Tessie McGee read to her class in a steady measured tone, quietly engaging in a calculated act of subversion. She was Black, 28-years-old, and taught history in 1933-1934 at the only Black secondary school in Webster Parish, Louisiana.

On many occasions, McGee made what she deemed to be necessary revisions to the mandatory curriculum. Based on her own judgment, and perhaps at the recommendation of fellow Black teachers, she often read passages from Carter G. Woodson’s “book on the Negro,” which rested comfortably in her lap. She kept the book out of sight, understanding the likely repercussions were she to be caught. Like most Black educators, Miss McGee was a public employee and vulnerable to the disciplinary practices of Jim Crow authorities.

But she was undeterred. “She read to us from that book,” one of McGee’s students recounted. “When the principal would come in, she would . . . simply lift her eyes to the outline that resided on the desk and teach us from the outline. When the principal disappeared, her eyes went back to the book in her lap. . .”

“Black Education was a fugitive project from its inception — outlawed and defined as a criminal act regarding the slave population in the southern states and, at times, too, an object of suspicion and violent resistance in the North.” So begins Jarvis Givens’ masterful work, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching.

“Black Education was a fugitive project from its inception — outlawed and defined as a criminal act regarding the slave population in the southern states and, at times, too, an object of suspicion and violent resistance in the North.” So begins Jarvis Givens’ masterful work, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching.

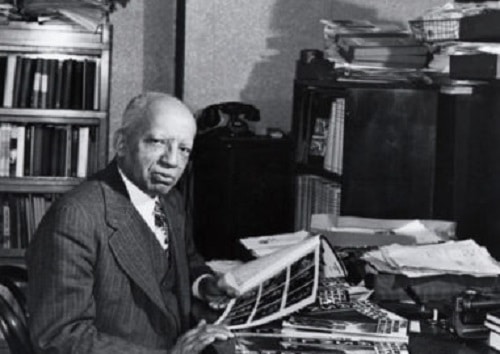

Givens’ work details the long assault on Black education that occurred from the period of enslavement through the life of one of the founders of the Black studies tradition, Carter G. Woodson. Givens notes,

Anti-literacy laws targeting Black people were older than the United States itself. The first law of this kind was a slave code enacted in 1740, in reaction to the Stono Slave Rebellion of 1739 in South Carolina.

Givens aptly describes the “intellectual surveillance” of Black people that has always been part of U.S. education and the paranoia that white supremacists have had about Black education. He underscores this point by quoting abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ enslaver who said that a slave who learned to read and write against the will of his master was tantamount to “running away with himself.”

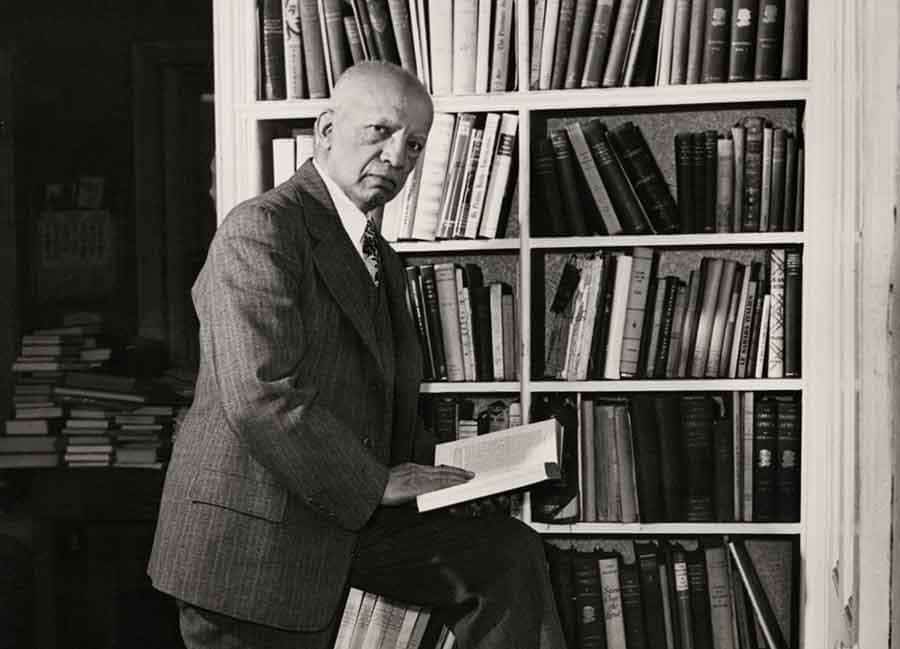

Central to Givens’ telling of the role of education in the Black freedom struggle is his portrait of Woodson who wrote numerous textbooks to counter white supremacist lies about Black history; founded Negro history week, which later became Black History Month; and wrote one of the seminal text in the Black studies tradition, The Mis-Education of the Negro.

The current assault on critical race theory and antiracist pedagogy by the right-wing is unintelligible without the insights offered in Fugitive Pedagogy and Givens’ inspirational stories of Black educators who faced down intellectual abuse and physical violence to create counter-narrative curriculums that were “a literary genre inaugurated by runaway slaves . . . Black curricular imaginations of the post-Emancipation era . . . informed by a fugitive literary culture with antebellum roots.”

9780674983687 | Harvard University Press

Listen to the audiogram below of Jarvis Givens from his Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class, Fugitive Pedagogy Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching, and find a video recording and resources from that class here.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn