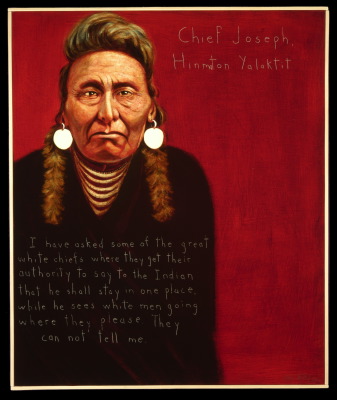

“I have asked some of the great white chiefs where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in one place, while he sees white men going where they please.”

The following biography of Chief Joseph Hinmton Yalaktit is from the Americans Who Tell the Truth website, which features this painting/poster and many more by artist Robert Shetterly.

Son of a Nez Percé Indian chief, Joseph was born Hinmaton Yalaktit (“Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain”) in what is now northeastern Oregon. He became known as Joseph the Younger because his father, one of the first Nez Percé to convert to Christianity, earlier had taken Joseph as his baptismal name.

In 1863, however, following a gold rush by whites in the area, the federal government repossessed some six million acres of tribal land, and Joseph the Elder renounced both the U.S. and Christianity. When he died in 1871, his son became chief and soon had to deal with a very difficult choice.

When a U.S. general threatened a cavalry attack in 1877, Chief Joseph at first agreed to take his people to a reservation in Idaho, now diminished in size by 90%. Before this could happen, however, a group of young Nez Percé warriors attacked white settlements along the Salmon River, and then came to hide among the tribe. Joseph, who initially had believed that resistance to the U.S. military would be futile, now was forced to fight. Moving north through the mountains of Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, the Nez Percé under his leadership conducted one of the most brilliant retreats in American history. In three months this band of 700, with fewer than 200 warriors, traveled almost 1,500 miles while fighting off a pursuing army of 2,000.

By the time the exhausted, starving Nez Percé were forced to surrender in early October 1877, just 42 miles from the Canadian border, Joseph had become famous, and was called “The Red Napoleon.” In truth, his younger brother Olikut and others were the war leaders of their tribe, while he was responsible for guarding the camp. Chief Joseph, however, is best remembered today for his elegant surrender speech, which has been called the most famous statement in American Indian history. It ends, “Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

Chief Joseph had been told that his people would be returned to their lands in Oregon, but instead they were transported to eastern Kansas, and then Oklahoma, where many died from epidemic diseases. He continued to protest their treatment, even traveling to Washington, D.C. in 1879 to meet with President Hayes, but he and the Nez Percé were never permitted to return to their homeland. He died in northeastern Washington State in 1904, and was buried there in exile.

On a visit to Washington, D.C., 1879, Chief Joseph wrote:

“At last I was granted permission to come to Washington and bring my friend Yellow Bull and our interpreter with me. I am glad I came. I have shaken hands with a good many friends, but there are some things I want to know which no one seems able to explain. I cannot understand how the Government sends a man out to fight us, as it did General Miles, and then breaks his word. Such a government has something wrong about it. I cannot understand why so many chiefs are allowed to talk so many different ways, and promise so many different things. I have seen the Great Father Chief [President Hayes]; the Next Great Chief [Secretary of the Interior]; the Commissioner Chief; the Law Chief; and many other law chiefs [Congressmen] and they all say they are my friends, and that I shall have justice, but while all their mouths talk right I do not understand why nothing is done for my people.

“I have heard talk and talk but nothing is done. Good words do not last long unless they amount to something. Words do not pay for my dead people. They do not pay for my country now overrun by white men. They do not protect my father’s grave. They do not pay for my horses and cattle. Good words do not give me back my children. Good words will not make good the promise of your war chief, General Miles. Good words will not give my people a home where they can live in peace and take care of themselves. I am tired of talk that comes to nothing. It makes my heart sick when I remember all the good words and all the broken promises. There has been too much talking by men who had no right to talk. Too many misinterpretations have been made; too many misunderstandings have come up between the white men and the Indians. If the white man wants to live in peace with the Indian he can live in peace. There need be no trouble. Treat all men alike. Give them the same laws. Give them all an even chance to live and grow. All men were made by the same Great Spirit Chief. They are all brothers.

“The earth is the mother of all people, and all people should have equal rights upon it. You might as well expect all rivers to run backward as that any man who was born a free man should be contented penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases. If you tie a horse to a stake, do you expect he will grow fat? If you pen an Indian up on a small spot of earth and compel him to stay there, he will not be contented nor will he grow and prosper. I have asked some of the Great White Chiefs where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in one place, while he sees white men going where they please. They cannot tell me.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn