By Craig Gordon

Back in 2001, I was trying to get my eleventh grade U.S. history class to focus on a passage from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1967 book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? Unfortunately, I was not surprised when a student protested, “We already know about him. We’re tired of hearing about Martin Luther King.”

So I asked, “Okay, what do you know about him?”

“He had a dream,” another student replied as others laughed.

I insisted that there was infinitely more to King and his ideas than one very famous speech. “Well, that’s all they ever show us,” someone complained.

“And that’s why I’m trying to show you something new about him,” I responded, showing — I hope — only a hint of my frustration.

I decided to put together a unit designed to help students penetrate the curtain of clichés and lies the corporate media have erected around Martin Luther King Jr. in order to make him “safe” for public consumption. The bland projection of an image promoting moderate reforms and racial harmony obscures King’s legacy of opposition to capitalist exploitation and violence at home and abroad.

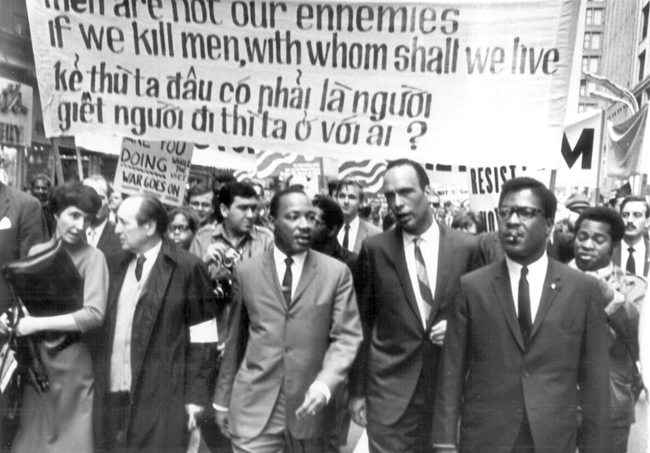

Martin Luther King, Al Raby, and Bernard Lee leading an antiwar demonstration in Chicago on March 21, 1967. Photo by Jo Freeman.

My goal was for my students to be able to explicitly identify the ways in which King is portrayed in the mass media, and specifically, which of his ideas are communicated to the public. I also wanted them to read and discuss a range of King’s ideas that are almost completely unknown to most of the public today and reflect upon why many of King’s ideas introduced in this lesson are almost never referenced in the mass media or in U.S. history textbooks.

For example, like the students in my class, most students have heard about Dr. King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, but they rarely hear about his “Beyond Vietnam,” address given four years later on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York City. At a time when nearly 25 percent of American children live in poverty, King’s words on the extremes of wealth and poverty still resonate today:

“. . . I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

Dr. Martin Luther King speaking against the war in Vietnam at Riverside Church, New York City, April 4, 1967. He was killed one year later.

Many students also don’t know that corporate outsourcing of jobs overseas was also a problem nearly 46 years ago when Dr. King gave this speech. He went on to note:

“. . . A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa, and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say: ‘This is not just.'”

While many of my students have at least some knowledge of the Vietnam War, most have been surprised to learn that King vehemently opposed the war and called the U.S. government “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” Of course, this leads to a discussion of parallels with U.S. militarism in our time.

One student wrote,

“What I didn’t know was what he wanted to do for Vietnam. He said the bulldozers destroyed their areas and the precious trees, poison their water and kill a million acres of crops. He said if ‘we ignore this sobering reality, we will find ourselves organizing [clergy and laymen concerned] committees for the next generation.’ I never heard this whole speech before and I thought it was cool that he wanted to help not just the African Americans but Vietnamese.”

Others were equally surprised that King planned to lead a massive direct action Poor People’s Campaign. One student explained that she “didn’t know that his plan was to ‘mobilize and train thousands of poor and allies to camp out [in front of the White House] with him until they help the poor.’ He planned to group the poor together, no matter the color, race. I didn’t know he wanted unity, well maybe I did, but I didn’t know he fought for the justice of poor people of all color and race.”

Others were equally surprised that King planned to lead a massive direct action Poor People’s Campaign. One student explained that she “didn’t know that his plan was to ‘mobilize and train thousands of poor and allies to camp out [in front of the White House] with him until they help the poor.’ He planned to group the poor together, no matter the color, race. I didn’t know he wanted unity, well maybe I did, but I didn’t know he fought for the justice of poor people of all color and race.”

This student’s closing sentence highlights a key difference between the simplistic racial harmony typically attributed to Dr. King and the militant, multiracial class solidarity he actively organized just before he was murdered.

I have taught a version of this mini-unit every year since developing it, revising it each time based on the previous year’s experience. When I moved to middle school last year I adjusted the pedagogy and content for my eighth graders, who proved to be as receptive to King’s radical vision as my eleventh graders had been. But the administration at my new school objected that “its place in the sequence of the curriculum and its relevance to the content standards is questionable,” since California’s eighth grade U.S. History framework formally concludes in 1914.

The administration apparently hadn’t noticed the explicit connections the lesson — taught during Black History Month — made between struggles against slavery and Native American removal. Or maybe they didn’t think these connections sufficiently justified two days of instructional time in the weeks preceding the state’s high stakes standardized history test.

I cannot justify taking this material out of my curriculum and denying my students what may be their only chance to encounter Martin Luther King’s radical vision that is as relevant now as ever. As one of my students wrote, “We never hear about King’s other ideas because the people in power are afraid that we might try to take up some of King’s ideas and make it a reality.”

Craig Gordon has been a teacher and a union activist in Oakland, Calif. since 1990.

Reprinted from GOOD Magazine (2013) based on a lesson by Craig Gordon on the Oakland Unified School District Urban Dreams website and shared by the Zinn Education Project and Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching.

Related Resources

- Lessons, books, and films for teaching outside the textbook about Dr. Martin Luther King.

- Lessons, books, films, and websites for teaching outside the textbook about the era of the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Classroom Story

I recently stumbled across the Zinn Education Project article There’s Infinitely More to Martin Luther King Jr. Than ‘I Have a Dream’ by Craig Gordon while looking for new ways to talk about MLK. My students complain about seeing the same videos and hearing the same talks every year. The thing that stood out most to me was a student’s quote: “We never hear about King’s other ideas because the people in power are afraid that we might try to take up some of King’s ideas and make it a reality.” Given the current political situation, I think this passage is more true now than ever before.

This article connected me to the lesson A Revolution of Values. Although I did not use this in my mainstream class, we have enrichment and intervention time built in twice a week that students can self select. This short and concise lesson was perfect for the half hour slot and got students to think more broadly about what Martin Luther King Jr. really meant, and his relevance today. Instead of just recalling the line “I have a dream . . .” students actually had to apply his ideals and voice to modern constructs. It is articles and lessons like this, ideas like this, that keep me coming back to ZEP for fresh takes on concepts that have been taught the same way for decades and need new approaches.

Wonderful — thank you!