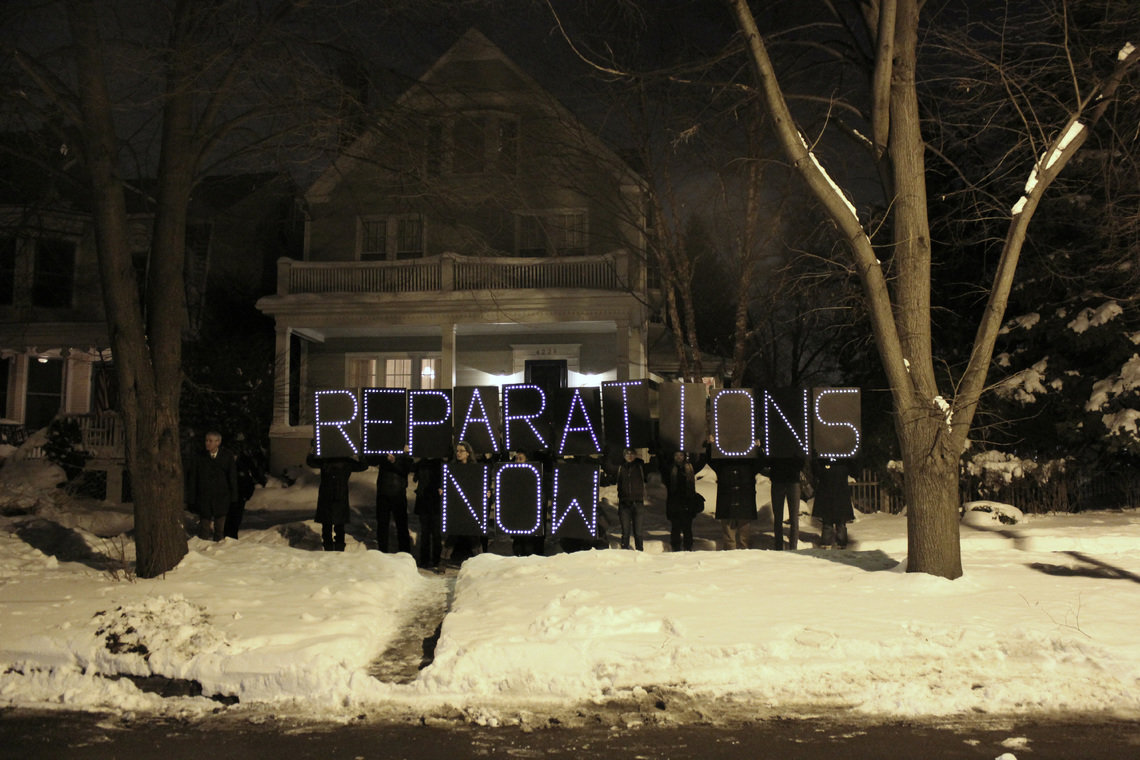

To reckon means to establish by counting or calculation. What would it mean to really reckon with the historical costs of white supremacy on Black life? What would it mean to count up all the violence, theft, harm, and injustice inflicted on Black people in the last 400+ years of white settlement of this land? It would mean establishing what actually happened, not what our historical fables and corporate textbooks peddle. More critically, it would be a first step in calculating what is owed.

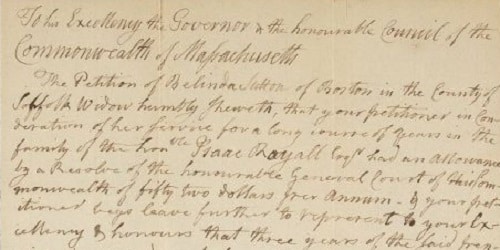

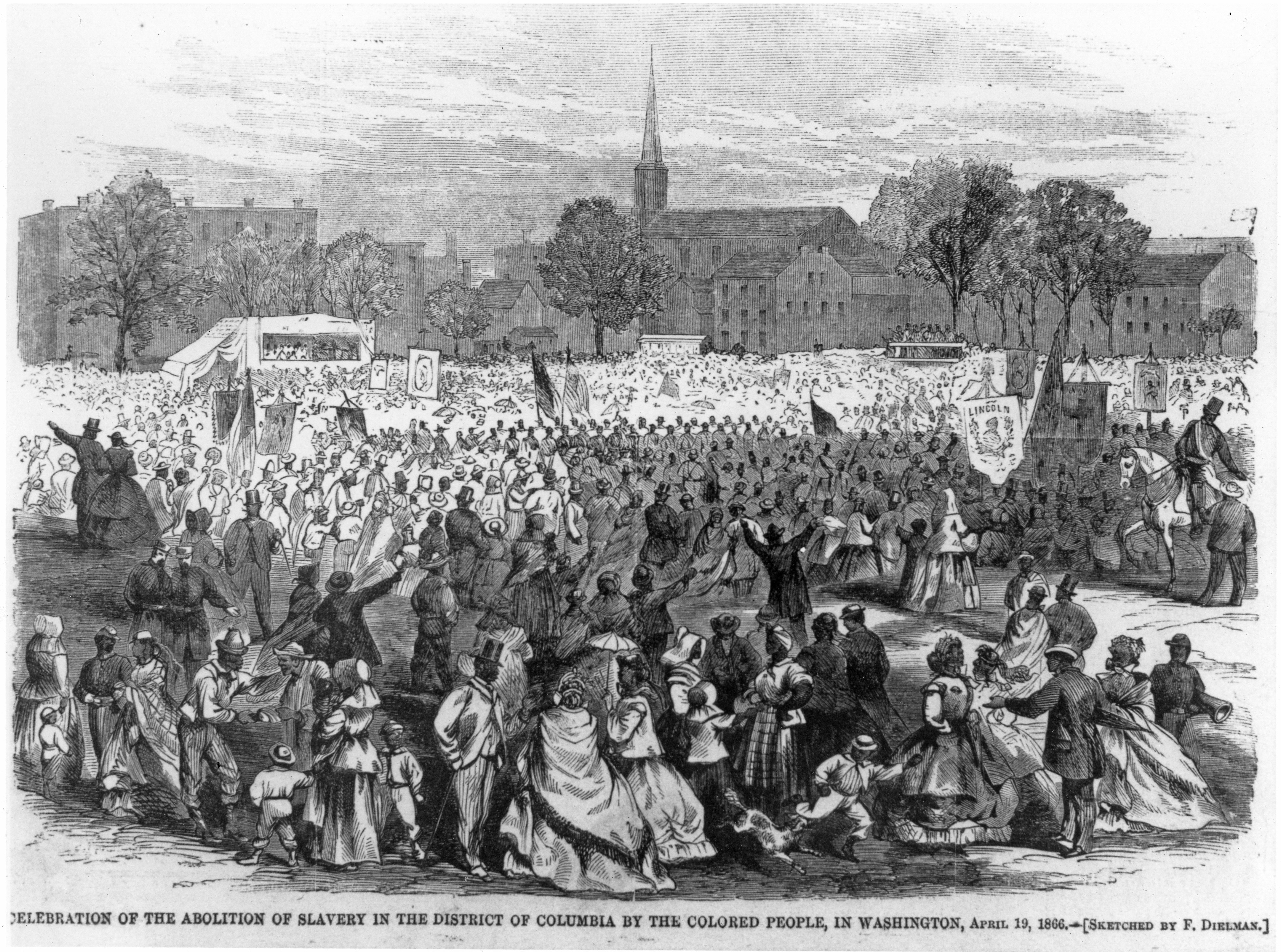

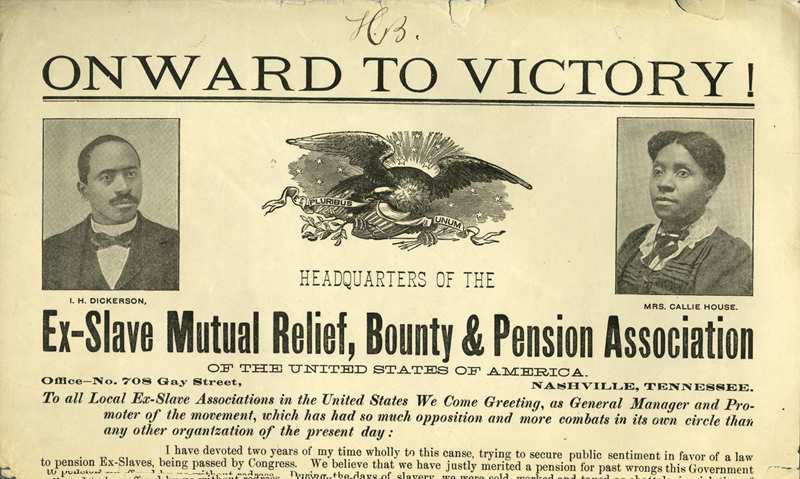

Reparations for Black people in the United States is not a new idea. Before the Civil War was even over, Special Field Order No. 15 was issued to confiscate land from Confederate land owners to be divided among newly freedpeople “to establish a peaceable agricultural settlement.” Activist Callie House called on Congress in the late-19th and early 20th-century to provide formerly enslaved people like her, and 4 million others, modest “pensions.” In the 1950s, Queen Mother Moore founded the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, where she started investigating the idea of reparations. When the Black Panthers issued their 10-point program in 1966, they demanded compensation for stolen wages and genocide: “the payment in currency that will be distributed to our many communities.”

In spite of this rich genealogy, reparations are nowhere in the textbooks my school district has adopted to help me teach young people in the United States about their past. Looking up the word “reparations” in the three recently published textbooks on my shelf is to find it absent altogether, or only in reference to the end of World War I or U.S. payments to Japanese Americans (incarcerated in concentration camps during World War II) in the 1980s.

The message of the corporate textbook committees is clear: Reparations for Black people is so outlandish an idea as to not even merit mention.

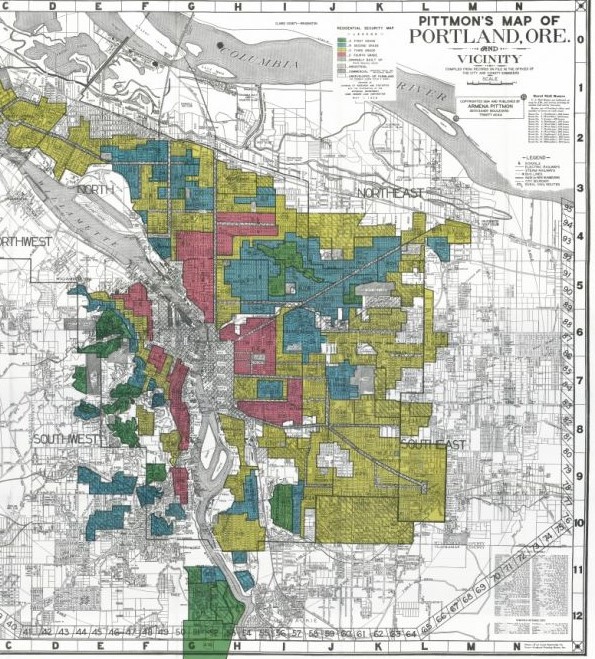

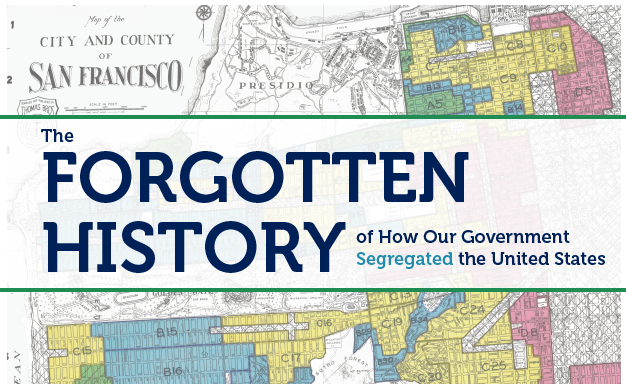

But not so outlandish anymore. In 2014, Ta-Nehisi Coates published his gorgeous essay, “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic, which persuasively and painstakingly laid out how 20th-century structural racism stole Black people’s wealth just as surely as 19th-century slavery stole their bodies, labor, and knowledge. Also in 2015, activists in Chicago won a long-fought battle to win reparations for victims of Jon Burge and the Chicago Police Department’s campaign of torture and won “the Burge torture curriculum,” a requirement that the story of the torture and the activists who fought it be taught to Chicago students.

In 2019, Georgetown University students approved a student “Reconciliation Contribution” fee to benefit descendants of 272 slaves sold by the school in the 19th century.

In 2019, for the first time in more than a decade, Congress held hearings on the decades-old bill, HR 40, a modest effort to simply establish a committee to develop reparative proposals. 2019 was also the first time in U.S. history that presidential contenders — in the Democratic primaries were expected to have a “reparations position,” so common was it for them to be asked about it. Long overdue, reparations have entered the mainstream. It’s surely time then, for it to enter our classrooms and curriculum too.

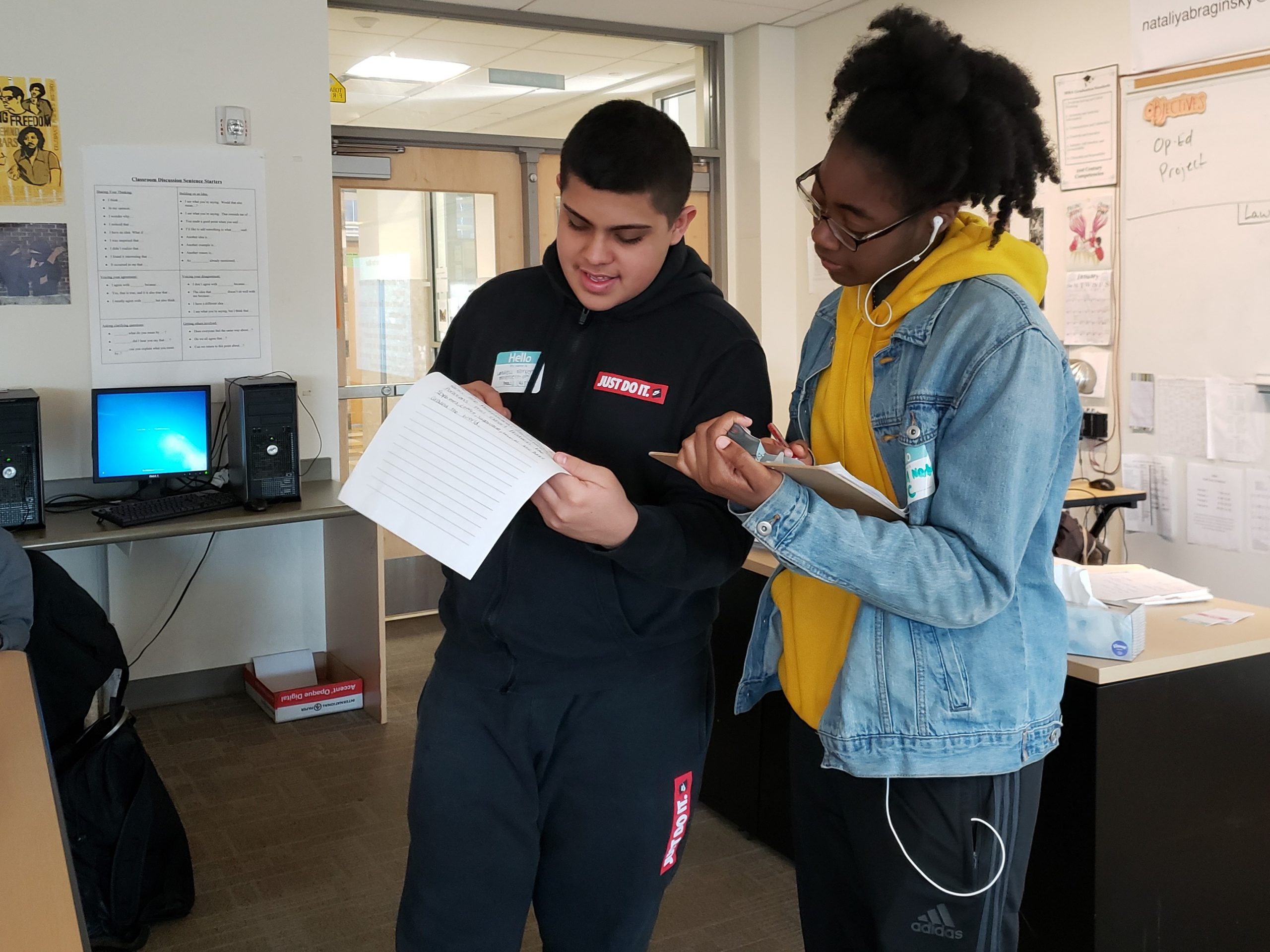

The premise of this lesson is that Congress has finally taken on the task of reparations legislation. But what Congress offers is extraordinarily weak sauce. Students take on the role of activist-experts working in one of the following domains of racial justice: Education, voting, housing, labor, health care, or criminal punishment. They talk back to Congress’ flimsy legislation and design a more robust alternative. In crafting amendments and additions to the bill, students must decide what form the reparations should take, how much is due, and argue which needs are the most immediate, pressing, and fundamental. As racial justice activists, students are all on the “same side” in this role play, but they come to the discussion with different expertise and priorities. As they struggle to design reparative policies that will address the needs of all the groups present (and thereby garner support in the mock congressional hearing), their discussions reveal the deep interconnectedness of different forms of oppression and how critical it is to untangle the symptoms of a disease from their underlying causes.

Classroom Story

When teaching Reconstruction to my middle school students, I have my students go through the process of designing a Reparations bill by participating in extensive group discussions and utilizing a digital workspace. It has worked out well, and my administrator mentions it often as an example of excellent practice. Having the students examine what they think should have happened before they learn about what actually happened has been a fantastic experience.

We engaged in a series of small debates and I have never had more successful conversations in my classes. I would suggest offering different ways for your students to participate (we typed responses and talked out loud), while remembering that listening is a completely valid way of engaging. Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill followed by the lesson Reconstructing The South: What Really Happened is a powerful sequence of learning. I couldn’t recommend them more and I am grateful to have them as part of my curriculum.

Love the resource! But I wonder if it wouldn’t be more constructive to ask the question, “are reparations necessary?” Then it would be open for the students to learn the history and come to a conclusion themselves instead of being told that indeed they are. Imagine how rich of experience it would be for students to research and construct an argument in regard to that question The products they could create would also be authentic and could be used to enact real change.

The products they could create would also be authentic and could be used to enact real change.