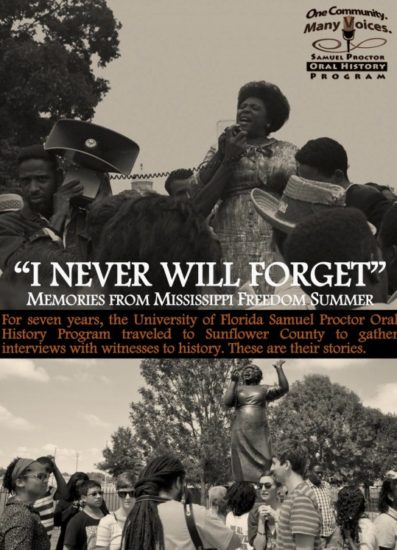

“I Never Will Forget”: Memories from Mississippi Freedom Summer is a collection of interviews conducted by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program over seven years in Sunflower County, Mississippi. Selected in collaboration with the Sunflower County Civil Rights Organization, the stories provide a powerful first person introduction to the history of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement.

“I Never Will Forget”: Memories from Mississippi Freedom Summer is a collection of interviews conducted by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program over seven years in Sunflower County, Mississippi. Selected in collaboration with the Sunflower County Civil Rights Organization, the stories provide a powerful first person introduction to the history of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement.

The oral histories are organized in response to these topics:

- The Most Southern Place on Earth

- Poverty and the Plantation

- Designing a Freedom Summer

- The Sunflower County Movement

- Mass Meetings and Freedom Songs

- One Man, One Vote

- The Fight for Educational Equity

- The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

- The Deadly Seriousness of Mississippi

- “I Never Will Forget”

Published by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program

Excerpt from Introduction

The introduction to the collection places Freedom Summer in the context of the long history of resistance in Mississippi. Here is an excerpt:

MFDP State Convention in Jackson, MS, 1964. (Wisconsin Historical Society.)

The Black Freedom Struggle in the Mississippi Delta is older than slavery, as epic as the Homeric Classics, and as enduring as the Mississippi River. Black Mississippians have created one of the most remarkable chronicles of resistance in United States history. Hitherto hidden from view to all but the most perceptive outsiders, the struggle was unveiled in the year of Freedom Summer as well as in the creation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, the most important independent political party in American history.

To understand the origins of Freedom Summer it is necessary to go back over a century in time before 1964. There are far too many origin stories to tell in this brief space but here are a few. The role that African American soldiers from Mississippi played in the Civil War was decisive in winning the war and preserving the Union. Union Army soldiers of Lieb’s African Brigade saved General Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign on June 7, 1863 by engaging in the longest bayonet engagement of the Civil War at the Battle of Milliken’s Bend. In defeating a Confederate force that had the advantage of numbers and better equipment, black soldiers vindicated Abraham Lincoln’s emancipation policy as a war measure and struck a fatal blow against the power of antebellum planters in Mississippi. Many of these troops had been slaves in the Delta region only weeks earlier. The record of black Mississipians in the struggle for freedom in the Civil War is a story that needs a fuller accounting.

Hiram Rhodes Revels

Black Union Army victories translated into political and economic advancement during Reconstruction. African Americans supported US Senators Blanche K. Bruce and Hiram Revels as well as John R. Lynch, the first black speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives. At the same time however, gains in politics and black self-assertion were tenuous. Born in 1904, Tarboro, North Carolina physician Dr. Milton Quigless shared with me the ordeal of the Page family. The Pages owned a plantation near Port Gibson, Mississippi that drew the ire of whites jealous of an African American family in possession of 600 acres of land. “One particular Page, his name was Hamp Page. He’s a bad man. He says, “Don’t fool with me. I ain’t going to bother you, but if you fool with me, I’m going to get back at you.” And he practiced marksmanship. Threw a dime up; hit it with his pistol. You never see that dime any more. He was that damn good. So one day, when he was in town, Port Gibson, the Page plantation was just about eight or nine miles from Port Gibson. One of them [Pages] had a run in with a white man and the white man slapped him. So he beat the hell out of that white man.” After a heated gun battle, the Pages were driven out of Clairborne Parish and fled to St. Louis.

Like their counterparts across the South, white planters engaged in a wave of terror and legal chicanery to disenfranchise African Americans in order to institute a system of economic peonage and agricultural profits. The Vicksburg Massacre cost 300 African American lives in 1874, and the vaunted “Second Mississippi Plan” served as a model of voter suppression throughout the South and a guarantor of legal segregation for decades.

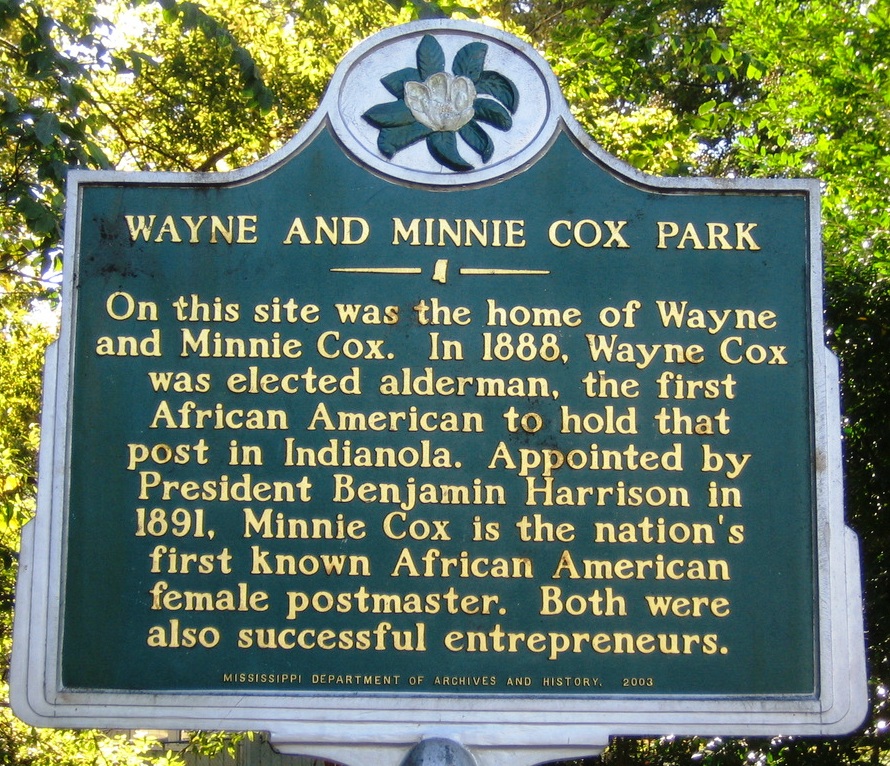

Black resistance persisted. While U.J.N. Blue of Meridian urged black Mississipians to leave for Africa in 1895 in order to escape white repression, Minnie Cox, the heroic black female postmaster of Indianola stood strong against white terrorists in 1903-1904 before finally ceding her position to save her family. During World War I, African Americans voted with their feet and left the state by the tens of thousands to seek better lives in the North in spite of draconian efforts by planters to force them to stay. “Because Rev. Thomas Collins read colored newspapers when ordered not to,” the Afro-American newspaper reported in 1919, “[A]nd because he persuaded his congregation not to attend an address by a speaker who was booked to advise colored people to stay in the South, Rev. Thomas Collins, of Yazoo, Mississippi narrowly escaped a severe beating from the Klan . . . On the way to the whipping post, Rev. Collins escaped and walked fifty miles to Jackson, Mississippi where he took the train for Philadelphia.” African Americans also organized against the threat of lynching. A “racial clash seems imminent late tonight” the Montgomery Advertiser reported on February, 1911 “as a result of a shotgun and pistol battel [sic] earlier in the evening between a posse of white men and a crowd of negroes. The shooting was an attempt on the part of the posse to disperse a gathering of Negroes in a house on the outskirts of Gunniston.” An anonymous letter writer warned the editor of the Belzoni newspaper in the spring of 1919 that whites would begin to suffer accordingly if they continued to engage in anti-black violence. In Vicksburg that same year, “Officials here have received many threats that the Negroes of this section intend to start riots here to kill white people in retaliation for the lynching and burning of a colored man here recently. Much uneasiness has been caused, the officials apprehend not trouble. No chances have been taken, however, for with big crowds here ,the police force has been doubled, deputies are on duty, no fire arms are being sold, the cross river saloons are closed and the jail has been converted into an arsenal.”

Black resistance persisted. While U.J.N. Blue of Meridian urged black Mississipians to leave for Africa in 1895 in order to escape white repression, Minnie Cox, the heroic black female postmaster of Indianola stood strong against white terrorists in 1903-1904 before finally ceding her position to save her family. During World War I, African Americans voted with their feet and left the state by the tens of thousands to seek better lives in the North in spite of draconian efforts by planters to force them to stay. “Because Rev. Thomas Collins read colored newspapers when ordered not to,” the Afro-American newspaper reported in 1919, “[A]nd because he persuaded his congregation not to attend an address by a speaker who was booked to advise colored people to stay in the South, Rev. Thomas Collins, of Yazoo, Mississippi narrowly escaped a severe beating from the Klan . . . On the way to the whipping post, Rev. Collins escaped and walked fifty miles to Jackson, Mississippi where he took the train for Philadelphia.” African Americans also organized against the threat of lynching. A “racial clash seems imminent late tonight” the Montgomery Advertiser reported on February, 1911 “as a result of a shotgun and pistol battel [sic] earlier in the evening between a posse of white men and a crowd of negroes. The shooting was an attempt on the part of the posse to disperse a gathering of Negroes in a house on the outskirts of Gunniston.” An anonymous letter writer warned the editor of the Belzoni newspaper in the spring of 1919 that whites would begin to suffer accordingly if they continued to engage in anti-black violence. In Vicksburg that same year, “Officials here have received many threats that the Negroes of this section intend to start riots here to kill white people in retaliation for the lynching and burning of a colored man here recently. Much uneasiness has been caused, the officials apprehend not trouble. No chances have been taken, however, for with big crowds here ,the police force has been doubled, deputies are on duty, no fire arms are being sold, the cross river saloons are closed and the jail has been converted into an arsenal.”

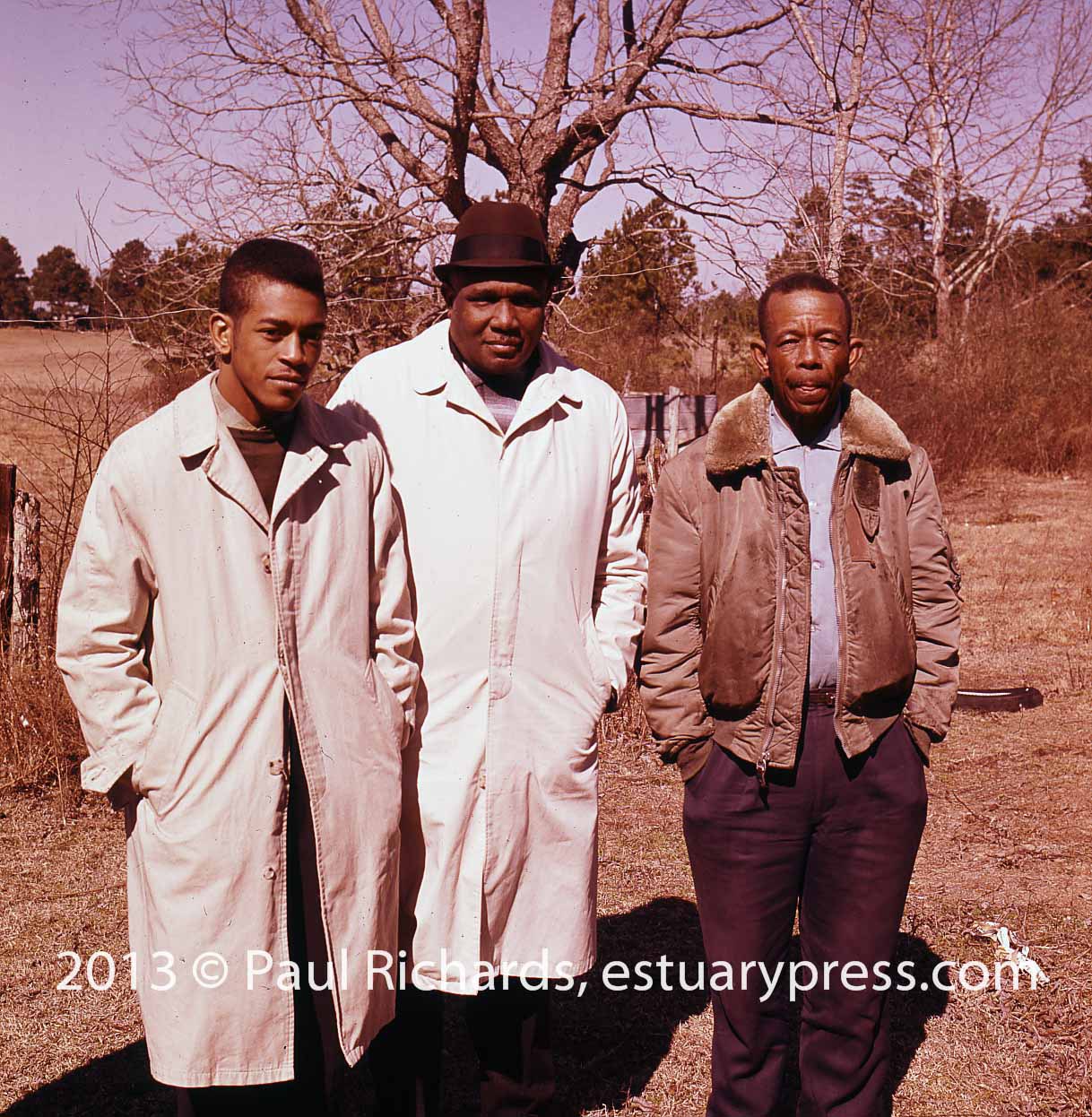

Hollis Watkins, Amzie Moore, E.W. Steptoe, Mississippi, 1963. Photo by Harvey Richards.

Thanks to the testimony of African Americans and the scholarship of historians including, Emilye Crosby, John Dittmer, Todd Moye, Charles Payne, Akinyele Umoja, and others, we now know that black Mississippians had been preparing the foundations of Freedom Summer for decades. Black World War II veterans, including Medgar Evers, attempted to vote shortly after the end of the war. Amzie Moore was leading voter registration campaigns in 1957 in Bolivar County. In 1961, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized voter registration schools in McComb. That fall, Burgland High School students organized protests in solidarity with fellow student Brenda Travis, then 15-years-old, who had engaged in an act of resistance against segregation at the local Greyhound Bus Station lunch counter. The road to Freedom Summer was not a straight and easy path; it was more like water on the rock paid for by the blood sweat and tears of countless black Mississippians.

The stories that you will read in this book represent generations of struggle. These are excerpts of the 130+ oral histories that we have conducted over the past several years based on themes chosen in collaboration with Dr. Stacy White and the Sunflower County Civil Rights Organization. There are many tragedies and sorrow songs in these pages just as there are triumphs and narratives of people discussing the building of solidarity between people of different cultures, regions and racial identities. The record of striving for social justice in these pages is unparalleled in US history. However, we believe that in many ways that we have just begun to chronicle this amazing history. There are many more stories to tell, more archives to unearth, and more public discussions and organization workshops that need to take place in order to figure out “Where do we go from here?”

Paul Ortiz, May 20, 2014

Director, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program

Associate Professor of History, University of Florida

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn