Was it the “Philippine-American War” or the “War of Philippine Independence”? Was Emilio Aguinaldo a “rebel leader” or the “President” who led the Filipinos in the war against the United States?

Was it the “Philippine-American War” or the “War of Philippine Independence”? Was Emilio Aguinaldo a “rebel leader” or the “President” who led the Filipinos in the war against the United States?

For the past 12 years, I have tried to help my 11th-grade students view U.S. history critically from multiple perspectives.

While I use primary sources and other historians’ interpretations, I continually search for sources that go beyond the mostly benign representations of U.S. actions overseas, which have dominated textbooks for generations. This is not just academic; how students regard U.S. conduct in the past influences how they view the exercise of U.S. power today.

Therefore, when I read Dana Lindaman and Kyle Ward’s book, History Lessons: How Textbooks from Around the World Portray U.S. History, I was excited to find textbook passages from countries that could help my students recognize that their texts are not impartial.

Recently, I asked students to compare an account from their U.S. history textbook on the Philippine-American War with a Filipino textbook passage from History Lessons about the same event — called the War of Philippine Independence in the Filipino book.

In order to help students unravel the perspectives presented in both nations’ textbook accounts, I first taught lessons that offered students a range of viewpoints on this event. First, students watched the video, Savage Acts. This documentary depicts U.S. racism to help explain the expansionist policies to “civilize” the Philippines at the turn of the century. For instance, the video describes how 1,200 Filipinos were brought to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and placed on exhibit. One American observer said that she saw “the wild barbaric Igorots who eat dogs and are so vicious that they are fenced in. They thirst for blood and are the lowest type of civilization I saw.” With the prevalence of these racist attitudes, it is not surprising to hear U.S. Col. Frederick Funston say that the Filipinos “are as a rule an illiterate, semi-savage people who are waging war not against tyranny but against Anglo-Saxon order and decency.”

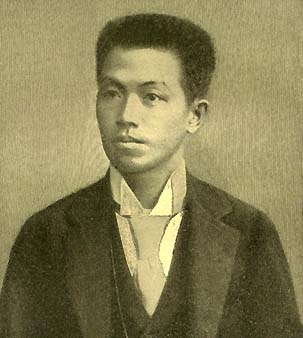

Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo (ca. 1898)

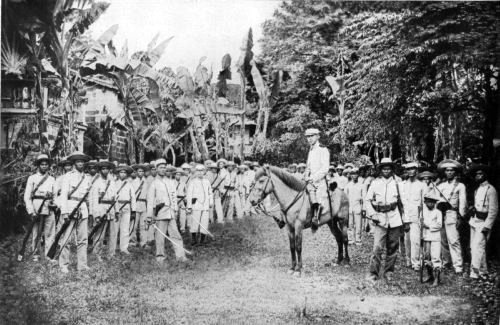

Savage Acts points out that after Filipinos expelled the Spanish, they established their own independent government. But instead of recognizing Filipino independence, the United States annexed the Philippines and sent troops to crush any resistance. The video examines these events from multiple points of view ranging from antiwar activists like Mark Twain to supporters of imperialism like President William McKinley and describes the camps where U.S. soldiers tortured Filipinos.

After the video, I gave students eight primary source documents representing an array of perspectives on U.S. annexation. These included speech and article excerpts from McKinley, William Jennings Bryan, Sen. Alfred Beveridge, labor leader Samuel Gompers, the “Colored Citizens of Boston,” Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo, a Filipina activist named Clemencia Lopez, and a Filipino newspaper.

I divided the class into eight groups and assigned each group one of the packet’s eight documents. Students wrote summaries and their own assessment of the strengths and limits of the document’s perspective. Then, one student from each group represented the perspective from his or her group’s assigned document in a panel discussion. (I borrowed this lesson idea from the website of the American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning, the organization that created the Savage Acts video. Visit the American Social History Project for all the documents.)

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn