The United Nations has declared this the Decade of Peace. The troubling irony is that teaching for peace must begin with a study of war. Unless we look carefully at the dynamics of war and come to grips with the root causes of global conflicts, we have no way to convincingly propose solutions-no way to imagine peace.

The United Nations has declared this the Decade of Peace. The troubling irony is that teaching for peace must begin with a study of war. Unless we look carefully at the dynamics of war and come to grips with the root causes of global conflicts, we have no way to convincingly propose solutions-no way to imagine peace.

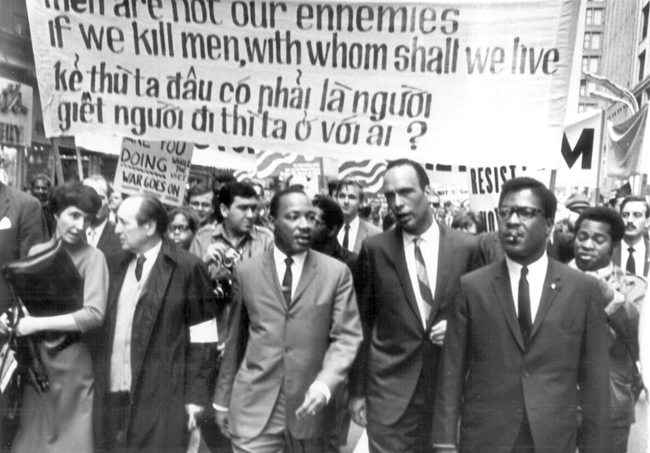

Sadly, when it comes to probing the root causes of the Vietnam War, not a single major U.S. history text glances back beyond the 1950s. Why was the U.S. involved in Vietnam?

As James Loewen points out in Lies My Teacher Told Me, his critique of 12 best-selling high school history texts, “Most textbooks simply dodge the issue. Here is a representative analysis, from American Adventures: Later in the 1950s, war broke out in South Vietnam. This time the United States gave aid to the South Vietnamese government.’ War broke out’ — what could be simpler!”

When teachers pattern our curricula after these kinds of nonexplanatory explanations, we mystify the origins not just of the war in Vietnam, but of everything we teach. Students need to learn to distinguish explanations from descriptions, like “war broke out,” or “chaos erupted.”

Thinking about social events as having concrete causes, constantly asking “Why?” and “In whose interests?” need to become critical habits of the mind for us and for our students. It’s only through developing the tools of deep questioning that students can attempt to make sense of today’s global conflicts. However, especially when teaching complicated events like the war in Vietnam, bypassing explanation in favor of description can be seductive. After all, there’s so much stuff about the war in Vietnam: so many films; so many novels, short stories, and poetry; so many veterans who can come in and speak to the class. These are all vital resources, but unless built on a foundation of causes for the war, using these can be more voyeuristic than educational.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn