By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Alex Stegner, Chris Buehler, Angela DiPasquale, and Tom McKenna

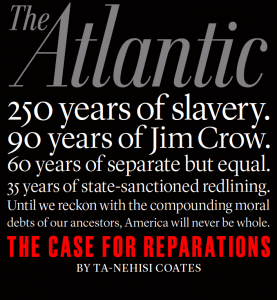

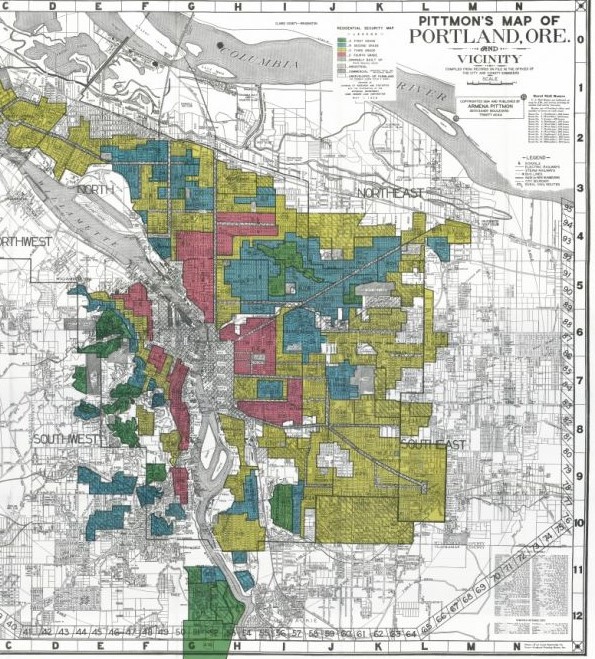

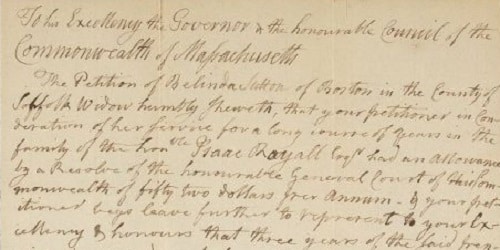

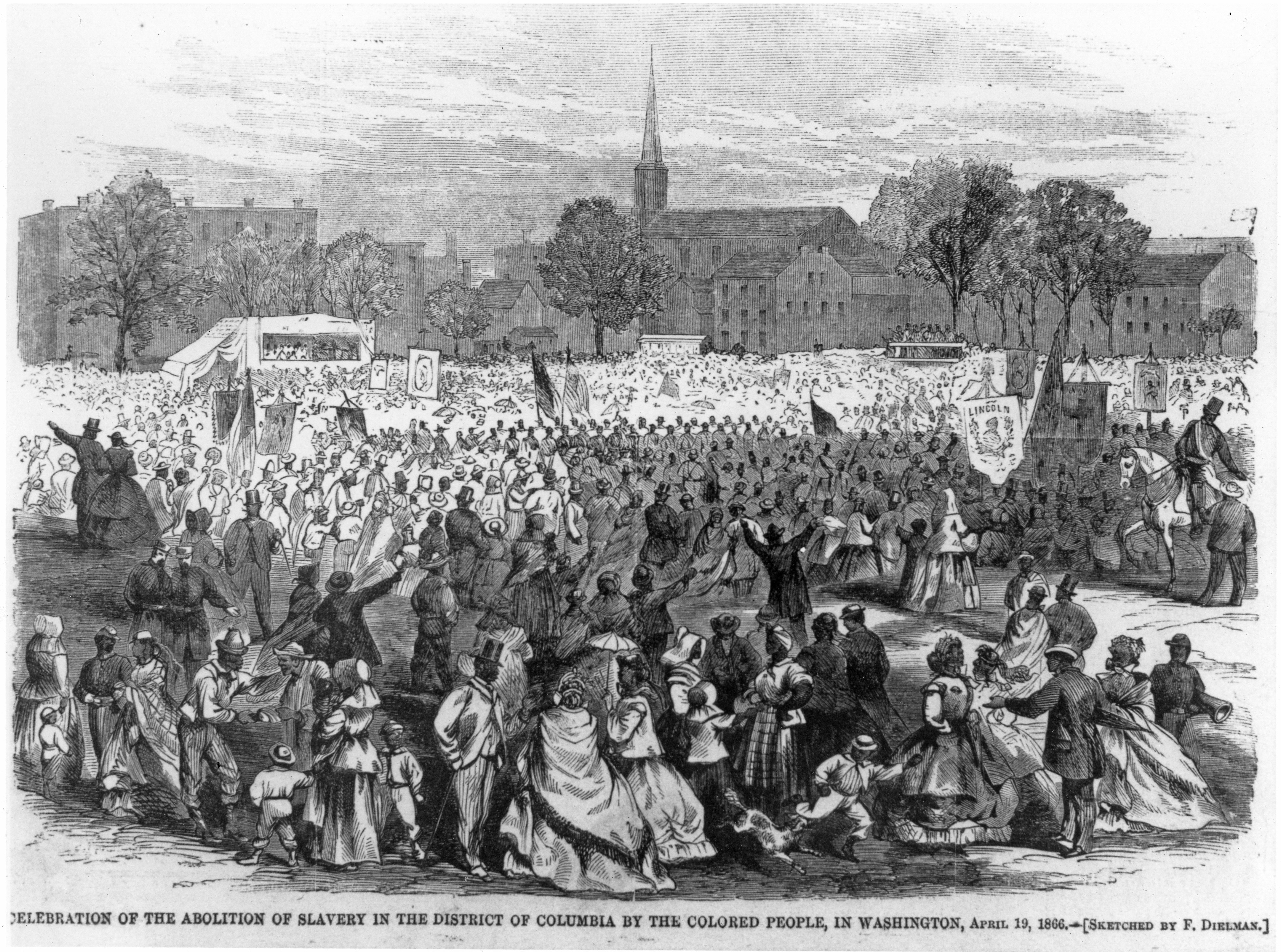

As high school teachers of history and government, we teach about reparations at multiple points across the curriculum. Students learn about the reparations imposed upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles following World War I; students learn about the failure of the U.S. government to enact reparations — 40 acres and a mule — for newly emancipated people during Reconstruction; students learn about the 1988 Civil Liberties Act through which Congress paid 82,000 Japanese American survivors of the U.S. government’s wartime incarceration program $20,000 each, totaling more than $1.6 billion. But when we have asked our students to grapple with the possibility of the United States paying reparations today — for slavery and its 20th- and 21st-century legacies of white supremacist violence, disenfranchisement, and exploitation — we find students struggle to unleash their critical imaginations.

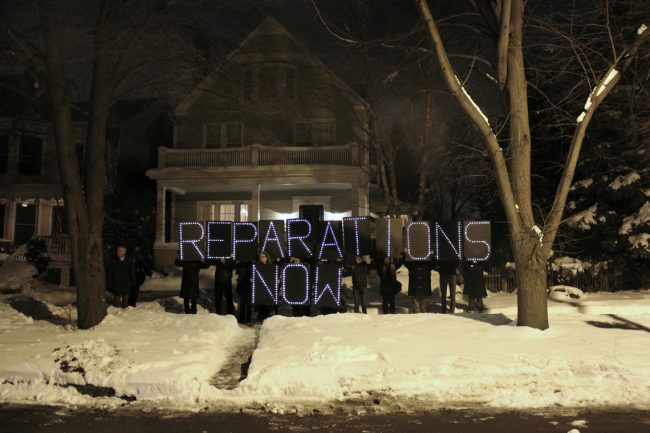

Demanding reparations for police torture, members of the Chicago Light Brigade, Project NIA, and Chicago Torture Justice Memorials protest outside of Rahm Emanuel’s home in 2015. Source: Kelly Hayes.

Some students hold fast to the “slavery is long gone” line of thinking. Some students are frozen by the magnitude of the harm: How could any amount of money ever properly address the wickedness of slavery and racism? Other students worry about the practical questions: Who would be eligible to receive payment? What form would payment take? How long would a reparations program last and how much would it cost? These responses are understandable and important; yet, we noticed that students had trouble navigating through their initial positions to engage with a broader scope of possibilities. Students got stuck thinking of reparations only as a onetime compensatory payment intended to right the wrongs of history.

We developed this lesson to help students find a way into thinking and talking more imaginatively about reparations in general before we ask them to examine the modern debate over African American reparations specifically. [See Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill.] We want students to consider how a legacy of injustice as deeply rooted and multidimensional as anti-Black racism in the United States requires a multifaceted strategy, not a single action.

We developed this lesson to help students find a way into thinking and talking more imaginatively about reparations in general before we ask them to examine the modern debate over African American reparations specifically. [See Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill.] We want students to consider how a legacy of injustice as deeply rooted and multidimensional as anti-Black racism in the United States requires a multifaceted strategy, not a single action.

In this mixer role play, students learn about more than a dozen different examples of reparations — ranging from cash payments to land settlements to state apologies — from a variety of historical moments and places. Students meet those who advocated for reparations, those who received them, and those who did not. They walk away from the activity with a greater understanding of the horizon of possible reparative policies and enough examples to begin to analyze and articulate their own beliefs about the appropriate context, goal, and form of reparations.

Materials Needed

- Mixer roles, cut up, one for every student in the class.

- Blank nametags, enough for every student in the class.

- Copies of Reparations Mixer Questions for every student.

Time Required

- 1–2 90-minute block class periods.

Individual Roles Included

- Judith Jaegermann, from Karlsbad, Czechoslovakia

- Konrad Adenauer, from Cologne, Prussia

- Hubert Kim, a law student

- Maria Rosa Henson, arrested by the Japanese in the Philipines during WWII

- Lee Ok-seon, arrested by the Japanese in Korea during WWII

- Willis Lynch, who was forcibly sterilized by the state of North Carolina

- Dr. Laura Gerald, an employee of the state of North Carolina

- Albert Julkes Jr, son of someone experimented on at the Tuskegee syphilis experiment

- Dr. Vanessa Northington Gamble, a professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, and chairwoman of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee

- Lyman Red Cloud, a member of the Oglala Lakota tribal council

- Emil Notti, from Koyukuk, Alaska

- Toby Obed, who was forcibly sent to a residential school in Canada as a child

- Tony Hall, a former Democratic representative from Ohio

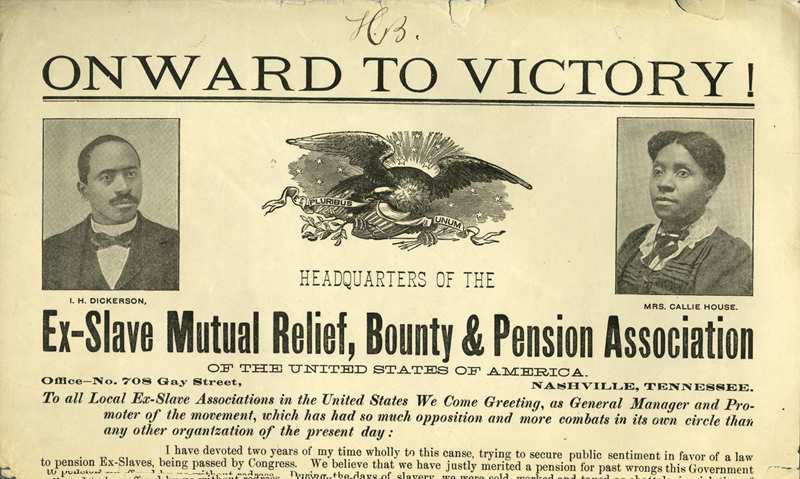

- Callie House, a formerly enslaved person who helped found an the organization National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association

- Queen Mother Moore, who was involved in numerous civil rights organizations and created the Reparations Committee for the

Descendants of American Slaves - Sheila Jackson Lee, a Texas Democrat in the House of Representatives

- William “Sandy” Darity, an economist, researcher, and a professor of public policy at Duke University

- Daniel Akaka, who served in the U.S. Senate for more than 20 years as the first Native Hawaiian senator in United States history

- Dr. David “Keanu” Sai, a political scientist who specializes in Hawaiian constitutionalism and international relations

- Tony deBrum, a representative of the Marshall Islands in negotiations with the United States

- JiJi Jally, from the Marshall Islands, where the United States detonated a nuclear bomb during the Cold War

- Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the first Black African to hold the position of Bishop of Johannesburg and the Archbishop of Cape Town in South Africa

- Ntsiki Biko, the widow of Steve Biko who participated in South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)

- Mzoxolo Sogiba, who was fatally shot by the South African police in Nyanga, in Cape Town

- Gawie Snyders, who is retired and still farms a half-acre plot behind his house in South Africa

- Blanca Katsura, a person of Japanese descent living in Peru when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor

- Masuo Yasui, a Japanese issei living in Oregon when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor

- Min Yasui, the first Japanese American to receive a law degree from the University of Oregon

- Lindsey Smith, who was 17 when he confessed to a murder he did not commit due to torture at the hands of Chicago Police Chief Jon Burge

- Annemarie Cuccia, a freshman at Georgetown University

- Lorraine Jones, of the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Aboriginal People from the Northern Territory of Australia who continues to fight for compensation for stolen land by the British

Classroom Story

My U.S. history class focuses on the essential question of the extent to which we, in the present, have any responsibility or agency to respond to injustices that took place in the past. When we introduce the issue of reparations at the beginning of the semester, students frequently define the concept as “money”, the injustice in question as “racism”, and their opinion as “yes, we owe reparations today” or “no, we do not owe reparations today.”

At the end of the course, having worked through several historical case studies across multiple eras, we return to the question this time using the How to Make Amends mixer lesson. The lesson is highly effective in engaging students in learning, reading, writing, thinking, and speaking about reparations. It moves students seamlessly from personal reflection, to historical analysis and perspective taking, to discourse, and back to reflective writing, this time with a deeper knowledge base and a more sophisticated framework. Students come away with richer understandings that injustice is not limited to “slavery”, that reparations are not limited to “money”, and that informed thinking goes beyond “yes” or “no”.

I teach in an inclusion classroom where students with various abilities, reading levels, and language backgrounds all learn side-by-side. What I appreciate about the How t0 Make Amends lesson is it is a naturally differentiated, collaborative lesson that I can use successfully to support all my students in making progress not only as historical thinkers, readers, and writers but as engaged citizens. They understand that — just as people in the past may have caused injustice, but also may have fought back against it — they have the opportunity and agency in the present to take stands for a more just society.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn