By Suzanna Kassouf, Matt Reed, Tim Swinehart, Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, and Bill Bigelow

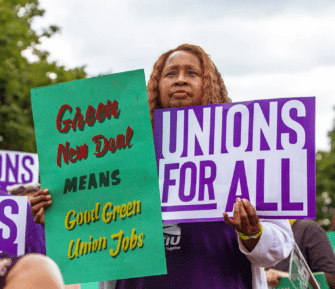

Green New Deal rally in Detroit ahead of the Democratic Party presidential primary debate on July 31, 2019. Source: Becker1999 via Flickr

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change determined that global emissions need to be halved in less than 12 years or we will face catastrophically worsening drought, floods, extreme heat, and incalculable suffering. This fact has been repeated by those in the Climate Justice Movement so many times it can feel like screaming into the void. And yet it must be repeated because it is true and urgent. Slashing global emissions in this decade is a necessity, but it will take enormous pressure from below to demand that transformative policies are enacted by the world’s most powerful governments. We need action and action now.

Terrifying scenarios of a scorching future cannot alone propel us forward. We need to be energized and sustained not only by the harm we seek to prevent, but by the beautiful possibilities on the carbon-free horizon. The brilliance of Molly Crabapple’s and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s short film, A Message from the Future, is that it introduces the Green New Deal as a possible path toward a hopeful and humane future, not just an escape plan from a dystopian one. But to get there — to universal health care, a federal jobs guarantee, a transformed energy infrastructure, and an economy where the labor movement is powerful and care work is predominant — we need action and action now.

As K–12 educators already trying to tackle climate justice in our classrooms, we need no convincing about the wisdom of teaching the Green New Deal (GND). But given that the GND is not a single policy or even platform, but a still-developing vision of transformation, what should that teaching look like? In developing this lesson — part of a suite of lessons we are creating for Rethinking Schools — we were clear that we wanted to invite students to be engaged as architects of that vision, not just observers. We wanted students to be able to make judgments about and share opinions on the collection of policies needed to prevent climate disaster and secure a more just future.

“Green Jobs” by Lisa Vollrath, Creative Action Network poster series.

The GND is ambitious. That makes it easy for protectors of the status quo to dismiss it as impractical, impossible, pie in the sky. Without concrete historical parallels to refer to, we were concerned that our students’ imaginations would fall prey to cynicism or defeatism. So we turned to the obvious place: the original New Deal, from which the GND of course takes its name. It was in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1933 inaugural speech that he accurately described what the people, experiencing the emergency of the Great Depression, expected from him: “action and action now.”

In this lesson, students learn about the ambitious and multifaceted plan of “action and action now” through the stories of a wide variety of people who interacted with New Deal policies. The twenty people students will “meet” include:

- Viola B. Muse, hired as part of the “Negro Unit” of the Federal Writers Project to document the stories of the last living formerly enslaved people in Florida;

- Martina Gangle Curl, an artist hired to paint murals around Oregon by the Federal Art Project;

- Fred Ross, hired by the Farm Security Administration to manage a camp in California for migrant workers fleeing the dust bowl and unemployment;

- James Lowe, hired by the Civilian Conservation Corps to do forestry work in rural Pennsylvania. His story is included in Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement;

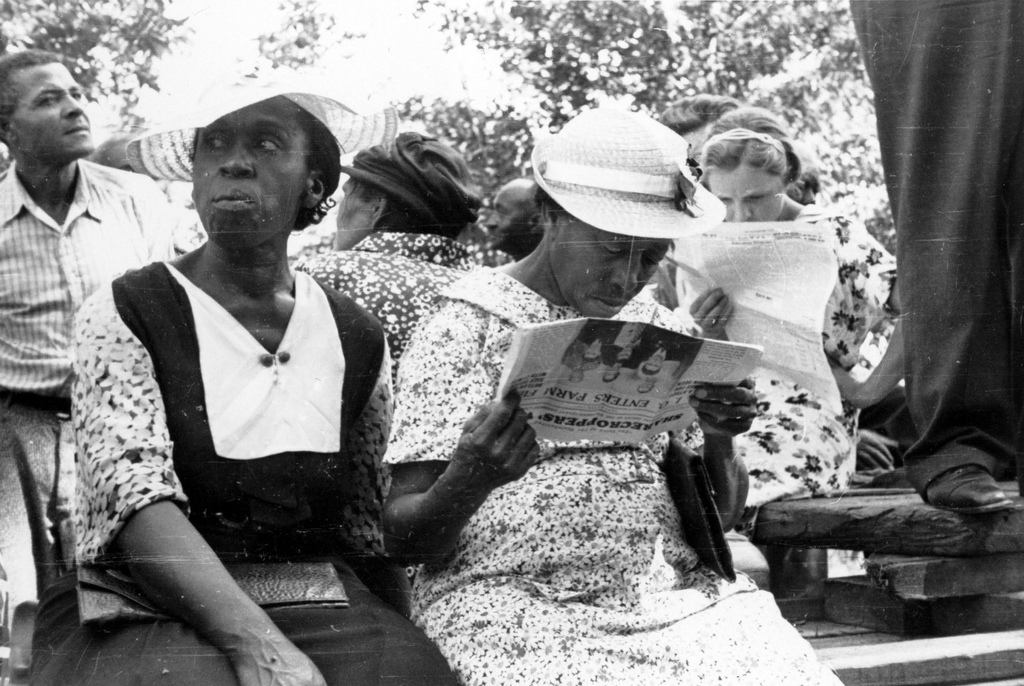

- Emma Tiller, a sharecropper in Texas who benefited from the Works Progress Administration’s jobs program even while criticizing FDR’s agricultural policies;

- Sylvia Woods, union organizer and public speaker, starting at 10-years-old when she refused to sing the “Star Spangled Banner” at school ;

- Louise Stokes, raised two sons who became a congressperson and a mayor, in a public housing unit funded by the New Deal’s Public Works Administration;

- Jesse Jackson, unofficial mayor of the Hooverville encampment in Seattle;

- Ella Baker, labor and civil rights activist, taught in the Workers Education Program;

- Woody Guthrie, a renowned folk musician who composed ballads about labor struggles.

We hoped these glimpses of the New Deal would equip our students, when it came time to talk about the Green New Deal, with historical precedents to dream big, and with plenty of practical ideas about how to transform those dreams into policies.

We hoped these glimpses of the New Deal would equip our students, when it came time to talk about the Green New Deal, with historical precedents to dream big, and with plenty of practical ideas about how to transform those dreams into policies.

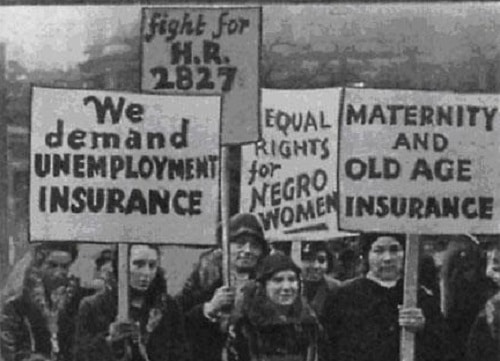

This lesson is not meant to hold up the 1930s as a “When America Was Great” moment. We are clear-eyed about the New Deal: Its housing policies exacerbated and deepened segregation and the racial wealth gap; many of its provisions left out agricultural or domestic workers — and therefore the majority of Black workers in the United States; although the Indian Reorganization Act halted some of the most genocidal policies toward Native people, many other natural resource-related projects — like dam building — ignored treaties and destroyed ways of life; and it was during the New Deal that the Roosevelt administration oversaw the mass deportation of hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

The New Deal, like the country from which it sprang, was poisoned by white supremacy. A number of the roles in the mixer speak to their exclusion from New Deal programs or about its shortcomings.

Read an essay about this lesson “Teaching the Green New Deal: The Prequel” by Suzanna Kassouf, Matt Reed, Tim Swinehart, Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, and Bill Bigelow in Rethinking Schools.

Classroom Stories

In my unit on John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, I’ve found so many of the Zinn Education Project’s resources to be helpful, especially the mixers and roleplays. In conjunction with finishing chapter 21 in the novel, I used the Zinn Education Project’s lesson, “From the New Deal to the Green New Deal.”

I teach English to high school juniors in school in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and this particular mixer was wonderful because it shared the stories of diverse people from across the nation during the struggles of the Great Depression and how the New Deal helped AND hindered them in their quest for survival and dignity.

It also provided our class a nice contemporary connection between the climate crisis that was present during the Dust Bowl years and the even more massive climate crisis we are facing now. Students were able to see those connections and it provided out class an entry point into understanding what the Green New Deal is and how it connects to the first New Deal.

I had a number of students curious to learn more about the Green New Deal after watching the video A Message from the Future, and the activity also allowed us to discuss the Build Back Better Plan currently being weakened in Congress.

In addition to the excellent and detailed description of the lesson provided, I also began our lesson with a freewrite and discussion on the question,

What obligations does a government have towards its citizens? What do you think? What does Steinbeck think?

We then watched “A Message from the Future” and proceeded with the mixer, which by this point my students are familiar with.

As with previous activities from the Zinn Ed Project, the lesson was high interest for students and led to some excellent connections and reflection, a few of which I will share below:

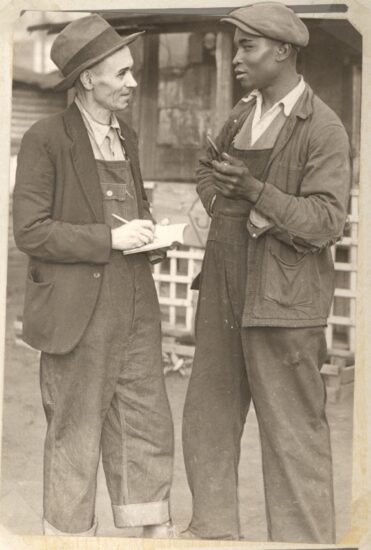

Jesse Jackson, left, the “mayor” of Hooverville, and Ruben Washington make plans to dig ditches to drain water from the streets in the settlement on January 13, 1935. Seattle Times Archive

The story in the mixer that made the biggest impression on me was Jesse Jackson. I think this because he was able to help a lot of people even though the cops were harassing and fighting the community that he made. Something that inspires me about the original New Deal programs is how many people they DID help even if they were closed off to a lot of other people. Some New Deal programs that I would like to see today would be the Federal Art Project for the sole reason that it funds visual art and artists, which I think is very cool.

I think the single best lesson to learn from the New Deal is to listen to the peoples opinion.

Connections I see between the New Deal and what is seen in the Grapes of Wrath is about the American economy, in which these jobs provided a little bit of hope in people’s lives. It’s how the hopes of the Joads is to obtain a job to earn an honest living through work and they take pride in that. People who had benefited from the New Deal benefited in the form of being able to work and backed up by the government and ensuring a degree of financial security.

Ella Baker stood out because she got her degree and it didn´t even help her get a job, when she finally did get a job she help stand up for justice and teach other people to stand up also.

I connected my story — Jesse Jackson’s story — to The Grapes of Wrath as I was the mayor of Hooverville and in the story, the Joads stayed at a Hooverville for a while.

I think the biggest “lesson” from the New Deal that we can learn for thinking about a “Green New Deal” is that we shouldn’t let large corporations run things and cause problems within communities. Some connections I made was Jesse Jackson was harassed by the police, similar to how the Joads were harassed.

If we were to do the green deal again I think we should focus on research related jobs, they promote the economy, have little to no impact on the environment, and you can have a million researchers without any labor leakage. I think the biggest lesson we can learn is that serious projects like these, that promote individual wealth and welfare just work, they simply improve everything around them with little loss in terms of money.

These types of activities, especially the social justice-focused lesson plans created for the Zinn Ed Project, provide opportunities for students to learn about the important, real people who drove the positive changes we’ve seen in our country over its history. It’s a true, “history from below.”

But more than just learning, students begin to empathize and see connections in their own lives and values with people who have been a part of huge, seemingly overwhelming changes. And, it also lets them think about what changes they’d like to see in our own world, and hopefully see that they can be a part of those changes.

Thanks again, Zinn Ed Project!

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn