In Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq, Stephen Kinzer tells the stories of the politicians, spies, military commanders, and business executives who took it upon themselves to depose foreign regimes. He details the three eras of America’s regime-change century — the imperial era, which brought Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Nicaragua, and Honduras under America’s sway; the cold war era, which employed covert action against Iran, Guatemala, South Vietnam, and Chile; and the invasion era, which saw U.S. troops toppling governments in Grenada, Panama, Afghanistan, and Iraq. [Publisher’s description.]

In Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq, Stephen Kinzer tells the stories of the politicians, spies, military commanders, and business executives who took it upon themselves to depose foreign regimes. He details the three eras of America’s regime-change century — the imperial era, which brought Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Nicaragua, and Honduras under America’s sway; the cold war era, which employed covert action against Iran, Guatemala, South Vietnam, and Chile; and the invasion era, which saw U.S. troops toppling governments in Grenada, Panama, Afghanistan, and Iraq. [Publisher’s description.]

ISBN: 9780805082401 | Times Books/Macmillan

Related Resources

Democracy Now! interviews with the author. Part 1. Part 2.

Excerpt from Part 1

AMY GOODMAN: Stephen Kinzer, I want to begin where you do in the book, and that is, with Hawaii.

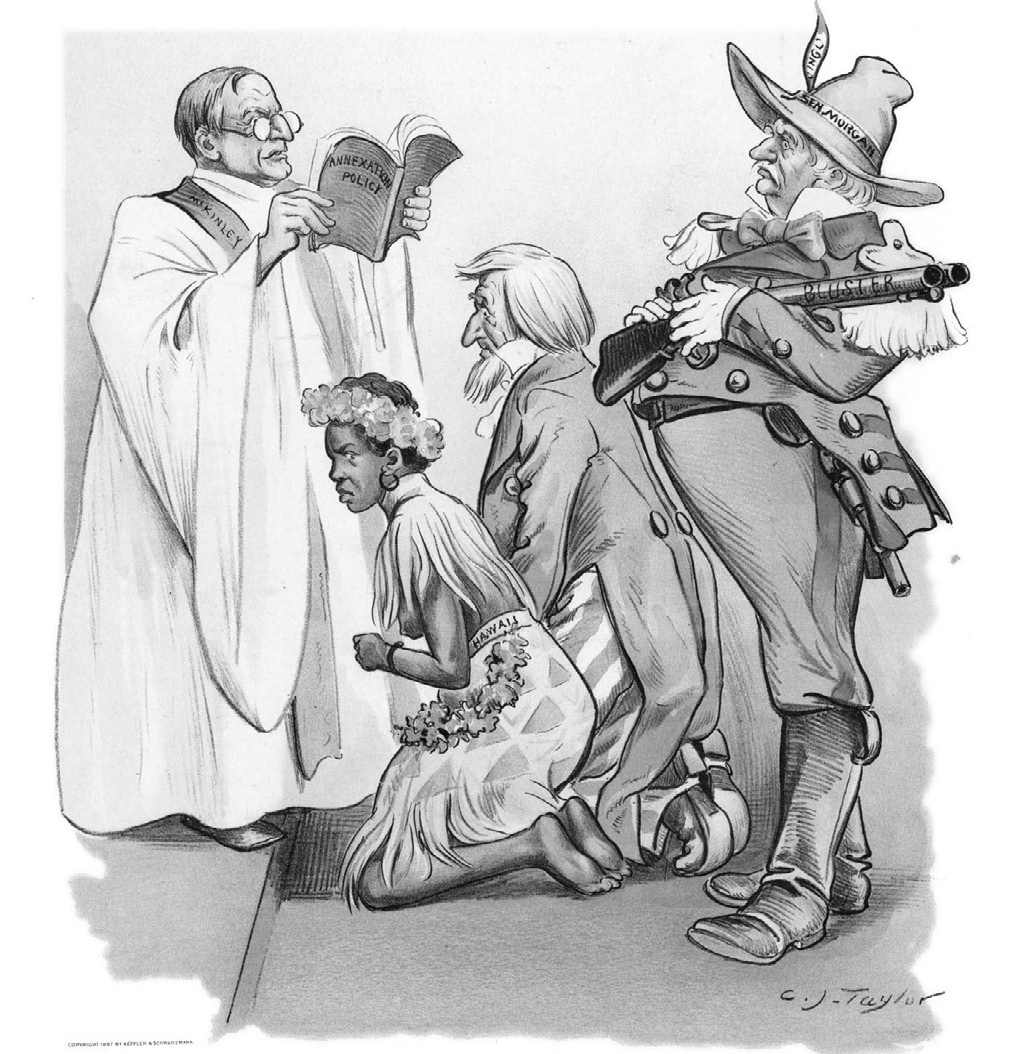

STEPHEN KINZER: Many Americans I don’t think realize that Hawaii was an independent country before it was brought into the United States. In brief, this is the story. In the early part of the 19th century, several hundred American missionaries, most of them from New England, sailed off to what were then called the Sandwich Islands to devote their lives to, as they would have put it, raising up the heathen savages and teaching them the blessings of Christian civilization.

It wasn’t long before many of these missionaries and their sons began to realize that there was a lot of money to be made in Hawaii. The natives had been growing sugar for a long time, but they had never refined it and had never exported it. By dispossessing the natives of most of their land, a group that came from what was then called this missionary planter elite sort of left the path of God, went onto the path of Mammon and established a series of giant sugar plantations in Hawaii, and they became very rich from exporting sugar into the United States.

In the early 1890s, the U.S. passed a tariff that made it impossible for the Hawaiian sugar growers to sell their sugar in the U.S. So they were in a panic. They were about to lose their fortunes. And they asked themselves what they could do to somehow continue to sell their sugar in the U.S.

They came up with a perfect answer: We’ll get into the U.S. How will we do this? Well, the leader of the Hawaiian revolutionaries, if you want to call them that, who were mostly of American origin, actually went to Washington. He met with the Secretary of the Navy. He presented his case directly to the President of the United States, Benjamin Harrison. And he received assurances that the U.S. would support a rebellion against the Hawaiian monarchy.

So he went back to Hawaii and became part of a triumvirate, which essentially carried out the Hawaiian revolution. He was one part of the triumvirate. The second part was the American ambassador, who was himself an annexationist and had been instructed by the State Department to do whatever he could to aid this revolution. And the third figure was the commander of the U.S. naval vessel, which was conveniently anchored right off the shores of Honolulu.

. . . The leader of the Hawaiian revolutionaries, this missionary planter elite, simply announced at a meeting one day, “We have overthrown the government of Hawaii, and we are now the new government.” . . .

AMY GOODMAN: It still took a few years before Hawaii was ultimately annexed.

STEPHEN KINZER: It’s a very interesting story. Immediately after the revolution, the revolutionaries went back to Washington and, sure enough, President Harrison, as he promised, submitted to the U.S. Congress a law to bring Hawaii into the U.S., but there was a great resistance to this when it was understood how the coup was organized and on whose behalf it was organized, so the Congress did not immediately approve the annexation of Hawaii.

And right at that time, the presidency changed. The Republican, Benjamin Harrison, was out of office, and the new president, a Democrat, Grover Cleveland, came in. He was against annexation. He was an anti-imperialist. He withdrew the treaty. And that meant that Hawaii had to become an independent country for a few years, until the next Republican president came into office, McKinley. And then, at the height of the Spanish-American War, when the U.S. was taking the Philippines, Hawaii was presented to the U.S. as a vital midway station between California and the Philippines. And it was at that time, five years after the revolution, that Hawaii was actually brought into the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Stephen Kinzer. So, first came the missionaries, then came the Marines.

STEPHEN KINZER: Yeah, exactly. Sometimes we hear the phrase “Business follows the flag.” But in my research, I found that it’s actually the opposite. First comes the business operations, then comes the flag. It’s the flag that follows business.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn