One of the teachers who piloted the Make Reconstruction History Visible project with her students wrote a description of the process she used. She is a middle school teacher and had two days. A number of her students’ entries were selected for the D.C. section of the Reconstruction history map.

By Amy Trenkle

I had only two more days in my unit. The school year was coming to an end. My students’ course of study, chronologically, was the First Americans through Reconstruction. It’s a full academic year. In this last unit, we looked at innovation, integration, and revolution from the Antebellum period, Civil War, and Reconstruction. Now, at the end of the year, I had four school days to teach Reconstruction. Not enough.

Prior to this lesson we read a letter from a free man, Jourdan Anderson, to his former “master,” Colonel Anderson, to set the tone and open the discussion on the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. The following day, we examined primary source documents to discuss the successes and failures of Reconstruction and why Reconstruction did not succeed.

Thanks to Teaching for Change for introducing me to the Zinn Education Project’s “Make Reconstruction History Visible” project, I decided to use our final two days to have students look at places in Washington, D.C., that are tied to Reconstruction. Some are sites my students pass every day. Others are sites they had not heard of.

As part of a larger course of study, our students spent the year visiting sites throughout Washington, D.C., to see who was and was not commemorated, explore these people/places, and make connections to our classroom studies. This activity on Reconstruction was a wonderful way to tie both our discussion on Reconstruction and our city sites project together.

I first introduced the idea of a historic marker to the students by finding a marker on the Colfax Riot in Louisiana. The marker is sparse. It reads, “On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873 marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

I asked the students to read the text and write one fact they learned and something they wondered. After debriefing with them and hearing their thoughts, I provided further information to help them better understand the context, and provide more depth and history. I asked them why historic markers are important and whether they thought this particular marker was appropriate for the history it was trying to convey. All agreed this marker did not share enough information. While no one challenged the term “Carpetbag misrule” they did point out that they felt that the marker was biased in its telling of the history.

This was a great jumping off point for my students. I told students that our aim for the day was to learn of historic sites in D.C. that are related to the Reconstruction Era and to write a label text for the site.

Students were already seated at tables of three or four. I gave each group a folder. Inside the folder, I included a page of historic sites in D.C. that related to Reconstruction and a brief summary of them.

In pairs, or by themselves, I asked students to choose one site that interested them and that no one else chose at the table.

Once students identified who they were working with (if anyone) and confirmed their site, they retrieved a laptop from the cart and began to research their site.

On the screen, I provided them directions for how to share their research:

Create three slides:

Slide 1:

Name of Historic Site in D.C., Student Name(s), Location of site in D.C. (physical address, ward, neighborhood), photo of site

Slide 2:

If you were to write a historical plaque for this site, what would it say? The description must be historically accurate and written in your own words. Do not copy from the internet.) Why is the site historically important? How is it connected to Reconstruction? (Approx.100-150 words — this slide is approx. 100.)

Slide 3:

Cut and paste the link of the website (URLs) where you found the information you will use: (Do not use Wikipedia.) 1-2 sources minimum

Share your slides with my Gmail address so that they are all on my drive for our presentations.

Students were on task for the remainder of the period. The three slides seemed manageable and fun for them to create. It was not much different from what I’d asked them to do previously in the year and by working together; students helped each other to find accurate information, write with a purpose, and complete the assignment.

I told students they could work on it that night if they needed to but they did not have to.

The next day, the students came back ready to present. For the warm-up, I had two questions:

- How does Reconstruction help us understand events in today’s society? Give an example.

- If we were to create a list of sites, similar to what we did yesterday, but for today in D.C., can you think of any places where you would want a historical marker? What for? Is there somewhere not in D.C. that you think is important? Explain.

I knew they could make connections to the first question. For the second question, I wanted to see what they had to say.

I’m not sure I would use the second question again, because I needed the additional time for presentations and the question seemed to confuse most of the students. The first question, however, was helpful and helped them to make connections between what they were learning and our lives today.

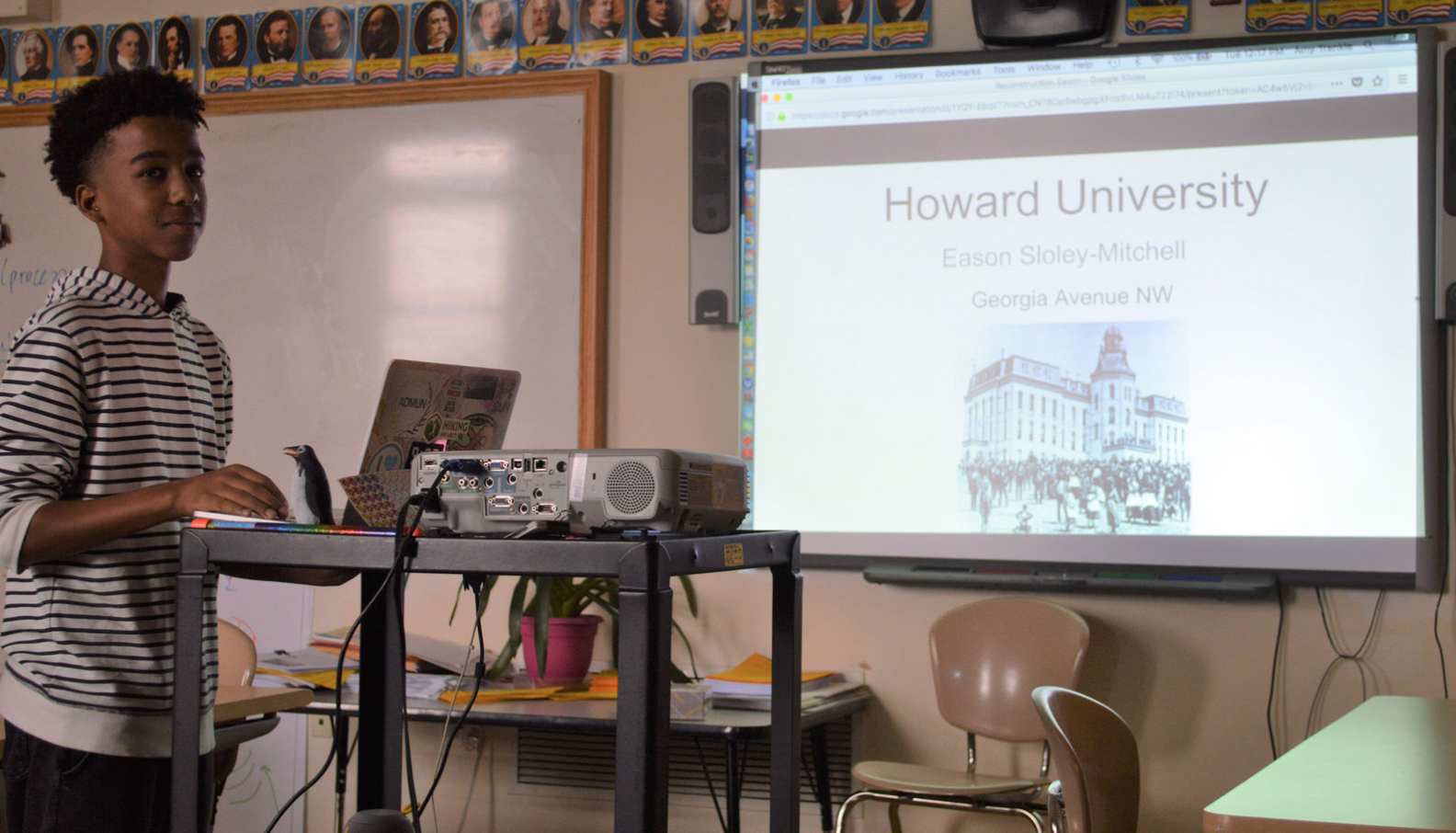

I asked for students to volunteer to present. There was good participation. Most students were eager to share what they had learned.

When making the assignment, I originally wanted to have a big map of D.C. so that students could place their site on the map. Because I was rushed for time, I eliminated that when creating my lesson. In the future, I will put that step back in. It’s important for students to see on a map where these sites are and where they are in relation to each other. Nqobile Mthethwa, of the Zinn Education Project, had a great idea of being able to look at the sites and neighborhoods and draw conclusions to our lives in D.C. today (perhaps gentrification, etc.).

As the students presented, I had them complete a simple chart. The chart asked them to write down the site name (which was on the slide before them) and then the connection to Reconstruction. Most students were able to present. But I had a few in classes that were more than 25 that were unable to present due to time restrictions. I tried to end class with two minutes left to have students complete an exit ticket. My exit ticket asked:

In one or two sentences, on the back of your notes, please share what you learned about Reconstruction from our presentations today.

In one sentence, share the impact of Reconstruction on Washington, D.C.

“I learned that a lot of the places in D.C. helped the Black community become united and stronger. The sites helped them thrive during the Reconstruction era. Reconstruction made D.C. a more diverse community and made it how it is today.” — Ellen

“I learned that many churches and schools were built for African Americans during Reconstruction, but they usually had minimal and insufficient resources. Reconstruction led to more establishments in D.C. for African Americans.” — Evelyn

“I learned that African Americans were offered new opportunities, like a good education and the right to run for office. Reconstruction both divided D.C. like in Lincoln’s assassination but also there were many great opportunities in D.C. like new Black schools.” — Meyer

All in all, this was an excellent assignment. The students really enjoyed it. In their end of the year survey, many asked to study Reconstruction longer and quickly understood its impact on where we are today. One student wrote,

I think that we could’ve spent more time on Reconstruction. . . . I feel like Reconstruction helps develop what we think of the country more than the Civil War does.

Thank you to the Zinn Education Project for helping me rethink how I teach Reconstruction and creating an opportunity for my students to learn more about history through their city!

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn