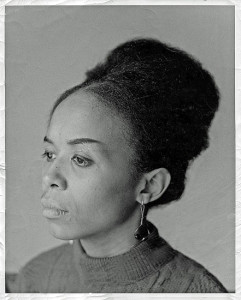

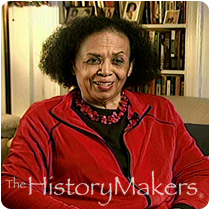

Dorie Ladner, 1968. Photographer: Fred Sweet

At home I had already been instilled with an understanding that I should not bow to anyone. While we learned to respect our elders, my mother told us always to look people in the eye, including white people.

When I was 14, a number of things happened that brought me into the freedom movement. There was the murder of Emmett Till on August 28, 1955. He was just one year older than I was. I was enraged, but I did not know what to do with that anger. His murder made me aware of my blackness.

In the newspapers about the trial I read references to the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. I asked my social studies teacher Mr. Clark what they were about and did not get a satisfactory answer, so I got a copy of the U.S. Constitution. When I read those amendments I felt empowered.

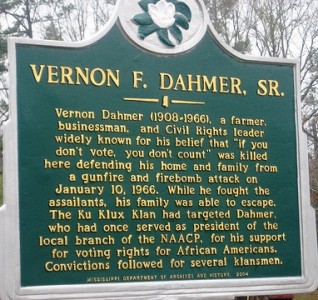

My sister Joyce and I had an opportunity to do something with our anger when Mrs. Beard (sister of renowned local activist Vernon Dahmer) took us to NAACP state meetings in Jackson, Miss. where we met Roy Wilkins, Medgar Evers, and others. I was impressed by Medgar Evers, who was outgoing and showed great warmth toward us. He told us about our rights to better schools and pointed out that our parents were paying taxes for our education.

My sister Joyce and I had an opportunity to do something with our anger when Mrs. Beard (sister of renowned local activist Vernon Dahmer) took us to NAACP state meetings in Jackson, Miss. where we met Roy Wilkins, Medgar Evers, and others. I was impressed by Medgar Evers, who was outgoing and showed great warmth toward us. He told us about our rights to better schools and pointed out that our parents were paying taxes for our education.

After graduating from Earl Travillion High School as salutatorian, alongside her sister, Joyce Ladner, she went on to enroll at Jackson State University. Dedicated to the fight for civil rights, during their freshman year at Jackson State, she and her sister attended state NAACP meetings with Medgar Evers and Eileen Beard.

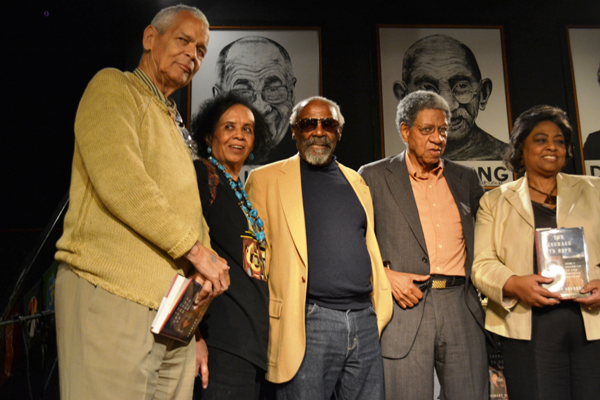

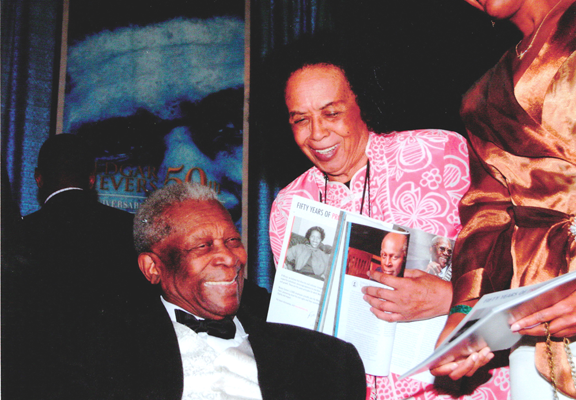

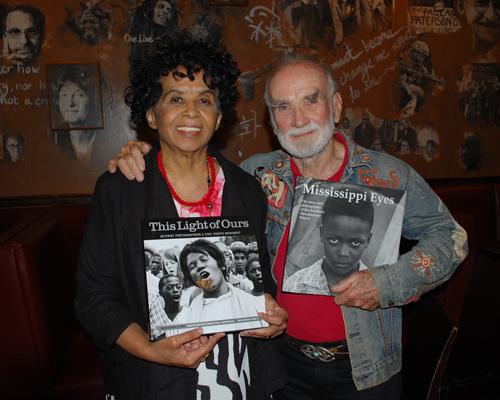

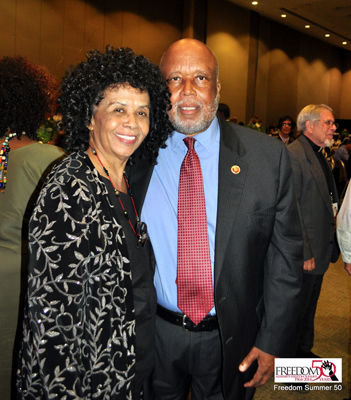

These photos and more can be found in Dorie Ladner’s Flickr album.

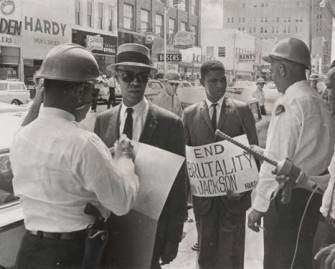

NAACP national secretary Roy Wilkins and Medgar Evers (holding sign) picketing the F. W. Woolworth store in downtown Jackson. Both men were swiftly arrested by local police brandishing electric cattle prods on June 2, 1963, just ten days before Evers’ assassination.

That same year (1961), Ladner was expelled from Jackson State for her support of the Tougaloo Nine, students who were attempting to desegregate the public library.

Ladner enrolled in Tougaloo College to study history and political science. She was inducted into the Gamma Psi Chapter of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority at Tougaloo College in 1961.

Diane Nash with fellow activist Kelly Miller Smith. Source: The Nashville Tennessean

In 1961, Ladner became involved with the Freedom Riders in Jackson, among them Diana Nash, and was thus able to learn her first lessons in nonviolent action. In December 1962, she was arrested for attempting to desegregate a Woolworth’s lunch counter. That same year, she joined with Robert Moses, Mississippi Project director for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and others from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and began working to register disenfranchised black voters and to end racially segregated public accommodations.

Ladner became one of the founding members of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) in Clarksdale, Miss., an umbrella group that included CORE, NAACP, SNCC, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In Indianola, she accompanied Fannie Lou Hamer to register to vote at the courthouse. This resulted in Mrs. Hamer being fired from her job as timekeeper on Marlowe Plantation that same day, although her husband was forced to remain working there, due to their indebtedness under the Reconstruction-era system of sharecropping.

In the spring of 1963, Ladner asked SNCC to send her to Chicago to visit Clyde Kennard, who had been released from jail after a national campaign. “I stayed with Charlie and Sylvia Fisher, who were friends of SNCC. Charlie was director of the packinghouse workers and Sylvia was a schoolteacher. They contributed funds to SNCC and welcomed activists to their mansion in Hyde Park. I had only been out of Mississippi twice so this was a new experience for me living in an integrated setting. The Freedom Singers were there when I arrived. During the time I was there, Lawrence Guyot, Jimmie Travis, and Willie Peacock came up to do fundraising.

Clyde Kennard, Dorie Ladner, and Jimmie Travis. Source: Dorie Ladner

That meeting with Mr. Kennard, I had come full circle from my 9th grade to second year in college. Kennard was dying because Parchman Penitentiary refused to provide him with medical attention or a medical release. He was a political prisoner. Nevertheless, he stood by his beliefs. I felt that if he could stand up, and withstand this, I knew that I could. He was very weak when I saw him, obviously dying. Yet he was peaceful and very calm. He did not reflect any bitterness, any hostility, any malice. He encouraged me to finish my studies and to continue fighting, for what was right, for all mankind. And I assured him I would.

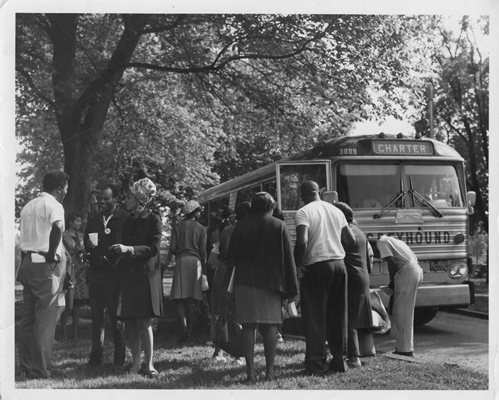

Dorie Ladner at Freedom Summer training in Oxford, Ohio. Source: Herbert Randall, USM

True to her word, Ladner returned to Jackson where she was arrested for her participation in the funeral for Medgar Evers. Evers had been assassinated on June 12, 1963, by white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith, who was not convicted until decades later, and then for violation of Evers’ civil rights.

Ladner was the first woman to join the staff of the Jackson office of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). In 1964, having embraced the concept of recruiting nearly 1,000 volunteers from across the United States, she became a key organizer in the Mississippi Freedom Summer, sponsored by COFO. She worked for SNCC until 1966, guiding the voter registration campaigns of several counties and towns, including Canton, Hinds County, Indianola, Liberty, McComb, and Natchez.

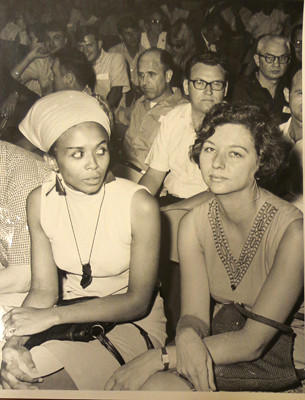

Dorie and Joyce Ladner at the March on Washington, August 23, 1963.

On Jan. 21, 1964, Ladner participated in the Hattiesburg Freedom Day campaign.

Ladner became the SNCC project director in Natchez in 1965, while also lecturing at universities, churches, and other institutions to raise funds. In 1965 in Natchez, she was arrested with Guyot for distributing leaflets about a citizenship class that would teach local people about registering to vote.

Ladner participated in every major civil rights march from 1963 to 1968, including the 1963 March on Washington, the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March, and the 1968 Poor People’s March. She subsequently became an antiwar organizer, working in opposition to the Vietnam War.

Becoming a community organizer for the Human Development Corporation antipoverty program in St. Louis, Missouri, she was an early advocate for civil rights in housing and employment. In 1969–70, Ladner worked to help collect documentation from black participants in the Civil Rights Movement; the papers would later be housed in the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta. She worked in the 1968 presidential campaign of Eugene McCarthy and that of George McGovern in 1972.

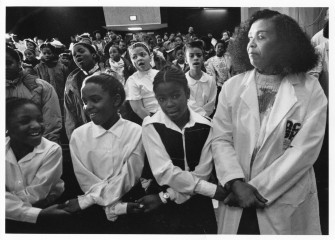

Dorie Ladner, social worker, with D.C. public school students during Negro History Month event at D.C. General Hospital. 1991. Source: Nancy Andrews/Washington Post

In 1970, Ladner became a lay community social worker for the Southside Community Mental Health Center, Atlanta. In 1973, after marriage and the birth of her only child, Yodit, Ladner finally earned her BA degree from Tougaloo College. In 1974, having moved to Washington, D.C., she enrolled in the Howard University School of Social Work, where in 1975 she earned her master’s degree. For 28 years, Ladner was a licensed independent clinical social worker (LICSW) in the emergency room of D.C. General Hospital. She provided supportive intervention and counseling to emergency room patients. She worked in collaboration with many groups, including schools, the Fire Department, and the Rape Crisis Center. Ladner was trained in Critical Incidence Stress Debriefing (CISD) at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as required for ER staff.

McComb student TyKesha Faust speaks with Dorie Ladner about her memories of registering voters in McComb, Miss., in the 1960s. Source: Victor Holt, June 2012

After D.C. General Hospital closed in 2000, Ladner went to work for the District of Columbia’s mental health program, working with patients who had multiple diagnoses of mental illness, including comorbid substance drug abuse. (In retirement, she was a licensed graduate social worker.)

Ladner is featured in the award-winning documentary film Standing on My Sisters’ Shoulders (2002). The women in the film were honored at the Kennedy Center. In 2011, Ladner received the Fannie Lou Hamer National Institute on Citizenship and Democracy Humanitarian Award.

Honorary Degree

On May 18, 2014, Ladner was awarded an honorary doctorate from Tougaloo College at the Commencement Ceremony.

Ladner participated in genealogical research, public speaking, antiwar activities (including against the war in Iraq), and volunteered in the presidential campaign of Barack Obama. Until her death in 2024, she continued organizing as a social and political activist against U.S. wars of aggression and was actively engaged in mobilization for a just U.S. policy in the Middle East. Ladner traveled across the country speaking about the people’s history of the Civil Rights Movement and contemporary social justice issues.

Reflections

Occassionally Ms. Ladner would call the Teaching for Change office to share reflections to post on Facebook, including those below.

Tribute to Jesse Harris, February 6, 2015

(1) Joy Reagon and Jessie Harris, (2) Peggy Dammond and Sam Block, (3) Dorie Ladner (center) (c) Danny Lyon, Nashville, 1962.

Dorie Ladner read the following statement read at Jesse Harris’s funeral.

Jesse Harris’s death has shaken a part of me. We were very close. He was one of the first people I worked with in Mississippi. We were both from Mississippi and started working with Robert Parris Moses around the same time. He taught me about the brutality of Mississippi when he described how he had been beaten and tortured at the Hinds County Work Farm. He was placed in a torture chamber until he passed out from the heat. Then they would bring him out, revive him, and put him back in.

There was many a time that I and others would be travelling all over Mississippi, with Jesse driving the car. We would face fierce danger, yet somehow he would always drive in such a way that we would arrive safely.

He was a kind and generous person. I saw him in June at the Mississippi Freedom Summer 50th gathering. We had a wonderful time talking about our days in the struggle. I will continue to lift up his name in my speeches, as I did recently in a talk about Freedom Summer in New York. Jesse, I will continue to lift up your name.”

Vernon Dahmer, Jan. 10, 2020

Online Interviews and Presentations

Dorie Ladner was featured in a 2017 Black History Month segment on “Full Frontal with Samantha Bee.” See the five minute segment, “We’re Still Not There: A Practical Guide to Resistance.”

Free Lunch Podcast: “Freedom Summer: The Dorie Ladner Interview”

The History Makers The History MakersRead biography from a 2008 interview here. |

Library of Congress Library of CongressInterview with Joyce and Dorie Ladner in conjunction with NMAAHC, 2011. View online. |

Clyde Kennard Event Clyde Kennard EventLadner was one of the featured speakers at the Clyde Kennard portrait unveiling. Read more. |

Jackson Free Press Jackson Free Press“Keep on Pushing: Fifty Years After Freedom Summer, Two Mississippi Sisters Press the Fight for Voting Rights.” Read online. |

Black Power Remembered with Ms. Dorie Ladner Black Power Remembered with Ms. Dorie LadnerLadner shares some of her experience working with Walter Rodney, SNCC, her concept of Black Power, and more. Listen online. |

Profile of Dorie Ladner on the SNCC Digital Gateway. |

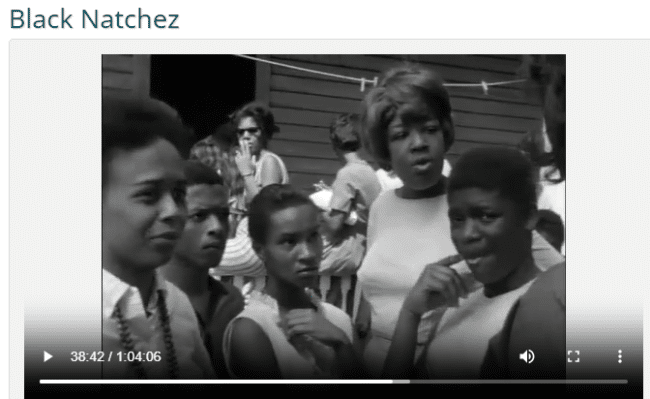

Black Natchez

Dorie Ladner appears in this unique footage about organizing in Natchez. Here is the description from the Tulane Libraries website: Black Natchez (1967) charts early attempts to organize and register Black voters and the formation of a self defense group in the Black community. In 1965, filmmaker Ed Pincus and David Neuman spent ten weeks in Natchez, Mississippi, filming the lives of ordinary people with unedited coverage of public and private civil rights organizational meetings, street demonstrations, and contests of power between young militants and the old guard, as well as secret meetings of African American self-defense organizations and interaction among the Black community. Black Natchez is a digital collection created by the Amistad Research Center. It is presented in the Tulane University Digital Library through a partnership between the Amistad Research Center and Tulane University.

More Articles

What Washington’s African-American museum means to Black Americans (9/23/2016)

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn