“I don’t know what to write.”

We were several days into our writing unit on personal narratives and Natalie was staring at a blank piece of paper. I went through the questions I ask students to try to help them generate ideas. Pets? Family celebrations? Learning to do something new? Memorable trips you have taken?

“I visit my grandparents in Idaho every summer.”

That was the spark.

Natalie wrote about being Nez Percé and Lakota, her dress and shawl that her grandmother sewed for her, and the dances that bring her joy.

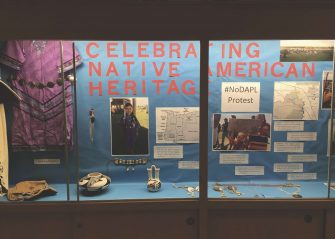

I shared her story with her parents at conferences and they were moved. Our school has a parent equity committee and throughout the year they create displays in the hallway cases. The week after conferences, I was pleasantly surprised that Natalie’s parents had made a display case in the hall of the school to celebrate Native American Heritage. Included in it was a photograph of Natalie in the dress from her story, jewelry and pots, and a map of Indigenous land. The display also included information about the Dakota Access Pipeline protest at Standing Rock.

One day our class stopped at the display and I read everything to them. That’s when the questions began and our climate justice study began in earnest.

“Why are they putting the pipeline there?” “How many pipelines are there?” “How many spills are there?”

I started by looking up a map of existing pipelines in the United States. I printed it out and hung it on the board. The crisscross of lines was so dense in the Southern states we couldn’t make out individual lines. Students gasped.

Then I looked up oil spills in the United States and found Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration data on the Department of Transportation website. I printed out their list of Pipeline Failure Investigation Reports and it was more than six pages in a tiny font of pipeline failures spanning from 2003 to 2013. As I flipped page after page of spills, their shock grew.

Then I looked up oil spills in the United States and found Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration data on the Department of Transportation website. I printed out their list of Pipeline Failure Investigation Reports and it was more than six pages in a tiny font of pipeline failures spanning from 2003 to 2013. As I flipped page after page of spills, their shock grew.

“That is so many!” “I thought it was just a couple pages but it just keeps on going!” “Why do we put in more pipelines if there are so many spills?” “What happens to the water and animals that live there?”

I could see that my students were hungry to learn more but I am no expert. There is very little curriculum on climate change and I had to be willing to learn alongside my students. I wanted my students to start to understand the scope of change needed to deal with climate change as well as their own ability to push for that change. Fortunately, I had colleagues who felt just as passionately that our students deserve to explore their questions and concerns about our planet. We met frequently to plan and share resources in order to bring this learning to life in our classrooms.

Fossil Fuels

I started with fossil fuels.

I read Molly Bang’s Buried Sunlight to the students, which explains how fossil fuels are formed and the many ways we use them. I read aloud books introducing the idea of the commons and our shared earth and resources, and I read aloud about greenhouse gases, global warming, and climate change. I created a wall chart by first drawing simple illustrations of the formation of fossil fuels and the greenhouse effect and transcribed student responses to questions I asked that included “How are fossil fuels formed? What are they made of? What are greenhouse gases? What makes carbon dioxide? Methane? Nitrous oxide?”

I read Molly Bang’s Buried Sunlight to the students, which explains how fossil fuels are formed and the many ways we use them. I read aloud books introducing the idea of the commons and our shared earth and resources, and I read aloud about greenhouse gases, global warming, and climate change. I created a wall chart by first drawing simple illustrations of the formation of fossil fuels and the greenhouse effect and transcribed student responses to questions I asked that included “How are fossil fuels formed? What are they made of? What are greenhouse gases? What makes carbon dioxide? Methane? Nitrous oxide?”

Next, I wanted students to explore the difference between individual actions versus ending our dependence on fossil fuels. I wanted them to understand our country’s reliance on fossil fuels and that we would need to make big systemic changes in how we get our energy in order to break free from that dependence. Together we made a list of all the ways we use fossil fuels for energy. Students saw that we rely on oil and gas for most of our electricity and vehicle transportation needs.

“If we all shut off the lights when we leave a room or ride our bikes more, is that going to solve our problems with pipeline spills or drilling for more oil? Is that enough to end our dependence on gas and oil?” I asked.

“No!” they responded. “We still have all the cars!” “And we heat our houses with fossil fuels.” “And our refrigerators and TVs.”

I then posed other questions to them: “Could we stop using all fossil fuels tomorrow and still turn on our lights and heat our house? Do we have other ways to create electricity?” . . . Continue to read in full.

Rachel Hanes teaches 2nd grade at Glencoe Elementary in Portland, Oregon. She is a member of the Portland Public Schools Climate Justice Committee and is active in the Portland Association of Teachers.

This teaching activity is from the Winter 2020 issue of Rethinking Schools. Subscribe to the Rethinking Schools magazine today.

This teaching activity is from the Winter 2020 issue of Rethinking Schools. Subscribe to the Rethinking Schools magazine today.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn