In the 1960s, Howard Zinn, along with Ella Baker, served as advisers to SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

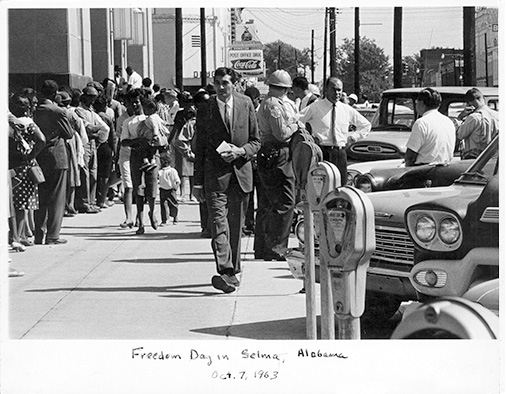

For teaching about the Civil Rights Movement in Selma, here is Zinn’s first-hand account from Selma’s Freedom Day on October 7, 1963. “The idea was to bring hundreds of people to register to vote, hoping that their numbers would decrease fear. And there was much to fear,” Zinn writes.

The following excerpt is from Chapter 5 of Zinn’s autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train and is followed by related resources about Selma’s voting rights campaign, Freedom Day, and SNCC.

By Howard Zinn

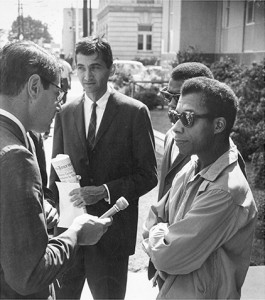

Howard Zinn, James Baldwin, and a journalist on Freedom Day in Selma, Alabama, October 7, 1963.

I traveled to Selma, Alabama, in October 1963 as an adviser to SNCC, to observe its voter registration campaign there, which had been accompanied by a number of acts of intimidation and violence. The town was the seat of Dallas County, whose population was 57-percent Black, with 1 percent of those registered to vote. (Sixty-four percent of whites were registered.)

My experience in Albany had made me especially conscious of the federal role in keeping the institutions of racism going. A systematic failure to enforce civil rights law had marked every national administration since 1877, whether Democrat or Republican, liberal or conservative. Racism was not southern policy, it was national policy. Selma was an American city.

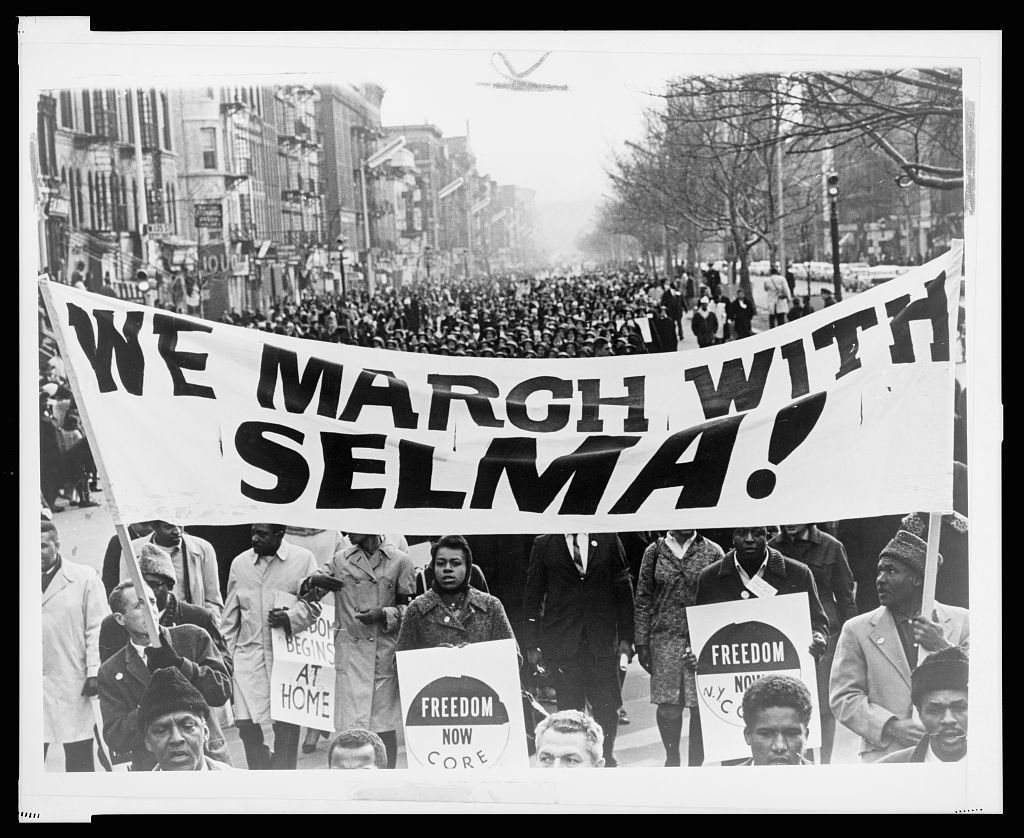

SNCC had declared October 7 as Freedom Day. The idea was to bring hundreds of people to register to vote, hoping that their numbers would decrease fear. And there was much to fear. John Lewis and seven others were still in jail. Sheriff Jim Clark, huge and bullying, had deputized a force that was armed and on the prowl. To build up courage, people gathered in churches night after night before Freedom Day. The churches were packed as people listened to speeches, prayed, sang.

Two nights before Freedom Day, I went to a crowded church meeting to hear [comedian and activist] Dick Gregory, who had just arrived in Selma; his wife Lillian had been arrested while demonstrating there. Armed deputies ringed the church outside. Three white police officers sat in the audience taking notes, and Gregory was determined to speak about them and to them in a manner unheard of in Selma — to show that it was possible to speak to white people insubordinately.

He spoke for two hours, lashing out at white Southern society with passion and with his extraordinary wit. Never in the history of this area had a Black man stood like this on a public platform ridiculing and denouncing white officials to their faces. The crowd loved it and applauded wildly again and again. He spoke of the irony of whites’ maltreatment of Black people, whose labor they depended on for their lives. He said he wished that the whole Negro race would disappear overnight — “They would go crazy looking for us!” The crowd roared and applauded.

Then Gregory lowered his voice, suddenly serious. “But it looks like we got to do it the hard way, and stay down here, and educate them.”

After him, Jim Forman spoke. He was the executive director of SNCC, working in the Atlanta office, but moving onto the firing line again and again with an awesome quiet bravery. He was Chicago born, but grew up in Mississippi, spent four years in the Air Force, was a college graduate. Now he set about organizing the people in the church for Freedom Day. “All right, let’s go through the phone book. . . .You take a baloney sandwich and a glass of cool water and go down there and stay all day.” He pointed to the big sign up on the platform: DO YOU WANT TO BE FREE? He paused. “Who’ll take the letter A?”

The evening ended with the Selma Freedom Chorus, including some small children, some teenagers, and a boy at the piano — the most beautiful singing I had heard since the mass meetings in Albany. (That is something impossible to convey in words — the singing, the ever-present singing — in churches, at staff meetings, everywhere, raising the emotional level, giving people courage, almost always ending with everyone, knowing one another or not, holding hands.)

By 11 a.m. there were two hundred and fifty people in the line, which extended the full length of the block, around the corner, and halfway down that street. Standing guard over these people — including elderly men and women, young mothers carrying babies in their arms — were helmeted men with clubs and guns, members of Sheriff Jim Clark’s posse. The sheriff was there, a six-footer with a big belly, on his green helmet the confederate flag and a gold medallion with an eagle, a gold star on his shirt, epaulets on his shoulders, gun at his hip.

On Freedom Day, Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark and his armed deputies were closely watching the large gathering crowd, and as the line grew, so did Sheriff Clark’s irritation. Those attempting to bring food and water to those in line were beaten and arrested, even though Justice Department lawyers were watching from the Federal building directly across the street. [from SNCC Digital — read here.]

Directly across the street from the county courthouse in Selma was the federal building. On the first floor of that building was the office of the FBI, its windows looking out at the country courthouse. Standing on the street, witnessing everything that happened that day, were four FBI agents and two lawyers from the Justice Departments, one white, one Black.

By 11:40 a.m. no one could find a Black person who had come out of the courthouse who had actually gone through the registration procedure. I was standing with Jim Forman and another SNCC man when Sheriff Clark came over. “All right, clear out of here. You’re blocking the sidewalk.”

A man with sound equipment spoke to James Baldwin, whose eyes looked enormous, fiery. Baldwin waved toward the line of helmeted troopers. “The federal government is not doing what it is supposed to do.”

It was almost noon, the sun was beating down, and Forman was musing about the problem of getting water to the people on line, who had been standing there almost three hours. I looked across the street to the federal building. There on the steps were two SNCC fellows holding signs that faced the registration line. One of them, in overalls and fedora, had a sign saying, “REGISTER TO VOTE.”

I moved across the street to get a better look. As I did so, Sheriff Clark and three helmeted deputies came walking fast across the street. They went past the two Justice Department attorneys and two FBI men, up the steps of the building, and grabbed the two SNCC men. Clark called out, “You’re under arrest for unlawful assembly.” The deputies pulled the two down the steps and pushed them into a police car. A third man at the side entrance to the building, also holding a voter registration sign, was also arrested.

There could hardly be a more clear-cut violation of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits interference with the right to vote — to say nothing of the First Amendment’s right to free speech. And this had taken place on the steps of the U.S. government’s building, before the eyes of government men. I turned to the Justice Department man near me. “Is that a federal building?” I asked with some anger. “Yes,” he said, and turned away. The police car with the three SNCC men sped off.

Jim Forman told me that the night before he had wired the Justice Department for federal marshals, sure there would be trouble. The Justice Department had not replied.

Thank you for your insightful piece. I appreciated you thoughts on the women of the time. I believe I need to rethink how I approach the Civil Rights in my fifth grade classroom to include more women.