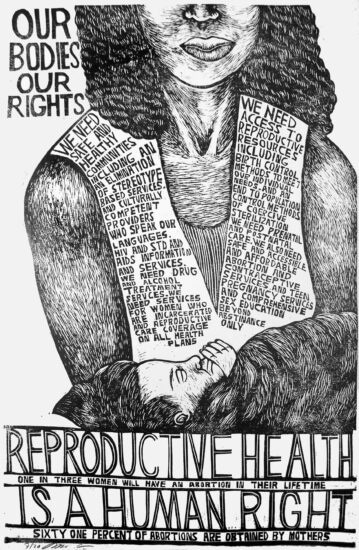

Artwork by Rommy Torrico

Content warning: This document collection includes mention of sexual violence.

By Wesley Hogan

Whatever a person’s stance today on abortion and contraception, it is often quite a distance from people’s approaches to abortion and contraception in earlier eras of U.S. history. Indigenous people and European colonists alike were clear that for free people, early abortion was legal and morally neutral through the time of “quickening,” or the first movement of the fetus (usually in the fourth month of a nine-month pregnancy). Since enslaved women were treated as property, they did not have legal right to their own body. Enslavers often punished them for using abortifacients, or a substance that induced the end of a pregnancy, because it deprived enslavers of more people-as-property. The idea of the rights of the “unborn” did not emerge until the 20th century.

While it is clear that agreed-upon community values on abortion and birth control have changed over time and place, these documents can help Americans today sort through these historic shifts, and decide for themselves.

Pre-Colonial and Colonial Eras

For many years, the oldest known human inhabitants of the continent were thought to date to 14,000 years ago. A claim in 2021 that human footprints in the New Mexican mud dated to 21,000-23,000 years ago has recently been corroborated by a team of researchers at the US Geological Survey and UC-Berkeley. So what about the earliest and longest-known inhabitants of North America — how did Indigenous nations approach abortion care? At the time of contact, somewhere between 8 and 18 million people lived north of modern-day Mexico. For at least 16,000 years prior to European colonization, collectively these Indigenous Americans successfully reproduced over 6,400 generations of human beings. While each North American Indigenous nation approached reproductive care in unique ways, below students can examine approaches by two, the Haudenosaunee (ho-den-oh-show-knee), spread out across what is today upstate New York, and the Cherokee, covering large parts of the southern Appalachian ridge in today’s North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia.

The Puritans brought English law on abortion care to Massachusetts, where it was both morally neutral and legal until quickening. They changed much of England’s legal system when they established their new community as a “city upon a hill” a new model to humans everywhere, but kept English law’s approach to abortion care as a woman’s issue, part of Puritan family life. Women could choose when and if they would become mothers — whether for the first time or the fifth time — under English Common Law.

In 1656, Elizabeth Keye successfully sued for her freedom (her mother was an enslaved Angolan owned by her father a white, property-owning Englishman and member of the Virginia legislature). Fewer than 150 women of African descent were resident (both free and enslaved) in the Virginia Colony at the time of the suit; 15,000 English settlers populated the colony. Keye won her suit based on centuries of Anglo-European legal custom of both patrilineal descent and the traditions of Christianity. However, in 1662, the Virginia Legislature reconsidered, overturning centuries of English Common Law: “All children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.” With this gigantic change from English Common Law, the Virginia legislature racialized reproduction. Only white women could produce white children. Enslaved Black women’s children were all enslaved, even if their biological father was white. A century later, the United States expanded this law for the entire country — enslaved Black women reproduced enslaved children, white women reproduced white children. The condition of the mother, not the father, determined a child’s legal fate. Enslaved African American women did not have body autonomy, that is, they were not legally entitled to determine what happened with their reproduction. They were not allowed to use either contraception or abortion. Instead, the person enslaving them got to decide this. It was not until the Civil War ended that now-freed women could legally determine their own reproductive lives.

People living in Colonial America understood pregnancy differently than today. Midwives were women who helped women during labor, delivery, and recovery from birth. European, Indigenous, and African cultures all had midwives; in North America, most babies born before the 20th century were delivered by midwives. From the colonial period through the Constitutional era (1786–1791), abortion was of little interest to U.S. lawmakers, who considered it “women’s business.” Midwives, physicians, and the public alike did not believe a pregnancy could be confirmed during the first trimester, as people thought the absence of a menstrual cycle could result from a blockage as much as from pregnancy.

Using roots and plants such as ergot, indigo, and cotton root, or turpentine and quinine, was common to resume one’s period, or “suppress the courses,” as Document #7 below calls it. Women widely used such abortifacients as a natural part of reproduction and people openly described these herbs and medicines in midwifery handbooks, pharmacy guides, and home medical literature. Early American medical books gave value-neutral instructions for “suppressing the courses.”

19th and Early 20th Century

In the early 1800s through the early 20th century, a coalition of doctors backed by the American Medical Association, the Catholic Church, and tabloid newspapers began to campaign to make abortion care a crime. By the turn of the century, this coalition largely succeeded in limiting women’s reproductive choices in an attempt to assert the authority, legitimacy, and status of scientific medicine — which excluded women — over female midwives. White male physicians, lawmakers, and social scientists expressed public and repeated anxiety that the low birthrate of the white middle and upper class Protestants would lead to white Protestant people becoming a minority in the country.

In response, lawmakers removed the quickening distinction from the statutory laws of 10 of the 26 states between 1821 and 1880. In these states, abortion became criminalized from conception. For the first time, it was illegal for free women to bring on their menses in the first months of pregnancy. The first state to do this was Connecticut in 1821 (Document #8), where the General Assembly passed the nation’s first bill banning medicinal abortion after quickening. Those who provided the medicine — not the pregnant woman — faced prosecution. Within 20 years, 10 of 26 states followed suit with similar laws.

While people still used abortifacients, and abortifacients continued to be covertly advertised and sold as a cure for “feminine complaints,” lawmakers, physicians, and religious leaders now attached significant stigma to abortion care. Indeed, between 1821 and 1900, the United States moved from being a nation without abortion laws of any sort, to a nation where abortion was made illegal and often criminalized. These state laws supported by physicians, legislators and religious leaders turned abortion from “women’s business” to officially taboo.

Comstock Laws

In 1873, the federal government joined the argument. The federal Comstock laws ushered in a new era, authorizing Anthony Comstock of the post office to search anyone’s mail for any “obscene, lewd, lascivious, indecent, filthy, or vile article, matter, thing, device, or substance.” Since at this time, Comstock judged information about birth control and abortion care to be obscene, all women residing inside the United States struggled to access information about reproduction, contraception and abortion care. Comstock laws made it extremely difficult for women to know about — much less control — their own bodies legally, socially, or culturally.

Dozens of states soon passed bills mirroring the federal Comstock laws. In some cases, these bills signaled the first extreme legal restrictions on reproductive rights. Georgia, for example, had no such laws on the books until 1876, when a new statute declared abortion care “an assault with intent to murder.” In short order, state legislators made all abortion criminal except when necessary to “preserve the life” of the pregnant woman. This 1876 law, and many similar laws passed around the country, remained virtually unchanged until the 1960s. Despite Comstock being a “zombie law” unenforced for nearly a century, in March 2024, Supreme Court Justices Alito and Thomas appeared to invoke its legitimacy in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine. In their reading, the law continued to restrict the sending of medication abortion via the U.S. mail.

Sterilization

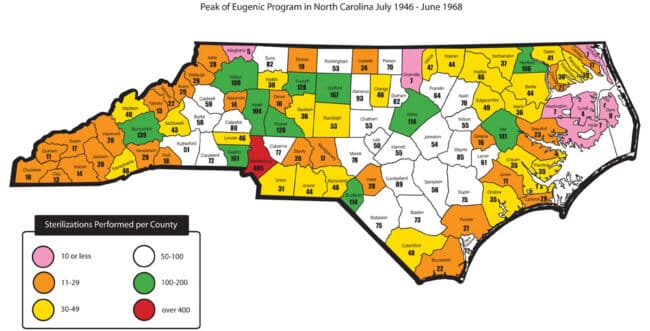

At the same time as abortion care was criminalized, legislators and physicians engaged in widespread sterilization of those who were Black, Indigenous, Puerto Rican, or immigrants, as well as people who had intellectual or developmental disabilities. In 32 states between 1929 and the mid-1970s, more than 60,000 women were forcibly sterilized in the United States. For example, in North Carolina, between 1929 and 1975, the state ordered the sterilization of more than 7,600 people. Eighty-four percent of these were women. More than 2,000 of those sterilized were minors at the time of their sterilization, most of them victims of sexual violence. Black North Carolinians represented 39 percent of those sterilized overall. As the Civil Rights Movement crested in the later 1960s, Black women made up 60 percent of those sterilized, even though they were only 25 percent of the population. After California and Virginia, North Carolina conducted the third highest number of sterilizations in the country. While we think this content is difficult for high schoolers, historians are aware that teenagers were often targeted, and keeping this information from them now is thus ethically problematic.

As can be seen in Document #13, children were also sterilized. North Carolinian Elaine Riddick, 13, became pregnant after being raped by a man in her neighborhood. In an office building in Raleigh, five men met to consider her fate — among them the state health director and a lawyer from the attorney general’s office. Board members concluded that Riddick was “feebleminded” and doomed to “promiscuity.” They recommended sterilization. After a social worker threatened her illiterate grandmother, Maggie Woodard, with losing her access to state food rations, Woodard marked an “X” on a sterilization consent form. Riddick gave birth to her son at 14 via c-section, after which the doctor sterilized her without her knowledge or consent. By 1970 between 25 and 45 percent of Native American women and 33 percent of women in Puerto Rico, a U.S. colony, had been sterilized.

Today, only Alaska and North Carolina have outlawed forced sterilization. Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia allow forced sterilization of people under specific circumstances. For more information, see this 2019 report from the National Women’s Law Center.

The Comstock laws meant that women had very little control over the knowledge produced about their bodies, as well as very little access to information about reproductive care, for 100 years, between the 1870s and the 1970s.

Civil Rights and Women’s Movements

A dramatic shift in knowledge-ownership and knowledge-creation occurred with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, and the 1970s feminist movement. Women in the Civil Rights Movement demanded medical care that included abortion care, and civil rights stalwarts like T. R. M. Howard responded. Civil rights activist Heather Booth activated her political network to form JANE, a safe underground abortion-care network in the 1960s. As scholar Ashley Farmer writes, “Before Roe v. Wade, lawyers, feminists, and Black Power activists like Florynce Kennedy worked to legalize abortion through Abramowicz v. Lefkowitz.” This was “a 1970 lawsuit that was the first constitutional challenge to abortion.” Flo Kennedy put women on the stand as expert witnesses, rather than medical professionals. Kennedy’s strategy of using women who had experienced illegal abortion eventually led to the Supreme Court deciding Roe v. Wade in 1973, that all of those who were pregnant had the Constitutional right to abortion care in the first six months of a nine-month pregnancy.

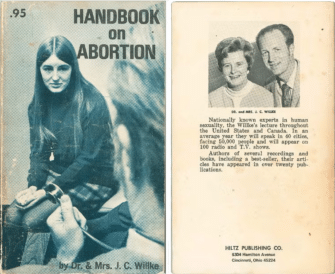

This was not a universally supported decision. In 1968, before Roe, Catholic bishops, doctors, nurses, lawyers, and housewives formed the National Right to Life Committee. They quickly expanded to include small numbers of non-Catholics, usually Protestants, Mormons, or Orthodox Christians. They stated their opposition to abortion care as a violation of the rights of the fetus. The graphic booklet, Handbook on Abortion, created by a Catholic doctor and nurse, John and Barbara Willke, quickly became “the bible of the pro-life movement.” New medical technologies such as the ultrasound allowed these activists to make a visual case that fetal bodies were equal to or had even more right to life than the pregnant mother.

Some groups who believed abortion morally wrong refused to participate in the political process and sought to end abortion care by “any means necessary.” In the 1980s and 1990s, Operation Rescue started the tactic of “rescue,” creating blockades in front of reproductive care clinics. Operation Rescue’s dramatic clinic blockades made it much more difficult to access abortion care. Extremists in this movement went further: Between 1977 and 2023, they carried out 531 assaults, made 383 death threats, three kidnappings, 42 bombings, 200 arsons, 492 clinic invasions, 18 attempted murders, and 11 murders of abortion care providers.

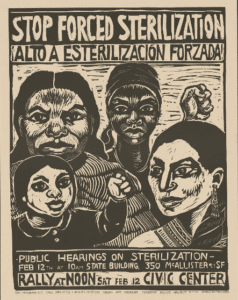

The women’s movement of the 1970s advocated for policy changes like equal pay for equal work, high quality child care, but too often centered white middle-class voices advocating legal abortion care. Black, Indigenous, Latinas, and women of color saw their struggle as wider than accessing abortion care: They demanded an end to programs sterilizing Black women, Indigenous women, Puerto Rican women, and immigrant women across the country. They led organizations advocating a “mother’s wage” to support low-income parents. They advocated for universal sex education as well as access to contraception, and high-quality, low-cost childcare.

Reproductive Justice

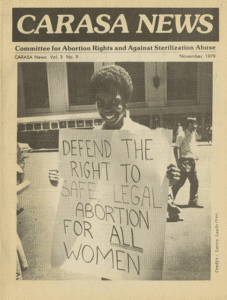

In the 1970s, and 1980s, these Black and brown women activists broadened the public’s understanding of abortion to insist on comprehensive access to healthy reproductive care — working at the same time to combat reproductive coercion and expand access to contraception and abortion. These issues, they insisted, could not be whittled down to a simple focus on abortion. CARASA, the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse, linked race, class and gender analysis, anticipating the intersectional and human rights approaches of the Reproductive Justice movement led by Black, Indigenous, and women of color in the 1990s.

The conceptual frame “Reproductive Justice” was a response to the whiteness of the early feminist health movement. Its Black, Indigenous, and women of color creators defined it as:

(1) the right to personal body autonomy (freedom to make choices about one’s body);

(2) the right to have children;

(3) the right to not have children;

(4) the right to parent the children people do have in safe and sustainable communities.

This framework had noteworthy similarities to the Haudenosaunee approach to abortion care before European contact.

When historians return to primary sources from the time, we see that in different eras, what people considered “acceptable” versus “unacceptable” for abortion care changed dramatically. We find ourselves debating what made it acceptable in certain eras, unacceptable in other eras. We also debate why at times people felt it had no moral weight, and at other times felt it represented the essence of freedom or family.

This collection of primary documents is offered as an invitation to students to return to these sources, think through these questions, and generate new questions to illuminate the field.

Wesley Hogan is a research professor at the Franklin Humanities Institute and History. She is the author of On the Freedom Side: How Five Decades of Youth Activists Have Remixed American History and Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC’s Dream for a New America, and co–facilitates a partnership between the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke, the SNCC Digital Gateway. Part of her current work is to facilitate a team of medical clinicians, researchers, and students doing oral histories of reproductive care providers in the post-Roe era.

Our Bodies Our Rights, by Meredith Stern, 2019. Source: Justseeds

Documents

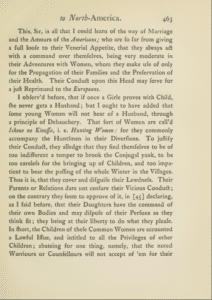

Document #1: Abortion Care on Turtle Island. Baron de Lahontan reports on his time among the Haudenosaunee, 1700

The focus of each generation of Haudenosaunee (also known by the French term, Iroquois) was to birth healthy children and eventually establish the next generation’s main family unit: the matrilineal longhouse. Neither sexual faithfulness nor monogamy was required to attain these ends. When European explorers, soldiers, and missionaries arrived, like French soldier Baron de Lahontan, they were surprised. Lahontan reported in 1700 that Iroquois “daughters have the command of their own bodies and may dispose of their Persons as they think fit.” What did Lahontan mean, “they have command of their own bodies?” Why do you think Lahontan was surprised by this?

|

|

| Source: New Voyages to North-America by Baron de Lahontan, Illinois University Library | |

Document #2: Cherokee Approach to Abortion Care, 1100 CE – 1800 CE

Cherokee society’s major goal was to secure the success of the next generation — distinct from the European colonists’ goal to pass property through the father’s line. Cherokee women shared their knowledge of contraception, menstruation, healthy pregnancy, and abortion only with other women. They knew that roots of Spotted Cowbane or Water Hemlock (cicuta maculate), prevented conception. They also used cotton root to induce abortion, and Black Haw to prevent miscarriage. Why do you think Cherokee women shared this herbal knowledge only with other women?

| Spotted Cowbane | Cotton Root | Black Haw |

Source: Water Hemlock or Spotted Cowbane, All-Creatures.org |

Source: Cotton Root, from the Sacred Journey School of Herbalism Facebook page |

Source: Black Haw, Master Gardeners of Northern Virginia, photo by Elaine Mills |

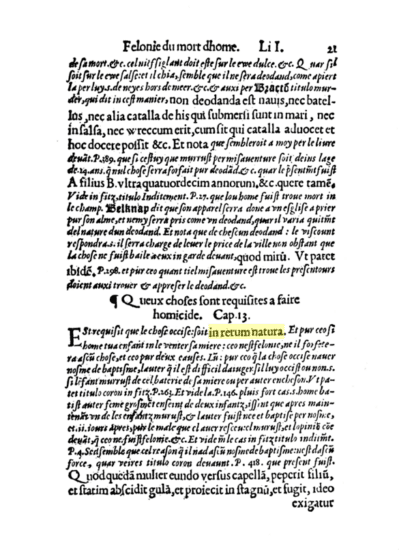

Document #3: Puritans’ Approach to Abortion Care, 1600s

In 1557, William Staunford summarized the English law requirements for homicide by stating that:

The thing killed must be in part of the world of physical beings (in rerum natura). So if one kills an infant in its mother’s womb, this is not a felony.

This law followed Christian Church teachings of the time that abortion was acceptable for married women until quickening, when Christians believed the soul entered the fetus. The legal status of abortion care remained like this — with women (rather than men, legislatures, or judges) deciding on abortion care — between 1200 and 1803 in England. The document makes a distinction between the “world of physical beings” and “the mother’s womb.” Why do you think the English made this distinction in the centuries before the invention of technologies like x-rays, ultrasounds, and CAT scans?

Documents #4 and 5: African Women’s Approaches to Abortion Care in Enslavement, 1600s–1865

In 1656, Elizabeth Keye successfully sued for her freedom (her mother was an enslaved Angolan owned by her father, a white, property-owning Englishman and member of the Virginia legislature). Keye won her suit based on centuries of Anglo-European legal custom of both patrilineal descent and the traditions of Christianity.However, in 1662, the Virginia Legislature reconsidered, overturning centuries of English Common Law: “All children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.” Why do you think the Virginia Legislature overturned English common law on this issue? Why do you think that 120 years later, when the “United States of America” was created under the U.S. Constitution, the entire nation adapted this law of children following the condition of the mother?

Elizabeth Keye, 1660s. Source: “1650s Virginia Court Records – Elizabeth Key – Slave or Free?,” Women in 17C Colonial America |

Virginia Changes Its Heredity Law, 1662 |

Document #6: Lu Lee, a midwife enslaved on a plantation straddling the Louisiana/Texas state line

Lee recalled how enslaved women shared knowledge of abortifacients in an interview with the Works Progress Administration, in the 1930s. Why do you think enslaved women and girls found it important to have access to abortion care (to “unfix” themselves), even when it was prohibited?

When women had babies they had old granny women on the place to look after them. They stayed in bed three days and got up on the fourth. But if they had a bad time they let them stay in bed four days. The women who had nursing babies did work around the house or in the spinning rooms so they be where they can suckle the babies. For the babies the granny women give them watermelon tea (pour hot water over watermelon seeds and let steep) to make they kidneys act. They give them catnip tea to break out the hives on them…

I have known too of women that got pregnant and didn’t want the baby and they unfixed themselves by taking calomel and turpentine. In them days the turpentine was strong and 10 or 12 drops would miscarry you. But the makers found what it was used for and they changed the way of making turpentine. It ain’t no good no more. They [women] used to take indigo to unfix themselves.

| Turpentine | Calomel Tablets |

Source: Amazon |

Source: Health Museum of South Australia, AR#5404, eHive |

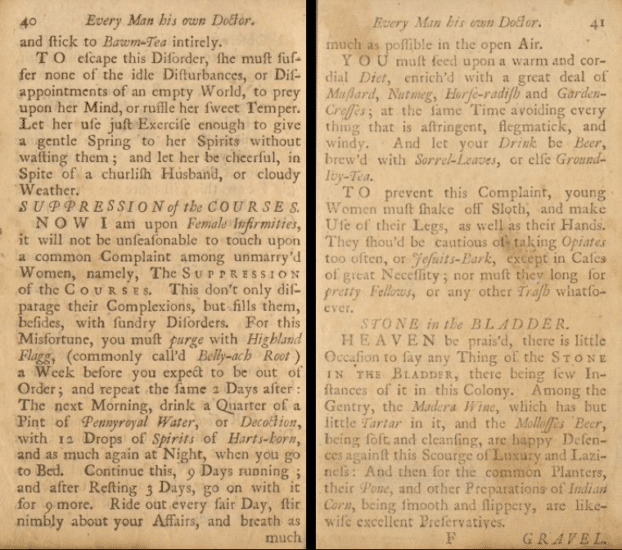

Document #7: Freed Women in the Colonies. Every Man his own Doctor: OR, The Poor Planter’s Physician (2nd edition, Annapolis + Williamsburg: William Parks, 1734. 1 shilling).

People living in Colonial America understood pregnancy differently than today. From the colonial period through the Constitutional era (1786–1791), abortion was of little interest to U.S. law makers, who considered it “women’s business.” At this time, abortion before quickening was not just legal, it was morally neutral. Benjamin Franklin tacked this pamphlet onto his popular book on basic math, Fisher’s Arithmatik. The anonymous (male) physician writes of abortion (here referred to as “suppression of the courses”). The document is printed in the original, but also typed because it is hard to read. Besides the medicine prescribed, what behavior change does the physician recommend?

NOW I am upon Female Infirmities, it will not be unseasonable to touch upon a common Complaint among unmarry’d Women, namely, THE SUPPRESSION OF THE COURSES. This don’t only disparage their Complexions, but fills them, besides, with sundry Disorders. For this Misfortune, you must purge with Highland Fagg, (commonly call’d Belly-ach Root) a Week before you expect to be out of Order; and repeat the same 2 Days after: The next Morning, drink a Quarter of a Pint of Pennyroyal Water, or Decoction, with 12 Drops of Spirits of Harts-horn, and as much again at Night, when you go to Bed. Continue this, 9 Days running; and after Resting 3 Days, go on with it for 9 more. Ride out every fair Day, stir nimbly about your Affairs, and breath as much as possible in the open Air. YOU must feed upon a warm and cordial Diet, enrich’d with a great deal of Mustard, Nutmeg, Horseraddish, and Garden-Cresses; at the same time avoiding every thing that is astringent, flegmatick, and windy. And let your Drink be Beer, brew’d with Sorrel-Leaves, or else Ground-Ivy-Tea. TO prevent this Complaint, young Women must shake off Sloath, and make Use of their Legs, as well as their Hands They should be cautious of taking Opiats too often, or Jesuits-Bark, except in Cases of great Necessity; nor must they long for pretty Fellows, or any other Trash, whatsoever.

Source: Every man his own doctor by John Tennent, National Library of Medicine Digital Collections

Document #8: Connecticut becomes the first state to pass a law banning abortion in 1821.

Who does the law say should be punished? What do you think might make this law difficult to enforce? “Every person who shall, wilfully and maliciously, administer to, or cause to be administered to, or taken by, any person or persons, any deadly poison, or other noxious and destructive substance, with an intention him, her or them, thereby to murder, or thereby to cause or procure the miscarriage of any woman, then being quick with child, and shall be thereof duly convicted, shall suffer imprisonment, in new-gate prison, during his natural life, or for such other term as the court having cognizance of the offence shall determine.”

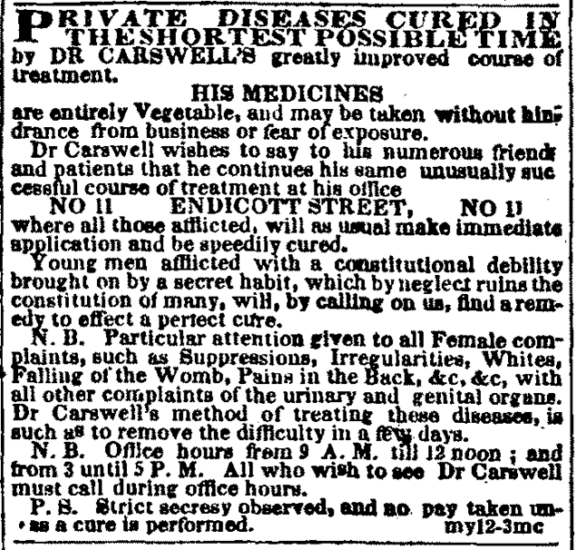

Document #9: Abortion practitioner ad, 1845

Even as some states made abortion care illegal, local newspapers of record featured advertisements for abortion care services. As one example, the Boston Daily Times regularly printed this ad for a Dr. Carswell in 1845 — the same year Massachusetts outlawed abortion care. Without using direct terms like “pregnancy” or “abortion,” the ad’s “particular attention given to all female complaints. . . such as to remove the difficulty in a few days” with “strict secrecy observed” makes clear that Dr. Carswell is an abortion care practitioner.

Boston Daily Times, June 19, 1845.

Documents #10 and #11. Anthony Comstock forms the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.

In 1873, the federal government’s Comstock laws ushered in a new era, authorizing Anthony Comstock of the post office to search anyone’s mail for any “obscene, lewd, lascivious, indecent, filthy, or vile article, matter, thing, device, or substance.” Since at this time, Comstock judged information about birth control and abortion care to be obscene, all women residing inside the United States struggled to access information about reproduction, contraception, and abortion care. Comstock laws made it extremely difficult for women to know about — much less control — their own bodies legally, socially, or culturally. Why do you think Comstock judged information about reproduction to be “obscene”? How might women get this information, if they couldn’t get it in the mail?

| New York Society for the Suppression of Vice | Anthony Comstock |

New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, 1873. Source: Public access |

Portrait of Anthony Comstock. Source: Public access |

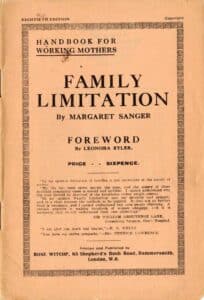

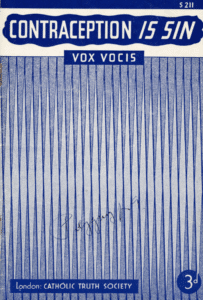

Documents #12 and #13: Comstock Law Enforcement, 1870s-1960s

Look closely at the text on each pamphlet cover. Why do you think the first pamphlet was banned? Why do you think the second pamphlet was allowed?

| Under Comstock, this pamphlet was banned: | Under Comstock, this pamphlet was not banned: |

Family Limitation pamphlet by Margaret Sanger (1924). Source: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan |

Contraception Is Sin pamphlet, Catholic Truth Society. Source: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan |

Documents #14 and 15: Sterilization Campaigns 1929–1970s

At the same time as abortion care was criminalized, legislators and physicians engaged in widespread sterilization of those who were Black, Indigenous, Puerto Rican, or immigrants, as well as people who had intellectual or developmental disabilities. In 32 states and colonies including Puerto Rico and Guam, between 1929 and the mid-1970s, more than 60,000 women were forcibly sterilized in the United States.

One of these people, North Carolinian Elaine Riddick, 13, became pregnant after being raped by a man in her neighborhood. In an office building in the state capitol, five men met to consider her fate — among them the state health director and a lawyer from the attorney general’s office. Board members concluded that Riddick was “feebleminded” and doomed to “promiscuity.” They recommended sterilization. After a social worker threatened her illiterate grandmother, Maggie Woodard, with losing her access to state food rations, Woodard marked an “X” on a sterilization consent form. Riddick gave birth to her son at 14 via c-section, after which the doctor sterilized her without her knowledge or consent. At 19, Riddick discovered what had happened. What does Riddick mean, “they took something from me both times?” Who do you think should be held responsible?

Document (Interview) #14: “I was raped by a perpetrator,” Riddick testified in 2010, noting that the rapist was never charged. “And then I was raped by the state of North Carolina. They took something from me both times,” she said. “The state of North Carolina, they took something that was God given.” See a four-minute interview with Riddick here.

Document (Map) #15: Peak of Sterilization Program in North Carolina, by county, July 1946–June 1968. Which counties have the highest rates of sterilization? Why do you think these counties had such high rates? Which counties had the lowest rates, and why?

Peak of the Eugenic Program in North Carolina, July 1946 – June 1968. Source: North Carolina Department of Administration

Documents #16 and #17: Feminism and Womanism, 1970s–1990s

What changed in the 1970s that led lawyers like Florynce Kennedy and justices on the Supreme Court to reconsider abortion, and decide to make it legal?

Florynce Kennedy, the lawyer who put women on the stand as experts on abortion care in 1970 for the case Ambramowicz v. Lefkowitz, and brought the first constitutional challenge to support legal abortion. Source: L’Officiel |

The Supreme Court justices who decided Roe v. Wade on Jan. 22, 1973. Members of the Supreme Court on April 20, 1972. Front row, from left: Justices Potter Stewart and William O. Douglas; Chief Justice Warren E. Burger; Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and Byron R. White. Back row, from left: Justices Lewis F. Powell Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Harry A. Blackmun and William H. Rehnquist. Source: Photographer John Rous/AP |

Documents #18 and #19: The Pro-Life Movement, 1960s–2000s

In 1968, Catholic bishops, doctors, nurses, lawyers, and housewives formed the National Right to Life Committee. They quickly expanded to include small numbers of non-Catholics, usually Protestants, Mormons, or Orthodox Christians. They stated their opposition to abortion care as a violation of the rights of the fetus. The booklet, Handbook on Abortion, with photographs of fetuses, created by a Catholic doctor and nurse, John and Barbara Willke, quickly became “the bible of the pro-life movement.” Why do you think these groups began to organize before Roe v. Wade for the rights of the fetus? What role do you think photographs of fetuses played in the movement?

Congressman Henry Hyde. Source: Public access |

Handbook on Abortion by John and Barbara Willke, featuring a photo of Marie Willke, and the back cover, featuring Jack and Barbara Willke. Images from the Handbook on Abortion, 1971 edition. Source: Slate |

Documents #20 and #21: Operation Rescue 1980s–1990s

In the 1980s and 1990s, Operation Rescue started the tactic of “rescue,” creating blockades in front of reproductive care clinics. Operation Rescue’s dramatic clinic blockades made it much more difficult to access abortion care. Extremists in this movement went further: Between 1977 and 2023, they carried out 531 assaults, made 383 death threats, three kidnappings, 42 bombings, 200 arsons, 492 clinic invasions, 18 attempted murders, and 11 murders of abortion-care providers. Why do you think these individuals and groups felt the need to move outside the political process?

Operation Rescue protesters in Wichita, 1991. Source: KCUR 89.3 |

Scott Roeder, convicted of murdering prominent Kansas abortion provider Dr. George Tiller, at his trial on Jan. 28, 2010, in Wichita, Kan. Source: Photographer Jeff Tuttle, NBC News |

Documents #22 and #23: Reproductive Justice 1970s–2000s

Black, Indigenous, Latina, and women of color saw their struggle as wider than simply accessing abortion care: They demanded an end to programs sterilizing Black, Indigenous, Puerto Rican, and immigrant women across the country. They worked at the same time to combat reproductive coercion and expand access to birth control and abortion. One of the organizations they formed was CARASA, the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse. Why do you think they insisted on linking getting rid of forced sterilization and making abortion care more accessible?

Stop Forced Sterilization, by Rachael Romerao, San Francisco Poster Brigade. Source: Library of Congress |

Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse (CARASA) News, v. 3, no. 9 (1979). Source: Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan |

Document #24: The Women’s Community Health Center in 1979

In an early call for body autonomy, the Boston Women’s Community Health Center said that a focus on abortion alone was not enough. Why do you think they called for both the right to have children and the right not to have children? Why did they include the right to parent in safe and sustainable communities?

Being able to choose whether and when to have children is an integral part of that control [over our bodies and reproductive lives]. These decisions, however, are difficult to make if the means to carry them through are not readily available. We must have safe and effective birth control, access to abortion regardless of economic status, and freedom from forced sterilization and medical experimentation. Every woman must have a decent income, high quality health care, childcare as needed, and the freedom to define her own sexuality.

Questions for Further Study and Enrichment

To learn more, students can explore contemporary debates within the historical community about abortion care. Students can research the scholarship on any of the topics below and join in the conversations historians are having today.

-

- Why did abortion care become controversial in the 1800s, after being seen as a private “women’s issue” in both Europe and North America for many centuries?

- Did fears of falling white birth rates drive campaigns to restrict access to abortion care in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries?

- Why did some women join the movement to restrict access to abortion care?

- Was restricting access to abortion care popular among citizens in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries? Some scholars see it as a popular, if religious-minority-led, movement. Others see it as an anti-democratic takeover by a small elite at moments of great change in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

- Echoing the veterans of the U.S. Revolution, many have argued that the right to control one’s own medical decisions and decisions to parent is a basic human freedom. Was it realistic to think about control over one’s reproduction as an essential component of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” promised in the Declaration of Independence?

- How much of the current political fight over abortion care is driven by the violent attacks on women’s health care clinics and reproductive care providers in the 1980s and 1990s?

- In what ways does the call for Reproductive Justice of the 1990s echo the attitudes of the Haudenosaunee prior to European contact?

Bibliography

Baker, Cathleen et.al., curators. “Birthing Reproductive Justice” online exhibit at the University of Michigan, accessed online 2 Feb. 2024.

Bridges, Khiara, Reproducing Race: An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of Racialization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Coke, Edwardo. The Third Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England: Concerning High Treason, and Other Please of the Crown and Criminal Causes 50. Getzville, NY: William S. Hein Co. 1986. Original publication 1797.

DeLisle, Christine Taitano. Placental Politics: CHamoru Women, White Womanhood, and Indigeneity under U.S. Colonialism in Guam. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2022.

Farmer, Ashley. “Black Women’s Expansive Vision For Reproductive Freedom.” Black Perspectives. 4 Aug. 2022. Accessed online 2 Feb. 2024.

Greenlee, Cynthia. “T. R. M. Howard, Civil Rights Rabble-Rouser, Abortion Provider.” Dissent. 16 May 2013. Accessed online 2 Feb. 2024.

Haugeberg, Karissa. Women Against Abortion: Inside the Largest Moral Reform Movement of the Twentieth Century. Champagne-Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Hening, William Waller, ed. The Statutes at Large; Being a Collecion [sic] of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619. NY: R & W & G Bartow, 1823. 2:170.

Holland, Jennifer L. “Abolishing Abortion: The History of the Pro-Life Movement in America.” Organization of American Historians, 2016. Accessed online 2 Feb. 2024.

Latimer, Heather. “Abortion Regulation as the Afterlife of Reproductive Slavery: Or, a Call to Make Abortion Natural Again.” Feminist Studies 48:2 (2022) 342-366.

Lu Lee quoted in George P. Rawick, ed. The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, Supplement Series 2, Vol. 5, Texas Narratives, Part 6 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979,) 2299.

Mohr, James C. Abortion in America: the Origins and Evolution of National Policy. NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 1979.

Morgan, Jennifer. Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic. Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 2021.

Randolph, Sherie M. Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Spivack, Carla. “’To “Bring Down the Flowers’: The Cultural Context of Abortion Law in Early Modern England Law in Early Modern England,” William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law 14: 1 (2007) 107-151.

Staunford, William. Les Plees Del Coron 21. P.R. Glazenbrook ed. London: Profl Books Ltd., 1971. Originally published in 1557.

“Study Confirms Age of Oldest Fossil Human Footprints in North America,” 5 Oct. 2023, US Geological Survey. Accessed online, 11 Nov. 2023.

Theobald, Brianna. Reproduction on the Reservation: Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Colonialism in the Long Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Wilkie, Laurie, “Expelling Frogs and Binding Babies: Conception, Gestation and Birth in 19th-Century African-American Midwifery,” World Archaeology 45: 2 (June 2013) 272-284.

Women’s Community Health Center collective, quoted in Holmes, Helen, et. al. Birth Control and Controlling Birth: Women-Centered Perspectives. Clifton, NJ: Humana Press, 1980.

Additional Resources

These are selected resources, not a comprehensive list. More will be added.

Organizations

Advocates for Youth works in the Unted States and in the global south to advocate for youth sexual health and rights.

We Testify supports people who’ve had abortions to share their stories, particularly those of color, those from rural and conservative communities, those who are queer-identified, those with varying abilities and citizenship statuses, and those who needed support when navigating barriers while accessing abortion care.

Abortion Diary is a podcast that allows people to share and listen to stories about abortions.

Books

The Women Who Caught the Babies: A Story of African American Midwives by Eloise Greenfield, illustrated by Daniel Minter

Let’s Talk About Abortion by Carly Kol, illustrated Emulsify

Witches, Midwives, & Nurses: A History of Women Healers, 2nd edition, by Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English

Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood by Michele Goodwin

Films

Belly of the Beast, 2020, by Erika Cohn, et al. 81 minutes. Women Make Movies. Filmed over seven years with extraordinary access and intimate accounts from currently and formerly incarcerated people, this Emmy-winning documentary exposes a pattern of illegal sterilizations, modern-day eugenics and reproductive injustice in California prisons. (Description from film distributor.)

Birthing A Nation: The Resistance of Mary Gaffney, 2023, by Nazenet Habtezghi, 19 minutes. MTV and Firelight Media. The story of forced reproduction in the antebellum South and the agency of Mary Gaffney, an enslaved woman who takes control of her body and fertility. Includes commentary by historians Tera Hunter, Jennifer Morgan, and Daina Ramey Berry. (Description from film distributor.)

Imelda Is Not Alone, 2023, by Paula Heredia, 31 minutes. Imelda Cortez, aged 19, arrives at the hospital bleeding after giving birth in a latrine. She is handcuffed to the hospital bed, arrested on suspicion of abortion, and later charged with attempted and aggravated murder. Imelda’s only hope at freedom is a local citizen’s movement that dares to defend women who are persecuted under El Salvador’s total ban on abortion. The result is a shocking account of an ongoing human rights crisis and a moving portrait of those who fight for a better society. (Description from film distributor.)

The Janes, 2022, by Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes, 102 minutes. The story of a group of unlikely outlaws. Defying the state legislature that outlawed abortion, the Catholic Church that condemned it, and the Chicago Mob that was profiting from it, the members of Jane risked their personal and professional lives to help women in need. In the pre-Roe v. Wade era — a time when abortion was a crime in most states and even circulating information about abortion was a felony in Illinois — the Janes provided low-cost and free abortions to an estimated 11,000 women. (Description from film distributor.)

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn