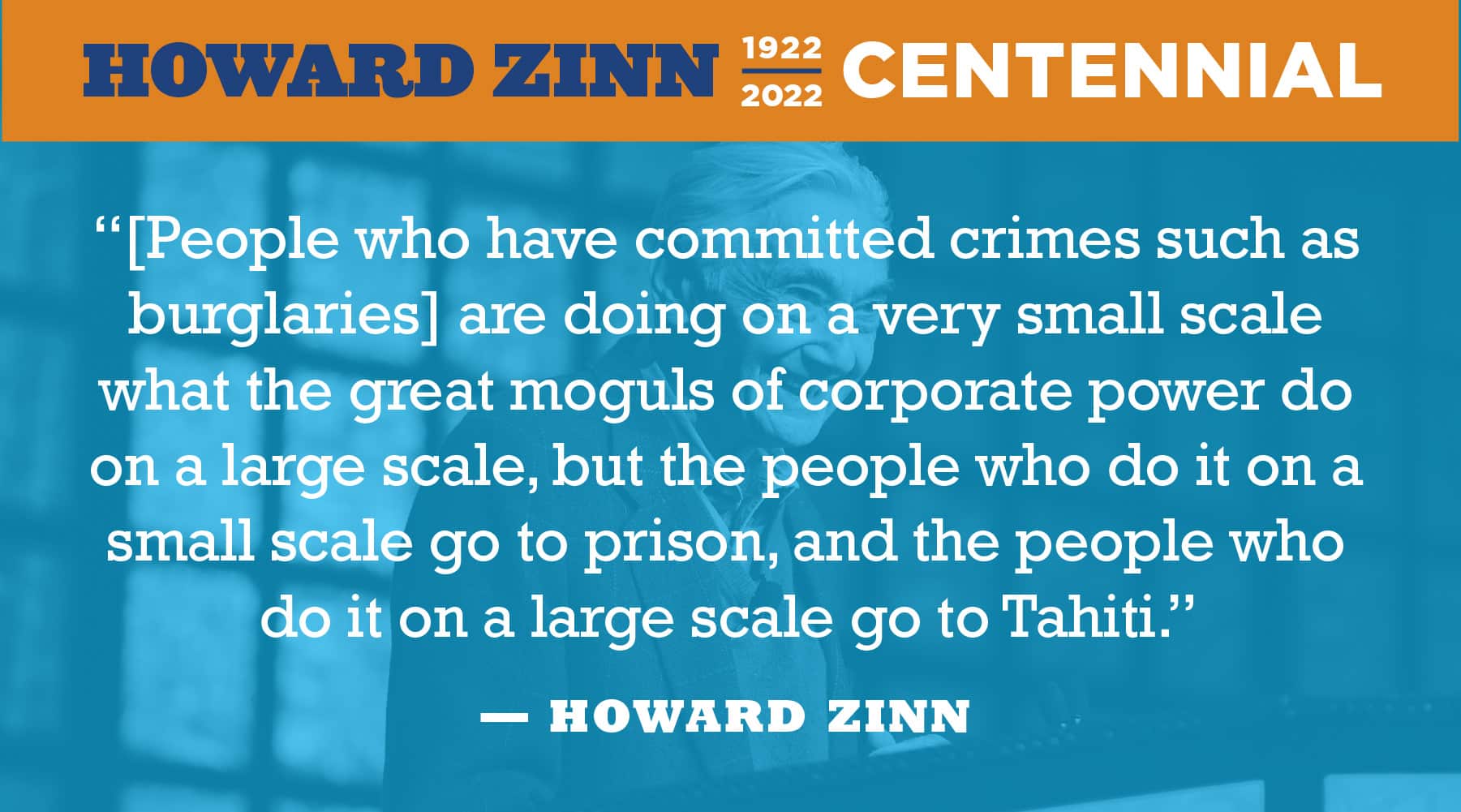

On this 100th anniversary of Howard Zinn, we are highlighting his writing about prisons and his correspondence with prisoners. We begin with an essay called “Solutions” in the chapter on prisons in Justice in Everyday Life: The Way It Really Works, published in 1974.

On this 100th anniversary of Howard Zinn, we are highlighting his writing about prisons and his correspondence with prisoners. We begin with an essay called “Solutions” in the chapter on prisons in Justice in Everyday Life: The Way It Really Works, published in 1974.

In the spirit of prison abolitionists today, Zinn wrote that, “Prisons cannot be reformed, any more than slavery can be reformed. They have to be abolished.”

By Howard Zinn

We must talk about prison reform. But before we do, we should consider carefully what George Bernard Shaw once wrote, in his book The Crime of Imprisonment:

Imprisonment as it exists today is a worse crime than any of those committed by its victims; for no single criminal can be as powerful for evil, or as unrestrained in its exercise, as an organized nation. Therefore, if any person is addressing himself to the perusal of this dreadful subject in the spirit of a philanthropist bent on reforming a necessary and beneficent public institution, I beg him to put it down and go about some other business. It is just such reformers who have in the past made the neglect, oppression, corruption, and physical torture of the old common gaol the pretext for transforming it into that diabolical den of torment, mischief and damnation, the modern model prison.

Prisons cannot be reformed, any more than slavery can be reformed. They have to be abolished. And yet, they will not be abolished until society is changed, until people think differently about punishment, about law, about crime, about violence, about property, about human beings. They will not be abolished until our society works differently: until wealth is equally distributed, and people don’t live in slums, and the motivations for crime and punishment become very weak, and the desire to live cooperatively with other people becomes very strong.

Then are we on a perpetual seesaw, between tiny, deceptive changes, and utopian impossibility? And are we dealing with one of those frustrating puzzles, where every time you get one piece in line, another goes out of line, and there are too many pieces to deal with at once: the frustrations and brutality of the prison guards, the violence of the prisoners, the complacency of the public, the caution of politicians?

We have to begin. And the only way to begin is from below, with the prisoners themselves, with their families, their friends, people in the community who begin to care. It is they — we — who need to organize, to resist, to pressure, to demand, to persuade, to jolt people into new ways of thinking by confronting them with the horror and unworkability of prisons, the need to abolish them, and what that means for changing so much else. We need to have immediate reforms, even while we refuse to fool ourselves about how reforms are not enough, how fundamental change is needed.

It has to come from below, because change that comes from the top, from national laws, from legislators, has no staying power unless pushed by an incessant force of those who care most, and who don’t stop. Organized people, at the immediate, local level, who do not get discouraged when they lose, and don’t disband when they win, and who have a long-range view of what is needed — that may be the best solution there is, because there is no perfect one, to the dilemma of petty reform or utopian revolution.

Massachusetts is a leader in prison reform. In October, 1972, a Correctional Reform Act went into effect, providing for prison inspections by the Public Health Department, work-release and study-release programs, furloughs, and other provisions. Even before the act was passed, the state had closed its youth institutions.

But it is the old story of much heralded reform as a spray of chlorine into a poisoned well. Walpole, Norfolk, Concord, Deer Island, the Charles Street Jail, remain very much as they are. The reform Commissioner of Correction, John Boone, wants to make changes, and is harried by the guards, by the politicians, by the whole punishment establishment, by those who oppose him because he is black or because he is a reformer. (As this book is edited, he has just been dismissed by Governor Sargent.) It clearly takes more than one law, more than one man, to end the crime of punishment in Massachusetts, or anywhere else.

The prisoners themselves, their families, their friends, have begun to organize. One day, one hundred and fifty persons marched outside Concord Prison to support the demands of inmates. Through the first months of 1973, citizens stayed inside Walpole for twenty-four hours a day, on three eight-hour shifts, to create a kindlier atmosphere, to try to make sure terrible things did not happen.

At the heart of this process of change were the prisoners themselves, affected in some indescribable way these past years by the revolt at Attica, by the death of George Jackson, by the war in Vietnam, by the general rise of protest in the country. In this process, men, who had not gone in as “political” prisoners, who had been what we call common criminals, began emerging rehabilitated. But not in the way the government talks of rehabilitation, not obsequiously taking their place in the accepted, legal criminal order of things. Rather as rebels and organizers, as thoughtful, militant men ready to devote their lives to abolishing prisons along with that complexity of conditions that makes prisons seem logical.

© Howard Zinn, 1974. Reprinted with permission of Haymarket Books from Justice in Everyday Life.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn