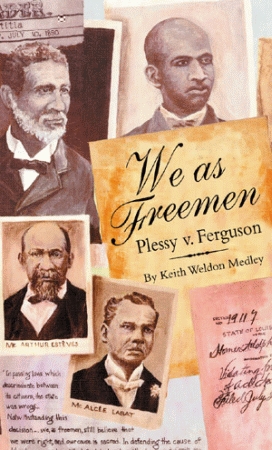

Below is an excerpt from an article by Keith W. Medley (author of We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson) about the organizing by the Comité des Citoyens that led to Plessy v. Ferguson. It is a powerful story of organizing, fundraising, the use of the media, legal strategies, and more.

Regardless of the outcome of the court case, it is an important example of the strategic efforts by African Americans to challenge state and nationally sponsored white supremacy.

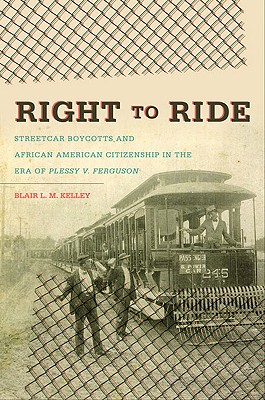

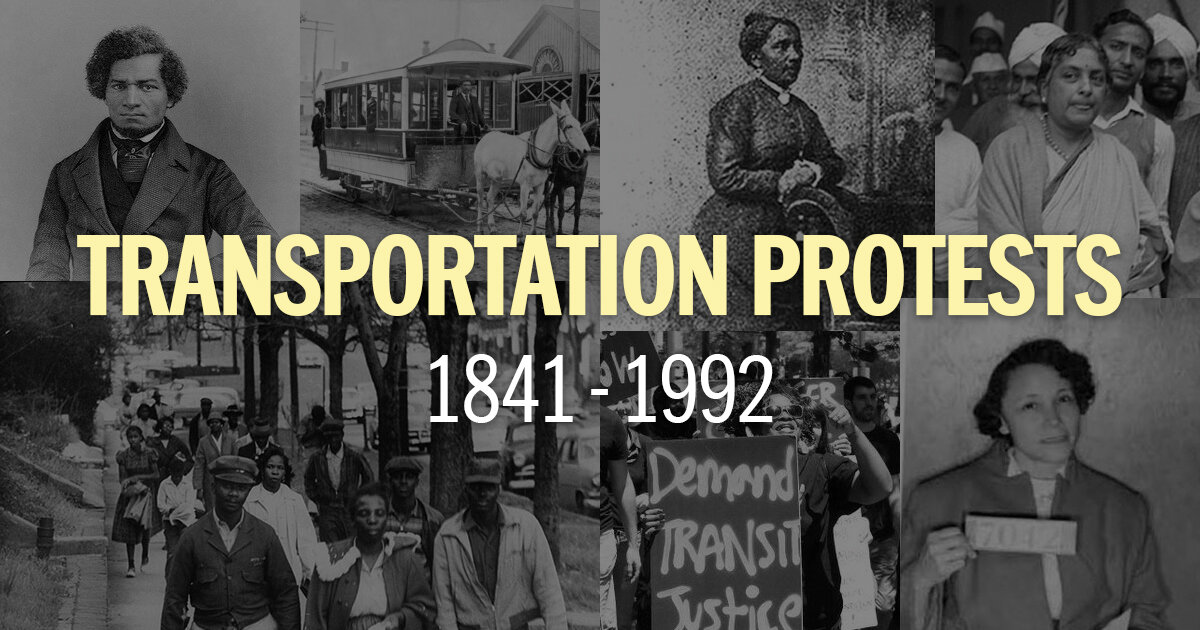

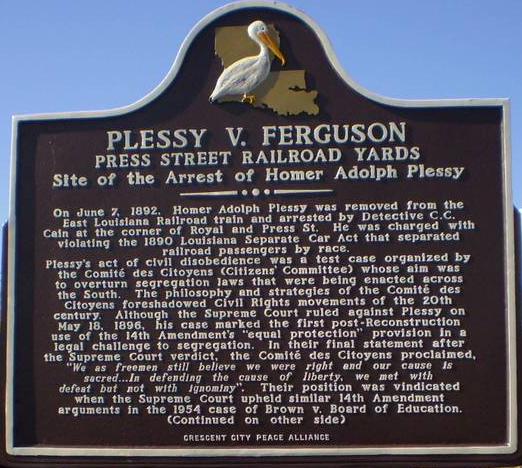

Louisiana Legislature’s Separate Car Act in 1890 decreed “equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races” on Louisiana railway cars. It was the passage of this bill that finally launched Homer Plessy into history. The fight involved a Black newspaper, The Crusader, the six remaining Black state senators and ultimately the Comité des Citoyens, which coalesced around The Crusader.

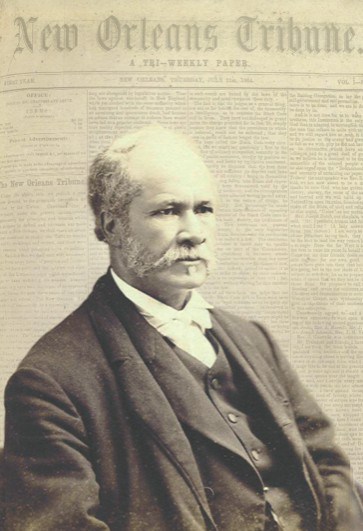

The Crusader was a formidable enemy. A weekly founded in 1889 by the attorney Louis Martinet to combat the increasingly virulent racism of other New Orleans papers, it called itself “spicy, progressive, liberal, stalwart, fearless,” and stood for “A Free Vote and Fair Count, Free Schools, Fair Wages, Justice and Equal rights.”

The Crusader’s star contributor was Rodolphe Desdunes. The son of a Cuban mother and a Haitian father, Desdunes worked as a customs agent by day and, with smoking pen, scribbled polemical columns by night. Hundreds of his articles, still preserved in the archives of Xavier University in New Orleans, offer a window into the desperate fight to keep civil rights from slipping away.

“Colored people have largely patronized the railroads heretofore,” Desdunes wrote on July 19, 1890. “They can withdraw the patronage from these corporations and travel only by necessity.” He proposed a boycott, not unlike the one launched in Montgomery, Alabama, 70 years later.

The 1890s were not a good time to exercise civil disobedience in the American South, or to get on the wrong side of a mob, whether you were Black or not. The year 1892 alone produced 226 mob murders, mostly of Black men, the highest number in the recorded history of lynchings. In New Orleans, on March 14, 1891, a newspaper editor and a prominent attorney led a crowd of several thousand to Parish Prison. Angry over the acquittal of Italian immigrants accused of the killing of police chief David Hennessy, they broke in, hunted down a group of 11 Italians, shot them, then hanged some from streetlamps and shot them again. [See the young adult novel Alligator Bayou for more on this story.]

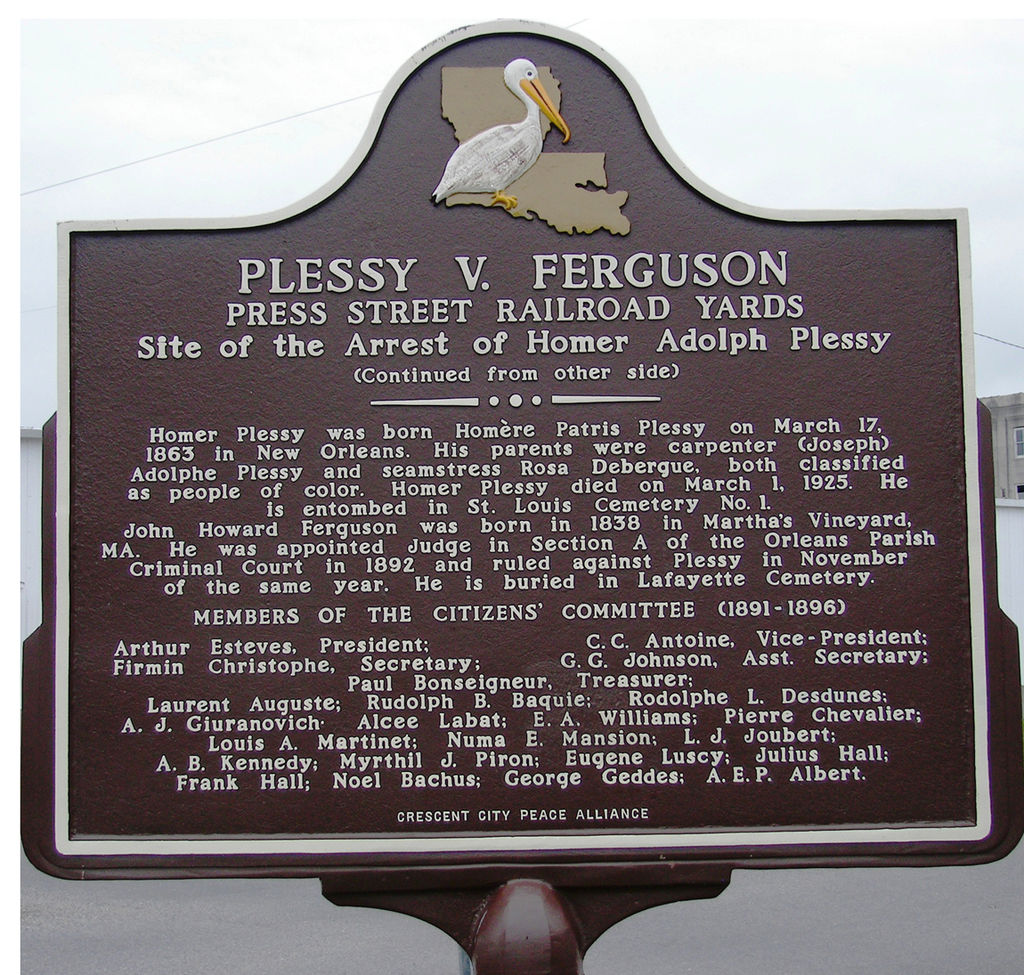

To combat what became known as the “Jim Crow car law,” The Crusader and the Comité des Citoyens acquired a small but influential membership. It involved C. C. Antoine, a former officer in the Union Army, who had served four years (1873-77) as Louisiana’s lieutenant governor, and wealthy philanthropist Aristide Mary, who had financed lawsuits against other resegregated establishments.

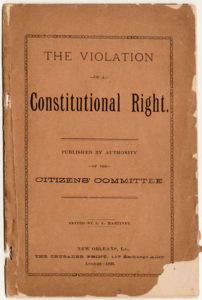

The Comité also included sail manufacturer Aruthur Estèves, who became its president. To fight the Jim Crow car law, it was prepared to solicit funds not only from benevolent, social and religious societies in town but from former abolitionists in such faraway cities as Washington, D.C., Chicago and San Francisco. About $3,000 was quickly raised to launch two test cases: one to challenge the legal segregation of trains on interstate routes and one to challenge segregation on conveyances within the state. The aim: to “seek redemption” from the Supreme Court of the United States. “We find this the only means left to us,” a Comité statement concluded. “We must have recourse to it, or sink into a state of helpless inferiority.”

The Comité also included sail manufacturer Aruthur Estèves, who became its president. To fight the Jim Crow car law, it was prepared to solicit funds not only from benevolent, social and religious societies in town but from former abolitionists in such faraway cities as Washington, D.C., Chicago and San Francisco. About $3,000 was quickly raised to launch two test cases: one to challenge the legal segregation of trains on interstate routes and one to challenge segregation on conveyances within the state. The aim: to “seek redemption” from the Supreme Court of the United States. “We find this the only means left to us,” a Comité statement concluded. “We must have recourse to it, or sink into a state of helpless inferiority.”

It was a forlorn hope, but not as forlorn as it would become in the slow process of going through the legal system. For one thing, on the face of it, if you gave any thought to the intent of the men who wrote the 14th Amendment, the Separate Car Act seemed a clear violation of the constitutional rights of the Black citizens of Louisiana. But public opinion in the North had changed rapidly, and so, in the years after 1877 had the makeup of the Supreme Court, which lost its reasonable mix of justices sympathetic to the subject of civil rights.

Some railroad companies initially had been against the bill. It was going to cost money to build and run extra cars — for the bill implied that if a half-empty “white” car was waiting, and even if only one Black passenger showed up, he or she would have to have a whole separate-but-equal vehicle made available. In a city that had for so long seen so much racial mixing, railway conductors would now have to decide who was white and who was Black — a touchy business, especially since some wives and husbands would not be allowed to ride together.

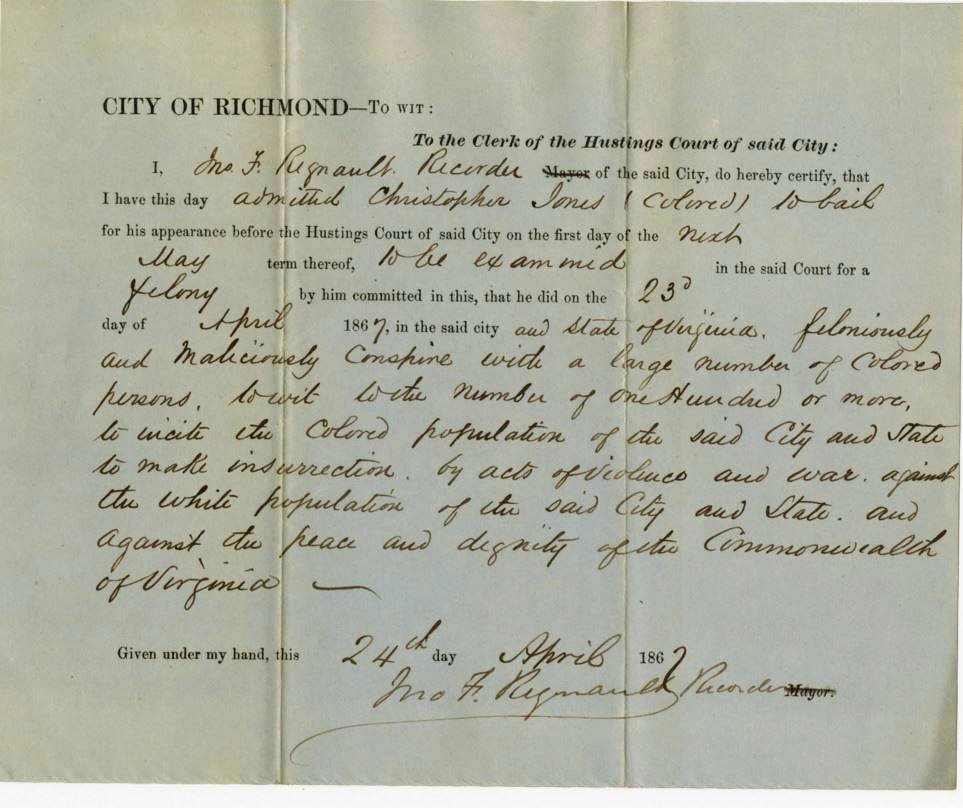

One of the reasons that Homer Plessy was picked for the job [of creating a test case to fight the law] was that he had fair skin. Had it been left to chance, he probably could have ridden the train in the “whites only” section unnoticed. But by prearrangement between the Comité and the East Louisiana Railroad, everything was ready for him when he came.

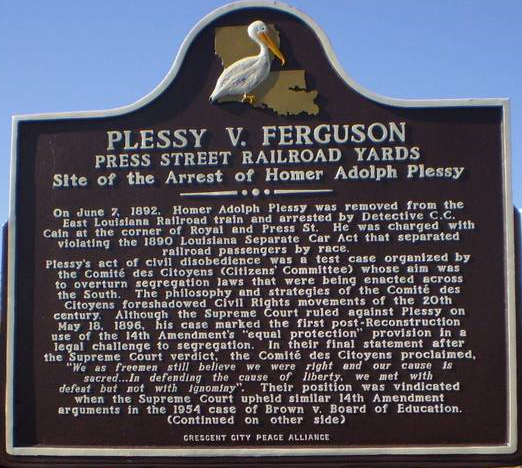

On June 7, 1892, Plessy strolled to the Press Street depot, which included a restaurant and a combination waiting room and ticket office (both still open to him), bought a first-class ticket and, ignoring the new “Colored Only” sign, sat down in the coach reserved for whites. It was to depart at 4:15 P.M., cross a bridge spanning Lake Pontchartrain and pass through Abita Springs for a two-hour run to Covington.

Hardly had the train started moving when conductor J. J. Dowling approached Plessy. “Are you a colored man?” he asked. “Yes,” answered Plessy. “Then you will have to retire to the colored car,” said Dowling. Plessy stated that he had paid for his ticket and intended to ride to Covington. Dowling signaled the engineer to stop. A private detective, Captain Chris Cain, hired by the Comité, came aboard and warned Plessy: “If you are colored you should go into the car set apart for your race. The law is plain and must be obeyed.”

When Plessy again refused, he was taken a half-mile down to Elysian Fields Avenue for booking at the Fifth Precinct Station. Members of the Comité met him, and a judge released him on temporary bail. The next day a story in a New Orleans daily described Plessy as a “snuff-colored descendant of Ham.” After a hearing, Comité member Paul Bonseigneur plunked down a $500 bond (raised by putting his own house in hock) to guarantee Plessy’s appearance for trial. Plessy was 30 years old. The future of constitutional rights for Blacks in America would ride on his day in court.

© Keith W. Medley. Reprinted here with permission from the author. Excerpted from an article he wrote for the Smithsonian Magazine and later developed into the book We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson.

© Keith W. Medley. Reprinted here with permission from the author. Excerpted from an article he wrote for the Smithsonian Magazine and later developed into the book We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson.

Related Resources

Plessy v. Ferguson court ruling from Our Documents website.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn