By the editors of Rethinking Schools

As Mark Hertsgaard and Kyle Pope wrote recently in The Nation, “There is a runaway train racing toward us, and its name is climate change. This is not alarmism: It is scientific fact.”

This is where the Green New Deal, introduced in February by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Edward Markey, begins: with the terrifying prospects of the runaway train of climate catastrophe. But the Green New Deal seeks to mobilize people not from fear, but from hope — hope for a radical transformation of society. It’s a manifesto that begins with the imperative of dramatically cutting greenhouse gases — global reductions of 40 to 60 percent in emissions from 2010 levels by 2040, reaching net-zero global emissions by 2050.

Why the Green New Deal? Ocasio-Cortez, supporters in the Sunrise Movement, and others, draw inspiration from the audacious initiatives of the Depression-era New Deal programs, as well as the massive World War II mobilization. Because anything less is inadequate to the urgency of the crisis, as laid out starkly in last October’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. But the new New Deal explicitly rejects the racism of its antecedents, which, for example, excluded agricultural and domestic workers from Wagner Act union protections and baked in a future of racially segregated housing through Federal Housing Administration policies.

The Green New Deal imagines a vast social reconstruction that will meet 100 percent of U.S. demand for power through clean, renewable, and zero-emission energy sources; upgrade buildings in the United States to achieve greater energy efficiency, water efficiency, safety, affordability, comfort, and durability; support sustainable family farming and build a sustainable food system; create millions of good, high-wage jobs; provide “unprecedented levels of prosperity and economic security for all people of the United States”; and more.

The Green New Deal is not just about suppressing carbon emissions, it’s also about democratizing decision-making. It calls for the use of “democratic and participatory processes that are inclusive of and led by frontline and vulnerable communities and workers to plan, implement, and administer the Green New Deal mobilization at the local level.” It concludes by promising “high-quality health care,” “affordable, safe, and adequate housing,” “economic security,” “clean water, clean air, healthy and affordable food, and access to nature.”

It imagines a very different country from the one we now live in.

And schools? The Green New Deal includes only one line about “providing resources, training, and high-quality education,” and, in fact, never mentions the word schools. Nonetheless, the Green New Deal has profound implications for schools, and offers an extraordinary opportunity for social justice educators to draw on the utopian — in the best sense of the word — vision laid out in the congressional resolution.

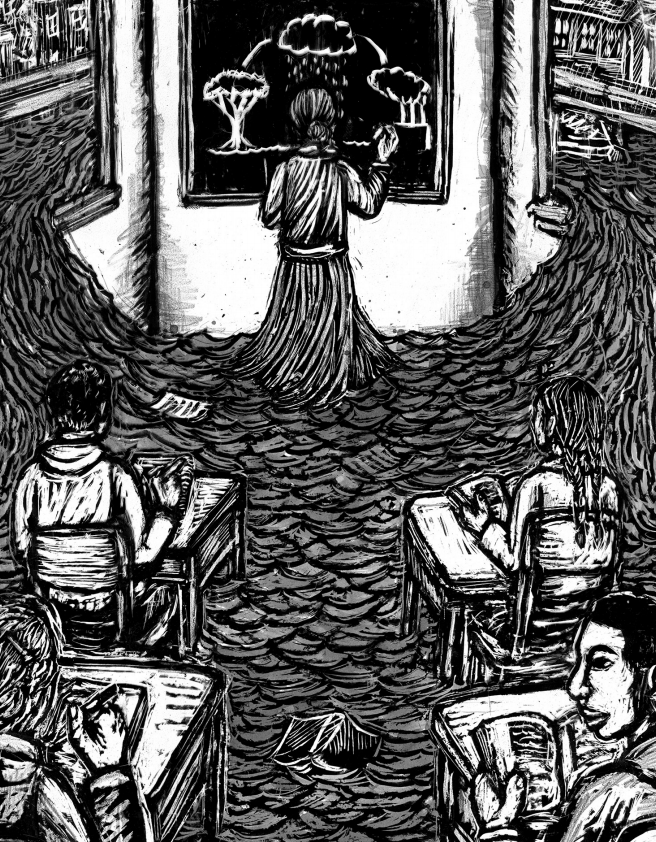

Let’s start in our classrooms. The revolutionary aspirations of the Green New Deal will only be brought to life by people who grasp the enormity of the crisis that humanity faces and the radical changes necessary to address it. This requires that we teach a climate justice curriculum that:

• engages students in the science of climate change;

• probes the social and economic roots of climate change;

• emphasizes the brutal inequality that results in those least responsible for the crisis being hit the hardest;

• alerts students to the breadth of global activism for climate justice;

• helps students see how climate justice is inextricably linked to addressing broader issues of racism, militarism, imperialism, and class exploitation;

• invites students to imagine a society based on principles of ecology and social equality; and

• encourages students to come to see themselves as activists for a green and just world.

A climate justice curriculum would nurture more students like Isha Clarke. Clarke is an 11th grader at MetWest High School in Oakland, California. She was one of the young people who confronted Sen. Dianne Feinstein, hoping to convince her to endorse the Green New Deal. The video of students’ frustrating meeting with Feinstein went viral. In an interview in Grist, Clarke was asked why she wants to focus on the Green New Deal, with so many other important issues to fight for. Clarke responded:

I am a young woman of color, so I feel drawn to a lot of issues. Part of the reason why I’m working on the Green New Deal right now is because I think it is the most intersectional plan that I’ve seen ever, and it really excites me that I can work for everything I believe in in this one deal. It encompasses economic justice, climate justice, racial justice, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, all of that can be part of the Green New Deal. You can’t separate climate justice from any other justices because they’re all-in-one. So when I’m fighting for climate justice, I’m fighting for everything else, too.

This is the kind of excitement and insight that a climate justice curriculum can generate.

The curricular rethinking required by the Green New Deal needs to go on at all grade levels and in all disciplines. Rethinking Schools has featured stories about what this work looks like in early childhood education [“A Pedagogy for Ecology”], 3rd grade [“The (Young) People’s Climate Conference”], middle school language arts [“Teaching to the Heart”], high school social studies [“Standing with Standing Rock”], high school chemistry [“Students ‘Warrior Up’ for Climate Justice”], and in this summer 2019 issue of Rethinking Schools, middle school math [“Solar Power Comes to Math Class”]. Most of these, and many more, have been collected at our Zinn Education Project’s “Teach Climate Justice” campaign page.

As our Green New Deal society moves decisively away from fossil fuels, and toward a carbon-free future, and as infrastructure is reconstructed, our students will need to develop the technical skills, as well as the activist sensibilities, that can “bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old.” This is career education, but not the conservative version where students were taught to seek out jobs in a fundamentally exploitative, unsustainable economy. A Green New Deal needs a new generation of architects, engineers, city planners, builders, farmers, technicians, scientists, and yes, teachers. Our classrooms and curricula should invite the radical imagination of our students — and encourage them to think of themselves as contributing to the just transition to a new economy.

As our Green New Deal society moves decisively away from fossil fuels, and toward a carbon-free future, and as infrastructure is reconstructed, our students will need to develop the technical skills, as well as the activist sensibilities, that can “bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old.” This is career education, but not the conservative version where students were taught to seek out jobs in a fundamentally exploitative, unsustainable economy. A Green New Deal needs a new generation of architects, engineers, city planners, builders, farmers, technicians, scientists, and yes, teachers. Our classrooms and curricula should invite the radical imagination of our students — and encourage them to think of themselves as contributing to the just transition to a new economy.

Some of this work can begin by educators helping students to think critically about their own school grounds and school buildings. For example, many schoolyards have extensive and needless amounts of paved or impervious surfaces. Most students still attend schools powered by fossil fuels. They often travel to and from school in vehicles powered by fossil fuels. It’s likely that the school cafeteria does not feature a menu shaped by principles of climate and food justice. All this needs to change. In partnership with educators, parents, artists, environmental activists, and community organizations, our students can help rethink and green our schools.

Too often, we think about the curriculum only as what transpires in our classrooms. But curriculum is everything that students experience, everything they learn, at school. Thus, the school site itself is curriculum. The aspirations of the Green New Deal need to find expression in the places that our students — and educators — spend so much time. We need to green our schools for the survival of the planet, as well as for students’ health — and we need to green our schools to alert our students to the character of the society we are hoping to build.

Individual teachers can help launch these changes. But our unions have an important role to play. First, our unions need to educate members about the Green New Deal and initiate conversations about what it could mean in their school district and how it can be supported politically. Teacher unions can promote “Teach Climate Justice” curriculum work and encourage teachers to weave climate issues into their classrooms. They can insist that politicians seeking union endorsement announce their support for the Green New Deal, for climate justice education, and refuse to accept fossil fuel contributions. Unions can join with other unions to articulate and work for a Green New Deal social vision — one that also includes schools.

The Green New Deal can also provide a framework for our unions to “bargain for the common good.” Teacher unions should fight just as zealously for our planet as for our pay, our health care, and our retirement. Indeed, climate science says that all these are inseparable. “What good is it to negotiate the assignment of overtime when the sky is on fire?” asks Nato Green in his valuable In These Times article, “Why Unions Must Bargain Over Climate Change.”

The Green New Deal can also provide a framework for our unions to “bargain for the common good.” Teacher unions should fight just as zealously for our planet as for our pay, our health care, and our retirement. Indeed, climate science says that all these are inseparable. “What good is it to negotiate the assignment of overtime when the sky is on fire?” asks Nato Green in his valuable In These Times article, “Why Unions Must Bargain Over Climate Change.”

Green offers suggestions for how public sector unions can bargain in ways that support the Green New Deal. Some of these can be adapted to teacher unions. In bargaining, our unions could include demands for school buildings to be converted to 100 percent renewable energy; school buses to abandon the use of fossil fuels; school buildings to be retrofitted for energy efficiency; more trees to be planted on school grounds and schools made more bike-friendly; reduction in carbon emissions with greener food procurement policies; and subsidized student transportation on public transit. Sure, these are “permissive” bargaining items, which districts are not required to address. So what? This is a climate emergency; the moment demands audacity. Green’s own union, SEIU Local 1021 in San Francisco, joined the campaign to divest their pension fund of fossil fuel stocks and to stop a new coal terminal in the Port of Oakland.

And teacher education programs need to ask themselves whether they are graduating new teachers who embrace how central this just transition work is to their students’ lives, as well as their own. Teacher ed programs should make sure that climate justice curriculum is incorporated into methods classes for all grade levels and all disciplines and that future teachers come to recognize that it is their moral and civic responsibility to see climate justice education as an essential part of K–12 education.

At this stage, the Green New Deal is not legislation, it’s inspiration. But the social vision expressed in House Resolution 109 will require massive public investment, and we need to be doing everything we can to build support for it now. No doubt, in 2019, with Republicans controlling the Senate, and a pro-corporate, climate-denying zealot in the White House, the Green New Deal finding its way into legislation is unlikely. Our job is to nurture the aspiration for the just transition away from fossil fuels and, as educators, to flesh out what this will look like in schools. The principles of the Green New Deal should be fundamental to our vision of what a more just public education system looks like.

So often, the climate crisis is presented in frightening, threatening terms: rising seas, superstorms, raging wildfires, unlivable temperatures, species extinction, disappearing glaciers, dying coral, climate refugees. These are real. But the paradox is that this dystopian possibility is forcing us to imagine an entirely different kind of society. Schools have a central role to play in devising new alternatives and equipping young people to bring those alternatives to life. This is the work we’ve been assigned.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of Rethinking Schools. Subscribe to Rethinking Schools magazine today.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of Rethinking Schools. Subscribe to Rethinking Schools magazine today.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn