As we celebrate Howard Zinn’s centennial, we highlight people’s historians from long before and after the publication of A People’s History of the United States to help place Zinn’s work on a long and ongoing continuum. Incorrectly, some people refer to Zinn as the first or only people’s historian. While we have great respect and appreciation for Zinn’s work, it is important to recognize those who proceeded him and those who continue to expand the field today.

As we celebrate Howard Zinn’s centennial, we highlight people’s historians from long before and after the publication of A People’s History of the United States to help place Zinn’s work on a long and ongoing continuum. Incorrectly, some people refer to Zinn as the first or only people’s historian. While we have great respect and appreciation for Zinn’s work, it is important to recognize those who proceeded him and those who continue to expand the field today.

A number of the people we feature were not official historians. Instead, as Pero Gaglo Dagbovie says in African American History Reconsidered, they were “historians without portfolio.” For example, Black women were long excluded from formal history education in the United States (Marion Thompson Wright became the first Black woman to earn a PhD in history in the United States in 1940.) Therefore, many Black women recorded and told the radical history of their people as novelists, librarians, journalists, and self-taught historians.

This is just a small collection of thousands of people’s historians. We hope their stories lead you to explore more.

|

James PenningtonAfter escaping the brutality of slavery in Maryland in 1827, James Pennington (1807–1870) took the Underground Railroad north and eventually became an orator, writer, minister, and abolitionist. After becoming ordained at Yale University, Pennington performed the wedding of Frederick Douglass and Anna Murray. He later became pastor at Faith Congregational Church in Hartford, Connecticut. In 1841, Pennington published the book A Textbook of the Origin and History of the Colored People, which challenged prevailing assumptions about African American inferiority. Pennington later supported the Amistad captives, helping to create the Union Missionary Society (later the American Missionary Society). Learn more about Pennington and his lifelong commitment to abolition in the article “Reverend James Pennington: A Voice for Freedom.” |

|

Francis Ellen Watkins HarperFrances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911) was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1825. After teaching in Pennsylvania and Ohio for two years, she traveled the U.S. speaking on the abolitionist circuit and assisting in the Underground Railroad. In addition, Harper was a prolific and celebrated writer. Throughout her life, she published numerous collections of poetry, including Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects and Sketches of Southern Life. In short time, Harper became the most celebrated female African American writer in the United States. Here is an excerpt from a poem she wrote about slavery: And mothers stood with streaming eyes After the end of the Civil War, Watkins supported the advancement of civil rights for African Americans, women’s rights, and equality in education for all. Read more at the Archives of Maryland and ExplorePAHistory.com, and also more at the Zinn Education Project here and here. |

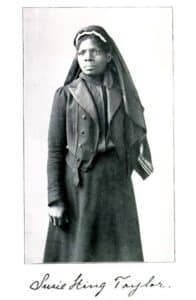

Susie Baker King TaylorSusie Baker King Taylor (1848–1912) was the first Black educator to openly teach Black students in Georgia and the only Black woman to publish an account of the Civil War. Susie Baker King Taylor was born enslaved on the Grest Farm in Liberty County, Georgia, where her mother was enslaved by the Grest family. When she was 7, Baker and her brother were sent to live with their grandmother in Savannah. Despite being illegal, both children attended two secret schools taught by Black women. Baker would use the reading and writing skills she learned in secret to continue to educate Black people for decades to come. After the war, Baker King returned to Savannah where she established a school for freed Black children. Later, she moved to Boston, where she would ultimately self publish her memoir, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd US Colored Troops, in 1902. Her reminiscences included a celebration of Black women’s role in seizing freedom during the war. Read more at Black Past. |

|

George Washington WilliamsGeorge Washington Williams (1849–1891) was a 19th century American historian most famous for his History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880; as Negroes, as Slaves, as Soldiers, and as Citizens (1882), and A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865 (1887). In 1890, Williams studied conditions in the Belgian Congo at the commission of President Benjamin Harrison and wrote to the Belgian Crown about the atrocities committed against Africans. Although he hoped to spark a movement in protest of the Belgian government’s role in its African colony, little came of his effort in the United States. He moved to England to work on a book on Africa. Williams fell ill shortly after arriving in England and died at the age of 41. [Excerpted from Black Past.] Williams is included in the lesson, Congo, Coltan, and Cell Phones: A People’s History. |

|

Pauline Elizabeth HopkinsNovelist, journalist, playwright, historian, and editor Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins (1859–1930). Hopkins was a pioneering writer who used traditional literary forms to explore race and racism and specifically the experiences of Black women through her plays, novels, and short stories. In addition to her fiction, Hopkins also worked as columnist and editor of the Colored American Magazine where she wrote biographies of Black historical figures, in part to serve as inspiration to take action in the continued Black freedom struggle. In chapter four of African American History Reconsidered, historian Pero Gaglo Dagbovie describes Hopkins’ approach to history: “A self-proclaimed historian, Hopkins introduced her best-known novel as being a historical study grounded in rigorous research. Philosophically, Hopkins argued that history was instructive because of its direct connection with the present and future. She viewed the past as being part of a larger historical continuum, part of a vast body of interconnected ideologies and events. Though she ‘tried to tell an impartial story,’ Hopkins was forthright in the need for Black-authored revisionist historical accounts. ‘No one will do this for us; we must ourselves develop the men and women who will faithfully portray the inmost thoughts and feelings of the Negro with all the fire and romance which lie dormant in our history, and, as yet, unrecognized by writers of the Anglo-Saxon race.” Read more at the Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins Society website. |

|

Delilah Leonium BeasleyDelilah Leonium Beasley (1867–1934) was a pioneering Black journalist and self-trained historian who spent years documenting Black life — particularly the lives of every day Black women — throughout California. Beasley was born in Cincinnati, Ohio around 1867, shortly after the end of the Civil War. While attending the city’s segregated public schools as a teenager, she started publishing short social reports on the Black community for both the local Black and white newspapers. By the early 1900s, Beasley had moved to Oakland, California where she immersed herself in local Black history and Black women’s club network. Beasley is perhaps best known as a pioneering journalist — she was the first Black woman to be regularly published in a major metropolitan newspaper with her column in the Oakland Tribune — but her work as a researcher and historian are no less important. In 1919, Beasley self-published Negro Trail Blazers of California, which she meticulously researched by poring through university archives, collecting and reading through family letters, and interviewing every day Black people throughout the entire state. Beasley put herself into debt in order to publish her book, and over time the cumulative effects of overwork and financial instability damaged her health. Beasley died in 1934 after decades of writing about, learning from, and fighting to protect Black people in California. Learn more about Beasley at Black Past. |

|

|

|

Leila Amos PendletonLeila Amos Pendleton (1868–1938) was a Black community activist, writer, and teacher in Washington’s public schools. Pendleton used her position as a teacher and a writer in the segregated Washington, D.C., schools to promote the study of Black history. In 1915, Pendleton published her seminal work, A Narrative of the Negro. Three years later, W. E. B. Du Bois “hailed her book The Negro as the first major study of African descendants throughout the diaspora.” While not as scientific as Du Bois’s later work, Pendleton’s biographical sketches were wide reaching and ambitious for her young audience. In chapter four of African American History Reconsidered, historian Pero Gaglo Dagbovie continues to describe Pendleton’s work: [A Narrative of the Negro] addressed Africans’ lives from ancient times through the era of colonialism – blacks in Haiti, Brazil, Jamaica, and Bermuda, and black American life from the colonial era though ‘the nadir.’ Her young audience did not prevent Pendleton from embracing a militant tone. She chastised King Leopold of the Belgian Congo and the violent nature of the colonial conquest, called slavery ‘evil,’ and condemned the ‘long series of brutal outrages, murders, mailings, beatings, burnings’ and ‘barbarous lynchings’ of African Americans. The bulk of Pendleton’s study addressed African American history from the American Revolution through ‘the nadir,’ and in the tradition of African American juvenile literature it relied heavily on many brief biographical sketches of a range of black leaders. Renowned Harlem renaissance novelist and Crisis literary editor (1919-1926) Jessie Fauset heralded Pendleton’s book: ‘Now, at last, it would seem, we have an historian who has arisen in answer to our need.’ Learn more about Pendleton and A Narrative of the Negro at Documenting the American South. |

W. E. B. Du BoisW. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) was one of the most important activist scholars of the 20th century. Du Bois, a sociologist, historian, Pan-Africanist, author, and editor, was one of the co-founders of the NAACP in 1909, leader of the Niagara Movement, and editor of the NAACP’s journal The Crisis. His collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, was a seminal work in African-American literature; and his 1935 Black Reconstruction in America challenged the prevailing ideas about the Reconstruction era of the United States. Continue reading at the Zinn Education Project’s W. E. B. Du Bois This Day in History post. |

|

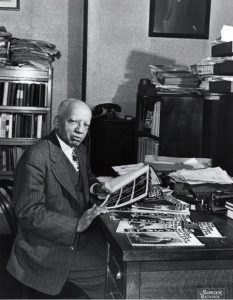

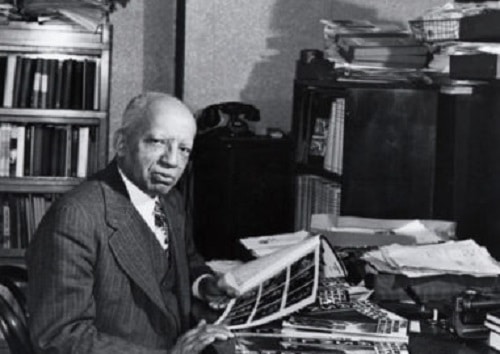

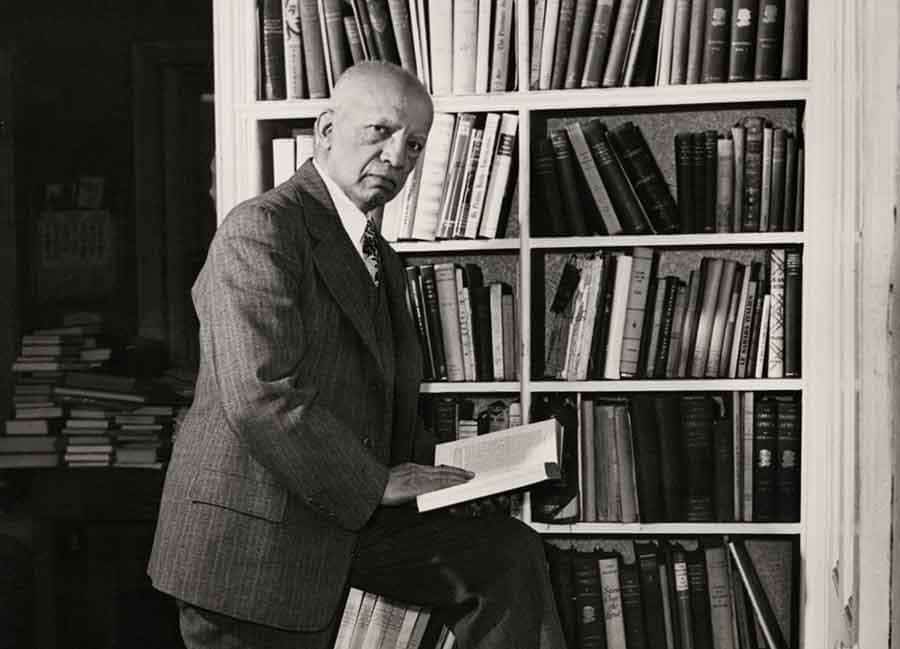

Carter G. WoodsonCarter G. Woodson (1875–1950) was an author, educator, and publisher. According to Black Past, Woodson was “Deservingly dubbed “The Father of Black History.” He was, simply put, a Black history institution builder.” On Feb. 7, 1926, Woodson initiated the first celebration of Negro History Week which led to Black History Month, to extend and deepen the study and scholarship on African American history, all year long. In 1915, Woodson published his first book, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, and co-founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH). In 1916, he singlehandedly launched The Journal of Negro History, now The Journal of African American History. In 1918, Woodson published A Century of Negro Migration and became the principal of Armstrong Manual Training School, Washington, D.C. From 1919 until 1920, he was the Dean of Howard University’s School of Liberal Arts and from 1920 until 1922, he served as a dean at West Virginia Collegiate Institute. In 1921, he published The History of the Negro Church and founded the Associated Publishers, Inc. After founding the , he also became active in black organizations like the NAACP, the National Urban League, the Friends of Negro Freedom, and the Committee of 200. [Excerpted from profile of Carter G. Woodson at Black Past.] In 1922, he published the first edition of his popular The Negro in Our History and decided to commit his life’s work, routinely laboring 18 hours per day, to the ASNLH and the early black history movement. For more on Woodson, read Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching and visit the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site (National Park Service) and statue in Washington, D.C. |

|

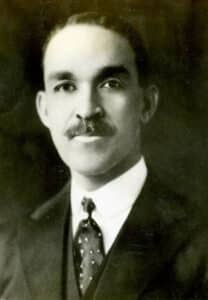

Benjamin Griffith BrawleyBorn in Columbia, South Carolina, Benjamin Griffith Brawley (1882–1939) authored numerous books, was a college professor, and also served as the first dean of Morehouse College from 1912 to 1920. In 1937, Brawley became chair of the English department at Howard University in Washington, D.C. According to Black Past, Throughout his scholarly career, Brawley had published several books, including A Short History of the American Negro (1921) and several essays, book reviews and articles of social commentary. Some of his books were used in colleges and universities around the country and were suggested reading in schools. Read more at Black Past. |

|

Zora Neale HurstonBorn in Harlem, Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) was a prolific writer and a skilled anthropologist from the Renaissance to the Civil Rights era. Born in 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama, she grew up in Eatonville, Florida, and eventually settled in Baltimore, where she completed her education at Morgan Academy and Howard University. With Langston Hughes and Wallace Thurman, Hurston in the late 1920s edited the short-lived magazine Fire! Again with Langston Hughes, in 1930 she wrote her first play titled Mule Bone, a comedy about African American rural folk life. Four years later, Hurston published her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, loosely based on the life of her father, a rural minister. Hurston’s most famous work, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was published in 1937. Read more at Black Past. |

|

Luther Porter JacksonAfrican American civil rights activist, historian, journalist, and much more, Luther Porter Jackson (1892–1950) was a professor of history at Virginia State College in Petersburg for nearly thirty years and authored Free Negro Labor and Property Holding in Virginia, 1830–1860 in 1942. Jackson actively challenged segregation in Richmond’s public transit system, authored a weekly newspaper column titled “Rights and Duties in a Democracy,” and helped found the Petersburg League of Negro Voters in 1935. Read more about Jackson and his contributions to history and struggle at Encyclopedia Virginia. |

|

|

Merl Raymond EppseAfter graduating from Drake University and Columbia University’s Teachers College, Merl Raymond Eppse (1893–1967) authored many books and was a history professor at Tennessee State University for over three decades. From 1948 to 1949, Eppse served as president of the Tennessee Negro Education Association, and Wilberforce University awarded him an honorary doctorate of laws in 1953. In order to publish his numerous books, Eppse founded the National Publication Company in Nashville, Tennessee. According to Murry R. Nelson, “Merl Eppse was one of the first educators to write a U.S. history textbook that presented the history of U.S. Blacks in an integrated manner.” Read the archived papers of Merl Raymond Eppse at the Tennessee State Library and Archives. |

Melville J. HerskovitsAfter serving in France in the U.S. Army Medical Corps during World War I, Melville J. Herskovits (1895–1963) turned to the study of history and anthropology. In 1925, Herskovits became assistant professor of Anthropology at Howard University, and in 1927 he moved to Northwestern University, where he became a full professor and helped to create the Department of Anthropology, serving as its first chairman in 1938. According to Northwestern University, “In 1948, he established the Program of African Studies and became its first director. In 1961, Northwestern appointed Herskovits to the Chair of African Studies, the first such position in the United States.” Among his many books, Herkovits published The Myth of the Negro Past (1941), Man and His Works (1948), and The Human Factor in Changing Africa (1962). Learn more about Melville J. Herskovits at Northwestern’s Herskovits Library of African Studies website. |

|

Shirley Graham Du BoisShirley Graham Du Bois (1896–1977) was the first Black woman to write and produce an all Black opera. She earned a master’s degree in music history, and, according to Pero Gaglo Dagbovie’s African American History Reconsidered, was a “woman of many dimensions and talents [who] lived many lives.” At times, Graham Du Bois was a composer, a playwright, an actress, a novelist, an activist, and a biographer, among other things. She published 13 biographies of famous figures in Black history. She was also married to historian W. E. B. Du Bois. Read more about Shirley Graham Du Bois at Black Past, and in this 2019 essay by Bettina Aptheker Shirley Graham Du Bois’s Biographical Writings. |

|

Rayford W. LoganTwentieth Century Black historian Rayford Whittingham Logan (1897–1982) was born on January 7, 1897, in Washington, D.C., to working class parents. Logan spent his formative years in Washington, D.C. While in high school, he was taught by Carter G. Woodson. A bright student, Logan was honored with a scholarship to Williams College where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1917. Immediately, he joined the U.S. Army in World War I and like many black veterans of that era, was disillusioned as he witnessed the racism perpetrated against black troops by white officers. After the war, Logan worked in France with W. E. B. Du Bois on the second Pan African Congress in 1921, where he also became friends with Dantès Bellegarde, the Haitian minister to the League of Nations, who was an outspoken opponent of colonialism. Logan returned to the United States in the early 1920s and began his teaching career at Virginia Union University in Richmond. During the next decade, Logan spoke out against Jim Crow and assisted local blacks with voter registration. In 1930 Logan began his Ph.D. studies at Harvard University. His Harvard dissertation became his first book, The Diplomatic Relations of the United States with Haiti-1776-1891 (1941). However, he still produced articles in scholarly and popular journals, as well as newspapers critiquing American racism. [Excerpted from profile of Rayford W. Logan at Black Past.] |

|

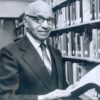

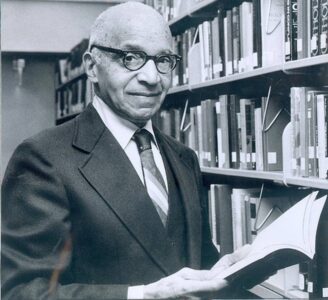

Benjamin Arthur QuarlesBenjamin Arthur Quarles (1904–1996) was born in Boston and was known as a prolific writer, a renowned historian, and a revered educator. After attending Shaw University, the oldest HBCU in the South, Quarles earned a M.A. and Ph.D. before returning to teach at Shaw. In 1953, Quarles moved to Baltimore where he led the History department at Morgan State College (now University). At Morgan, Quarles reached near-legendary status as the long-time head of the History Department (1953-1974), a revered teacher and counselor, an intellectual and professional mentor for two generations of African American scholars, and an internationally-acclaimed historian of the Black experience in the United States. Quarles published ten books and hundreds of articles during his life. Four of his books — Frederick Douglass, The Negro in the American Revolution, The Negro in the Making of America, and Black Abolitionists — garnered national attention and deepened the historical understanding of African Americans. Learn more about Quarles at Black Past. |

|

|

John Hope FranklinJohn Hope Franklin (1915–2009), one of the most important historians of the 20th century, was born Jan. 2, 1915, in Rentiesville, Oklahoma. He was raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His father, Buck Colbert Franklin, was a lawyer and is best known for defending African American survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre. Here is a quote from Franklin on reparations in Indyweek, People are running around apologizing for slavery. What about that awful period since slavery — Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and all the rest? And what about the enormous wealth that was built up by Black labor? If I was sitting on a billion dollars that someone had made when I sat on them, I probably would not be slow to apologize, if that’s all it takes. I think that’s little to pay for the gazillions that Black people built up — the wealth of this country — with their labor, and now you’re going to say I’m sorry I beat the hell out of you for all these years? That’s not enough. |

|

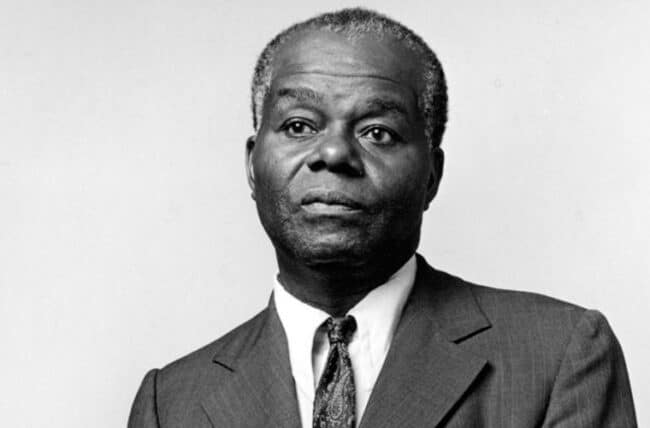

John Henrik ClarkeOn Jan 1, 1915, Dr. John Henrik Clarke (1915–1998) — a Pan-Africanist American writer, historian, professor, and a pioneer in the creation of Africana studies and professional institutions in academia — was born in Union Springs, Alabama. His father was a sharecropper and his mother laundered clothing. They named him John Henry Clark, and he later altered the spelling of his middle and last names to reflect his chosen identities and values. My daddy wanted me to be a farmer; feel the smoothness of Alabama clay and become one of the first Blacks in my town to own land. But, I was worried about my history being caked with that southern clay and I subscribed to a different kind of teaching and learning in my bones and in my spirit. Clarke was a prominent figure during the Black Power Movement, a professor of Africana studies at Hunter College and Cornell University, and founder of the African Heritage Studies Association in 1969, a time when there was, as he described it, “systematic and racist suppression and distortion of African history by traditional scholars.” He had been aware of this distortion since childhood. I saw no African people in the printed and illustrated Sunday school lessons. I began to suspect at this early age that someone had distorted the image of my people. My long search for the true history of African people the world over began. |

Gerda LernerGerda Lerner (1920–2013) was instrumental in the development of women’s and gender history. She grew up in a Jewish family in Vienna, with the rise of the Nazis and Spanish fascists instilling anti-fascist sentiments in her at an early age. After the Anschluss in March 1938, Lerner and her mother were arrested and spent six weeks imprisoned — an experience that had a formative influence in her life. A young and radical Lerner arrived in the U.S. in 1939, where she quickly started writing journalism and screenplays. She soon became a national leader in the Congress of American Women (CAW), where she worked with poor Black women and began to understand the limitations of her own middle-class assumptions. While McCarthyism led Lerner to hide her Communist leanings, she remained active, helping to form the National Organization for Women (NOW). Lerner earned a Ph.D. at Columbia University, where her dissertation about the white abolitionist Grimke sisters — antislavery activists of their era as well as early women’s-rights advocates — was soon published as a book. Her 1972 book, Black Women in White America, perhaps her most influential work, was one of the first to detail the lives of African American women. Lerner went on to teach women’s history at Sarah Lawrence College, working and writing continuously for the rest of her life. Learn more about Gerda Lerner. |

|

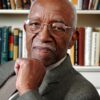

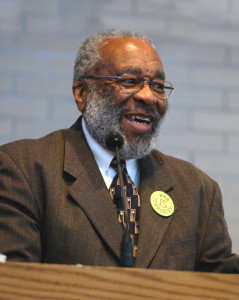

Lerone Bennett Jr.Historian Lerone Bennett Jr. (1928–2018) has written articles, poems, short stories, and numerous books on African American history. After attending public schools in Jackson, Mississippi, Bennett attended Morehouse College and Atlanta University before moving to Chicago in 1952 to be city editor for JET magazine. Bennett quickly became senior editor at Ebony. In his first book, Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America, 1619-1962, Bennett described the long history of Black slavery and racial segregation. In 1964, Bennett wrote the first biography of Morehouse College classmate, Martin Luther King Jr. Bennett’s many honors include the Literature Award of the Academy of Arts and Letters and the Book of the Year Award from the Capital Press Club. He also served as an advisor and consultant to the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) in 1967. Learn more about Bennett from his biography, Our Kind of Historian. |

|

|

Gwendolyn Midlo HallGwendolyn Midlo Hall (1929–2022) was a historian, educator, and author who focused on the history of slavery in the Caribbean, Latin America, and the African Diaspora in the Americas. She authored numerous books, adding to scholarly understanding of the diverse origins of cultures throughout the Americas. Hall also created a database of records identifying and describing more than 100,000 enslaved Africans. It has become a primary resource for historical and genealogical research. Hall was also Professor Emerita of Latin American and Caribbean History at Rutgers University in New Jersey, where she taught for 25 years. Learn more about her life in her memoir, Haunted by Slavery: A Memoir of a Southern White Woman in the Freedom Struggle. |

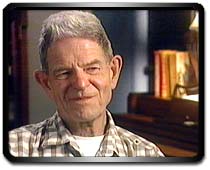

Staughton LyndStaughton Lynd (1929–) has been an activist, historian, author, lawyer, and radical his entire life. In the early 1960s, Lynd taught history at Spelman College alongside Howard Zinn. He was active in the Civil Rights Movement and helped direct the Mississippi Freedom Schools in 1964. In 1965, with Tom Hayden and Herbert Aptheker, Lynd made a controversial trip to Hanoi, hoping to clarify the peace terms of the Vietnamese government and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. His involvement in the anti-war movement led to his being denied the right to teach history, so in the 1970s Lynd went to law school. He has dedicated his life to labor and prison issues. Learn more about Lynd in this article at the Zinn Education Project. |

|

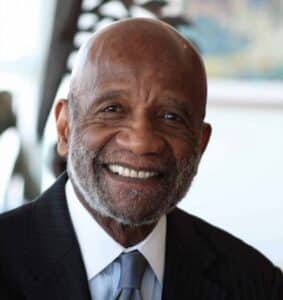

Vincent HardingVincent Harding (1931–2014) was an author, civil rights activist, and theologian. Harding grew up in Harlem and became the first African American editor of the college newspaper at the City College of New York. Harding was active in the Civil Rights Movement in the south during the 1960s and was the first director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center in Atlanta, Georgia. In addition to writing numerous books, Harding also taught at Spelman College, was an advisor for the documentary Eyes on the Prize, and was the founder of the Veterans for Hope Project. Learn more about Harding at the Zinn Education Project. |

|

Rodolfo AcuñaAccording to the Rodolfo Acuña (1932–) website, Acuña was the founding chair of the Chicana/o Studies department at then San Fernando Valley State (California State University at Northridge) — the largest Chicana/o Studies Department in the United States. He has written numerous books, three of which received the Gustavus Myers Award for the Outstanding Book on Race Relations in North America. Among his many awards, Acuña has received the National Hispanic Institute Lifetime Achievement Award, a Life Time Achievement Award from the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, and the Distinguished Scholar Award from the National Association for Chicano Studies, among others. Black Issues in Higher Education selected Acuña one of the “100 Most Influential Educators of the 20th Century.” Acuña has also published three children’s books and more than 200 academic and public articles, in addition to over 160 book reviews in academic journals. Learn more about Acuña here. |

|

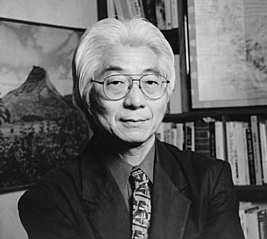

Ronald Toshiyuki TakakiRonald Toshiyuki Takaki (1939–2009) was the author and editor of more than 20 books, including Iron Cages: Race and Culture in 19th Century America (1979), Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (1989), A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America (1993) and Double Victory: A Multicultural History of America in World War II (2000). He established UC Berkeley‘s PhD program in ethnic studies, the first of its kind in the nation. “Ron Takaki elevated and popularized the study of America’s multiracial past and present like no other scholar, and in doing so had an indelible impact on a generation of students and researchers across the nation and world,” Don T. Nakanishi, director of UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, said. Learn more about Takaki at the Zinn Education Project profile. |

There are many more people’s historians and people’s history storytellers who preceded or were contemporaries of Howard Zinn. Here are just a few others:

| Herbert Aptheker (1915–2003) | Jesse Lemisch (1936–2018) |

| Derrick Bell (1930–2011) | Leon Litwack (1929–2021) |

| Eleanor Flexner (1908–1995) | Milton Meltzer (1915–2009) |

| Eduardo Galeano (1940–2015) | George Rawick (1929–1990) |

| A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. (1928–1998) | Walter Rodney (1942–1980) |

| Nathan I. Huggins (1927–1989) | Alexander Saxton (1919–2012) |

| C. L. R. James (1901–1989) | E. P. Thompson (1924–1993) |

| Francis Jennings (1918–2000) | Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1949–2012) |

| William Loren Katz (1927–2019) | Eric Williams (1911–1981) |

A reminder that these names are just a sampling from hundreds of 20th century people’s historians.

As for contemporary historians — the majority approach their work with a people’s history lens and have expanded and deepened the field in creative ways. We feature some of this work in our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online classes.

To provide feedback on this list, email zep@zinnedproject.org.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn