By Bill Bigelow, Jesse Hagopian, Cierra Kaler-Jones, Ana Rosado, and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

This lesson is part of a suite of activities developed to accompany How the Word Is Passed by a Zinn Education Project curriculum collective, which includes the authors listed above.

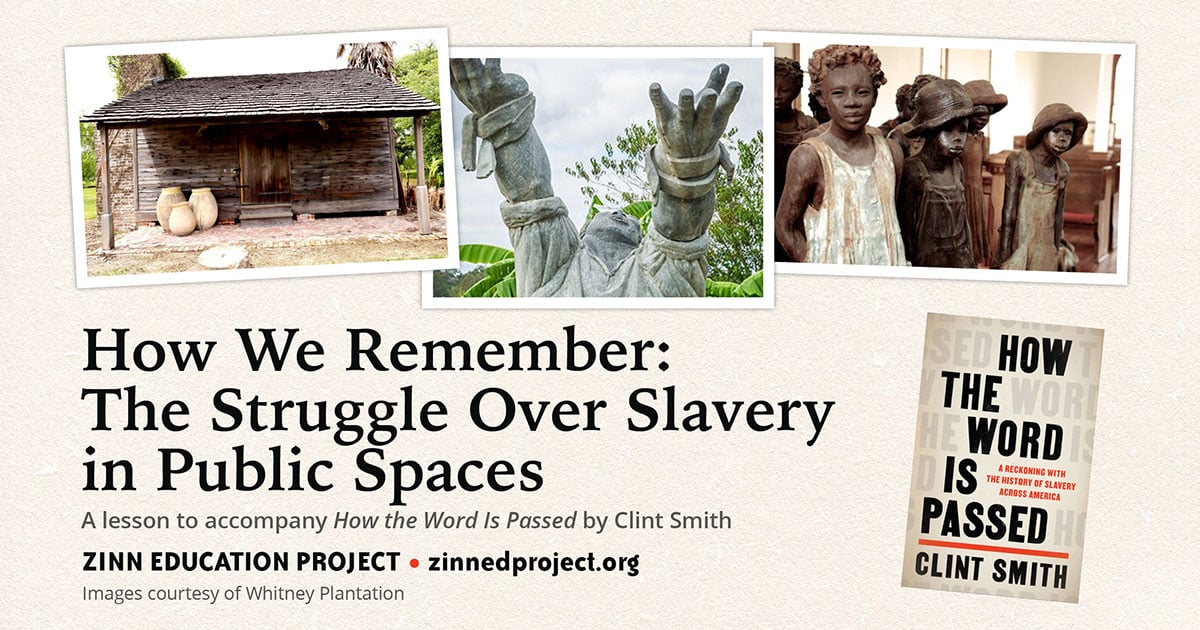

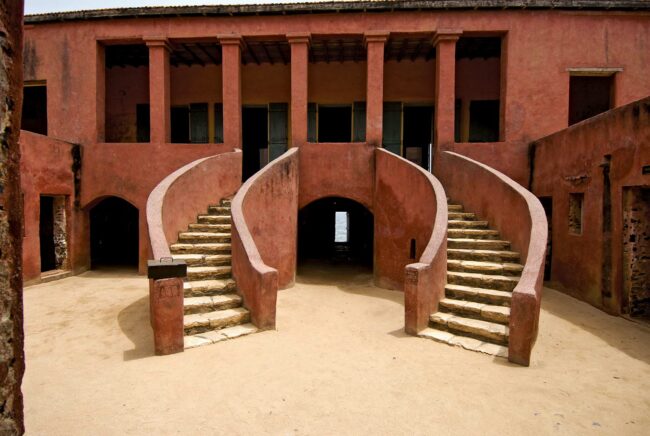

In the prologue to his book How the Word Is Passed, Clint Smith writes that “The echo of enslavement is everywhere.” How the Word Is Passed captures a few of these echoes and tries to make sense of them for our lives today. Smith shows how in different sites, slavery is remembered, slavery is distorted, and slavery is forgotten. He travels to Thomas Jefferson’s home of Monticello, where, during Jefferson’s life at any given time, he enslaved 130 people; to the Whitney Plantation outside of New Orleans, near the largest revolt of enslaved people prior to the Civil War; to Louisiana’s Angola State Prison, site of a former plantation; to the Confederate burial ground of Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia; to Galveston Island, home of the first Juneteenth commemoration, where the first non-Native enslaved person arrived in 1528; to New York City, which on the eve of the American Revolution had the highest proportion of enslaved Black people to Europeans in the North; to Goree Island in Senegal, a center of the trade in enslaved Africans from the 16th century to 1848.

In the prologue to his book How the Word Is Passed, Clint Smith writes that “The echo of enslavement is everywhere.” How the Word Is Passed captures a few of these echoes and tries to make sense of them for our lives today. Smith shows how in different sites, slavery is remembered, slavery is distorted, and slavery is forgotten. He travels to Thomas Jefferson’s home of Monticello, where, during Jefferson’s life at any given time, he enslaved 130 people; to the Whitney Plantation outside of New Orleans, near the largest revolt of enslaved people prior to the Civil War; to Louisiana’s Angola State Prison, site of a former plantation; to the Confederate burial ground of Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia; to Galveston Island, home of the first Juneteenth commemoration, where the first non-Native enslaved person arrived in 1528; to New York City, which on the eve of the American Revolution had the highest proportion of enslaved Black people to Europeans in the North; to Goree Island in Senegal, a center of the trade in enslaved Africans from the 16th century to 1848.

Finally, Smith returns to his own family, whose ancestors were enslaved, to make sense of the intimate, close-to-home impact of the “crime that is still unfolding.”

In his research for How the Word Is Passed, Clint Smith spoke with people who “are, formally or informally, public historians who carry with them a piece of this country’s collective memory.” This activity asks students to imagine them selves as “public historians,” trying to draw on an infinitely painful history to help us make sense of our society today.

How should we “teach” about the meaning of each of these places in a way that educates people about the truth of U.S. history? And about what that history demands of us now? Those are the questions students confront here.

In the lesson, students receive facts about each of the locations in How the Word Is Passed and imagine how they might commemorate what occurred there. If time allows, students can supplement these fact sheets with their own research. Each instruction sheet for students encourages them to think beyond traditional museum remembrances — although museums themselves needn’t be the staid, neutrality-feigning sites of yesteryear. As Smith points out in the book’s Epilogue, the National Museum of African American History and Culture “recognizes that Blackness is not peripheral to the American project; it is the foundation upon which the country is built.” That is the sensibility we hope students will bring to each of their commemoration proposals.

Classroom Stories

I currently teach U.S. History I and II to 10th and 11th graders, respectively. We wrapped up our semester this week by holding midterm exams. In lieu of a traditional exam for one of my U.S. History I classes, I had them complete the Zinn Education Project activity “How We Remember.” I had read Clint Smith’s book last year and was blown away by how the history is handled at many of the highlighted locations and his extreme attention to detail.

I’ve since used excerpts from Smith’s book in class, but this activity really had the students use the text in a way that required them to interact with the sites, as well. The commemorations were thoughtful and the students did an incredible job bringing justice to the history of enslavement at those locations. Here are some examples:

The students who were assigned New York City created three works of art to display in Central Park as a way to commemorate work of Black abolitionists and Seneca Village. One work of art was a 3-D rendering of a bed with turned down bedding and a doll on the floor. It was meant to signify the upending and displacement of the Seneca Village community.

The students who were assigned Angola created a script for a guided tour. They included images and provided visuals to go along with the script. The brutal facts of Angola as a plantation and as a prison were presented. In the end, “visitors” were encouraged to sign a petition to close Angola. The plan was to make it a museum that focuses on the history of Black Americans’ struggles both during and after enslavement.

The students who were assigned Monticello created a sculpture which highlighted a number of the enslaved at the plantation. The sculpture included silhouettes of mothers and fathers and beads to represent their children. The purpose was to highlight family separation. On the top of the sculpture was a representation of Monticello; placing it on top of the enslaved was meant to demonstrate the fact that Monticello and Jefferson’s success came at the expense of the enslaved.

Thank you for such an engaging and important activity. I look forward to using it again in the future.

With teaching U.S. history in a different country, we are always striving to find connections and impacts that apply to our local contexts. With Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed, our class found a wonderful way to connect contested histories both in the United States and Canada.

In using the How We Remember lesson plan, our students engaged with Smith’s writing and started to explore the spaces he visited where the history of enslavement is either remembered or forgotten.

The Métis Walking Tour

Our students became ‘curators of difficult knowledge.’ They were tasked with coming up with a way to both uncover the hidden histories of a particular place, while also creating a site of remembering that honours true history, and invites learning and community.

As a wrap up to their projects, the students connected their learning by travelling to The Forks in Winnipeg, Manitoba (a contested historical site) to see how the past is remembered in a Canadian context. Leading our workshop was an Indigenous Education Leader from Louis Riel School Division. He compassionately led our team through the Métis Walking Tour. We learned about the rich Indigenous histories as well as the history of colonization in the area. The message was clear, first we must learn what has been deliberately forgotten, then we must find a way to move forward, collectively for a better future. Thank you to Louis Riel School Division!

The Forks in Winnipeg, Manitoba

As a rural K–12 school, we rarely get opportunities to connect with students and teachers from urban schools in our province. In order to bridge that divide, we collaborated on this project with Mr. Jared Suderman from Glenlawn Collegiate in Winnipeg. Our students met up prior to the tour and were able to share a meal together and create community prior to engaging with the tour.

In my opinion, this was a rich learning experience that taught the whole team about the complexities of presenting history in public spaces!

As a school, every high schooler taking U.S. history went on a field trip to Gettysburg this spring. Students had read several chapters from Zinn’s A People’s History dealing with the Civil War and Reconstruction. While at Gettysburg, we saw several tour vans celebrating both the U.S. flag and Dixie.

Upon our return to campus and reflection, we used the How We Remember lesson and discussed specifically Thomas Jefferson, how he is remembered and what is being glossed over. Seeing the large number of artifacts celebrating war at Gettysburg — so many displays of guns, weapons, and tactics — really brought home how focused U.S. history tends to be on “war guys” and the weight placed on this narrative as opposed to the realities of why young men were dying, and why human beings had been enslaved.

While certainly not a pleasant discussion, seeing how focused this National Park was on celebrating war was sobering in contrast to the plight of enslaved people. While approximately 700,000 died during the Civil War, estimates are that over 4,000,000 people were enslaved.

I used the Zinn Education Projects lesson How We Remember: The Struggle Over Slavery in Public Spaces, which utilizes Clint Smith’s book as a point of reference. This lesson helped prepare my students for their upcoming state assessment that seeks answers to the question “To what extent should leaders be commemorated?”

I combined the resources from this lesson with past events students could recall such as the tearing down of confederate statues of Robert E. Lee — particularly in Richmond, since we are in close proximity to that area — as well as the move to change the name of Jefferson Davis Highway to Emancipation Highway, since our school sits on the intersection of that highway. The lesson was a perfect way to tie together current events and the past to help students better grasp modern social movements — like how we commemorate leaders and how we remember slavery in public spaces.

The lesson features facts about Monticello and Jefferson’s relationship with those he enslaved, which aligned seamlessly with our state standards. The opportunity for students to examine the past, and move forward with commemorations for how the enslaved should be remembered, was the perfect social justice learning experience. I look forward to using this lesson in my future Black history and U.S. history courses!

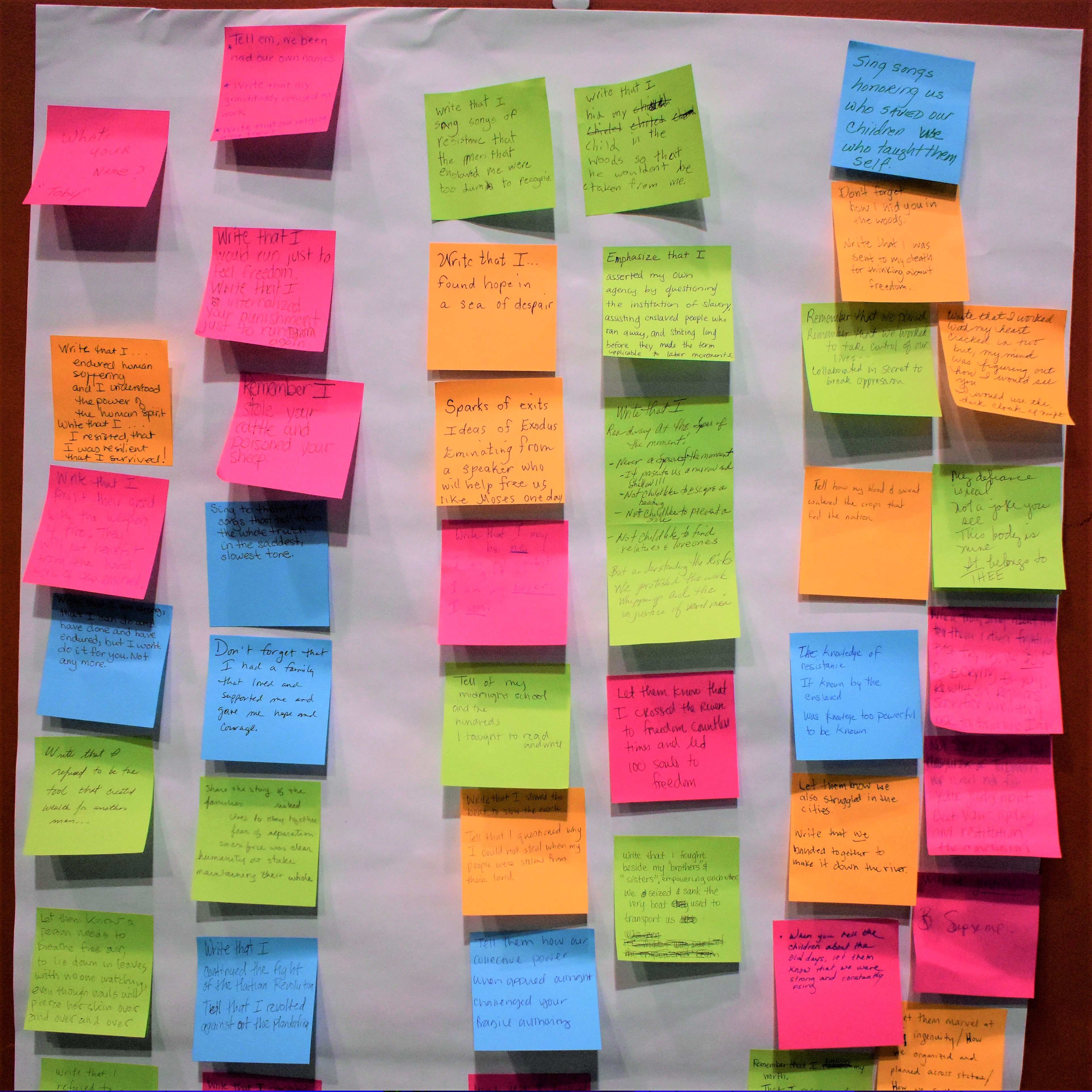

Below is an example of a student presentation following the lesson.

I have an AP Language class that is focusing on point of view and rhetoric. I give them prompts daily and ask them to explain what the author is saying, who is audience is and why they chose the words/phrases and examples they used, how it impacts and convinces the audience etc. I have been using quotes from Clint Smith’s “How the Word is Passed” not only is it fascinating it really resonates with my students and makes them think beyond and really delve into his words. I plan to do this with the other suggested books, this is just the beginning!