By greg wickenkamp

Between 1964 and 1972, 300 cities across the United States erupted in rebellion. Despite the scale of these rebellions, with more than half a million people participating, 60,000 arrests, and 250 deaths, their history is often flattened. These uprisings still shape our national identity and policies, but are often misremembered as irrational or rage-filled outpourings. “A considered analysis is urgently needed,” Jeanne Theoharis writes, “to grapple with the ‘structured blindnesses’ in this national fable.” Although Theoharis writes about the Civil Rights Movement (CRM), the uprisings, their distortions and omissions, are also central to this fable.

These rebellions’ origins are too often obscured. While the direct actions of the classic CRM resulted in some legislative gains, conservative pressures constrained them. Even as apartheid-like conditions remained in housing, employment, and social standing, new possibilities were imagined, and demanded. These conditions were accompanied by critiques the dominant society refused to adequately hear or respond to. For this reason, the “language of the unheard,” became in Dr. King’s words, “the riot.”

Militant turns in strategy and ideology challenged the failures of the Civil Rights Acts, even as the CRM’s precarious gains were undermined. Demanding more than voting rights or access to a hamburger, the uprisings were undeterred by that which threatened the CRM’s gains: white vigilantism; repressive state action (e.g., COINTELPRO); the rhetoric of white, corporate media; and, eventually, federal funding shifts from social uplift programs to the police and Pentagon. James Baldwin captured this frustration and militant shift, “Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?”

Seeing the uprisings more accurately means acknowledging they were not apolitical, stand-alone, or spontaneous expressions of rage. It means understanding them as participants did, as “the other side of the story to the civil rights movement that is never told.” These uprisings lifted up a demand often buried in the telling of the CRM, an insistence on a fully equitable society. Just as the CRM was international but misremembered as a Southern phenomenon, the uprisings were part of national movements. Like the CRM, their ideology and strategy resulted in pushback, but also in gains.

Rather than seeing the rebellions as spelling the end of the CRM, their real history reveals they initially won expansions in social welfare and redistributive programs. Conservative framing of them as apolitical or expressions of criminality encouraged, and still encourages, investments in militarized policing and the carceral state we know today. Bettering our society then depends on understanding these rebellions’ true history. This is not because history offers us a blueprint, as abolitionist Mariame Kaba writes, “but because it can help us ask better questions for the future.” Films can inspire good questions and insights about these waves of uprisings and their relevance for us today. What follows are my top five films for teaching about the uprisings, plus a handful of honorable mentions.

Top Five Films

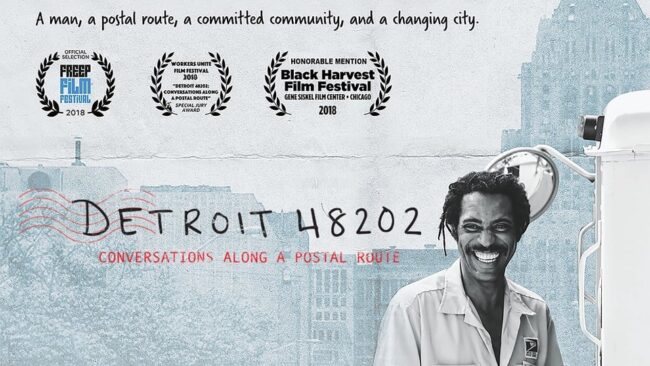

Detroit 48202: Conversations Along a Postal Route

Perhaps the best retrospective documentary film for middle and high school history courses is 2018’s Detroit 48202: Conversations Along a Postal Route. Wendall Watkins, an affable lifelong resident of Detroit, offers context to the changes he’s noticed along his delivery route. Although the film does not address Detroit’s uprising until its halfway point, the tight geographical focus allows for a thorough examination of its causes and effects and their connections to policing, housing, jobs, and politics. Engaging and entertaining, the film highlights accessible examples. It reveals the violence of the state’s response through the 152,000 rounds of ammo the National Guard fired at the city’s residents, cluttering the streets with so many bullet casings, children later made necklaces from them. The graffiti on Black-owned businesses identifying them as such so residents largely avoided their destruction makes clear that political aims informed even the riotous aspects.

The film offers a thorough examination of the causes of the rebellion, but also lessons we might learn from it. Showing racial capitalism’s unabated continuance in Detroit after 1967 challenges the culture of poverty myths that attempt to explain the uprisings then or poverty today. “It’s healing to children,” notes a resident, to learn that the poverty faced by many Detroit residents “is not [on them]” but a result of structures built by past generations. The film ends with mail carrier Watkins speaking to a group of elementary school children. After they ask about the abandoned buildings along his postal route, he delivers a package to one student. It contains the blueprints for nearby affordable senior housing. The students ask if the plans could be enlarged to include affordable housing for the whole community — a vision not far from what the so-called rioters demanded.

Riotsville, U.S.A.

The documentary that addresses the uprisings most directly, while providing the clearest and most accurate context, is Riotsville, U.S.A. The film focuses on a mock town, built in the late 1960s to aid law enforcement. This staged town, Riotsville, offered law enforcement the training and indoctrination that set the footing for the militarized policing we know today. Upper-level high school students can appreciate the film’s use of archival footage, and its presentation as an art house film as much as a documentary. Interspersed with archival footage are essays read over impressionistic visuals. These provide important analysis to support the masterfully curated and edited archival clips. With adequate context, excerpts of the film could be used even with middle school students.

The film offers a more nuanced exploration of the uprisings than even most critical histories, highlighting, for example, the 1968 Republican National Convention for being as formative to modern policing as the infamous Democratic convention in Chicago the same year. Some content might need scaffolding for students, as when Frantz Fanon’s work is referenced to explain the birth of the uprisings. Tapping the film’s literary richness might also require assistance — as when President Johnson, discussing the underlying causes of the uprising, is shown at the film’s beginning giving a warning to society. It would be a pity, he suggests with some eerie foreshadowing, to “settle for order that’s imposed by the muzzle of a gun.”

As much as the mock town “Riotsville” is a focus of the film, so too is the Kerner Commission. This exhaustive federal study outlined key policy recommendations to address the rebellions’ root causes. The Johnson administration, and the federal government since, has nearly entirely disregarded these recommendations. Instead, federal and state funding has invested in policing. Historical memory, including the still overlooked Kerner Commission, is brought into relief throughout the film, as when footage shows police rehearsing how to enforce order through violence. A voice reflects, “They’ve aged strangely, these images. They draw us in and freeze us. What to make of them now, embedded as we are in the future they were meant to ensure?”

Heard It Through the Grapevine

Focused more broadly on the legacies of the CRM, but also including the uprisings, is the brilliant and overlooked film, Heard It Through the Grapevine. Although for many students the film will feel dry and require additional background knowledge, its penetrating insight is hard to overstate. The film follows James Baldwin as he visits sites of the 1960s Civil Rights struggles and speaks with activists about the changes, or lack thereof, they’ve seen since. Visiting activists in Atlanta, Fred Shuttlesworth in Birmingham, Amiri Baraka in Newark, and activists in St. Petersburg, Florida, the film plays with space and time with the brilliance and eloquence one expects from Baldwin. Viewers watch President Johnson’s 1964 address with Baldwin, viewing the speech from 1982. As Johnson ends the address saying, “We Shall Overcome,” viewers see Baldwin’s wistful, faraway look. Viewers hear the announcement not as a pledge to work for justice, but as a pacifying deferment.

LBJ’s announcement allows viewers to understand that the federal response to the CRM was not about addressing specific anti-Black and violent policies, but rhetorically reducing that oppression to a vague existential ache, affecting everyone equally. The film touches on the growing carceral state that emerged following the CRM, the broader neocolonialism from which anti-Blackness took root, poverty as an immoral and solvable crisis, and the destructive identities a nation predicated on white supremacy imbues. More than the occasional slur or swearword, and more than the anti-Black physical violence depicted in the film, the background knowledge the film assumes of the viewer leave this film best suited for advanced high school or undergraduate courses. Regardless of classroom use, every educator and citizen should watch it.

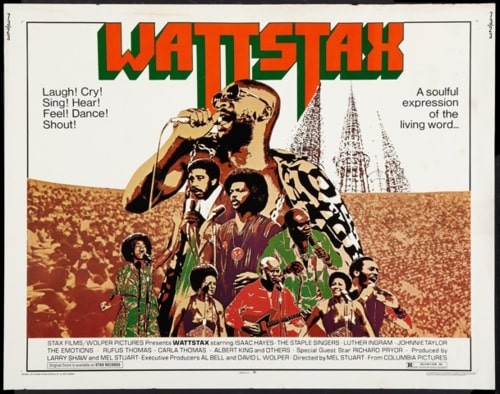

Wattstax

An excellent documentary is 1973’s Wattstax about a mostly forgotten concert with 112,000 attendees, perhaps, the film claims, the largest gathering of Black people in the United States outside a civil rights event at that time. Filmed on the seventh anniversary of the Watts’ uprising, it uses an anniversary concert to grapple with the uprisings’ enduring legacies. As the film weaves together concert footage with jokes from Richard Pryor and casual conversations amongst Black Watts residents, the film deftly touches on major themes of the uprisings. The music highlights the uprising’s legacies, the consciousness raising, the role of religion, and the degree to which uprisings represented a continuation or break from earlier civil rights struggles. A montage over the lyrics “what you see is what you get” reflects the urgency and tumult of the period in a way similar to the short film Now! another artistic overview. During one scene in Wattstax, residents ask if the uprising made things better. They cite specific political and community action programs that resulted from it, but also the rising backlash against such programs. The question is left unresolved, but residents seem to agree that the uprisings were “the only way we could communicate with whitey.” Some of this film is crude, but excerpts can be useful for upper level middle or high school classrooms.

The Urban Crisis and the New Militant Series

In a relatively obscure set of film modules recorded between 1966 and 1968, a Chicago-based production company wanted to “teach by raising questions rather than by attempting to answer them.” These modules, The Urban Crisis and the New Militant Series, are roughly 10 minutes each, preserved by the Chicago Film Archives in the early 2000s. The production company behind them were radicalized by the cracks made to Jim Crow, which prompted their turn from commercial work to documenting the streets. The series reflects the raw radicalism of the time period, produced as a passion project by the production company’s accountant. While most students will require additional contextualizing resources to make sense of these modules, excerpts from this overlooked series can be useful in high school classrooms.

Its modules are particularly effective at showing the white backlash to the CRM. Two modules in particular reveal what this backlash looked like through both vigilantism and policing. The first module focuses on the protests surrounding the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Viewers see activist leaders attempting to work with city officials to make a safe plan for the thousands of anticipated protestors. Instead of city officials working with the public to ensure safety, the footage shows 30,000 military personnel placed on high alert. The beatings and violence that followed may be too graphic outside of upper-level high school classrooms.

Showing a precursor to the uprisings, the seventh module reveals northern racists’ refusal to integrate society. Dr. King joins a locally led march to integrate an all-white Chicago suburb, Cicero, in 1966. White children and their suburban families hold signs with swastikas that read “white power” as they yell and chant, “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate!” This level of unmasked anti-Black hatred is often obscured, whether in the silences of historical narratives or by playing out through structures and systems instead of interpersonal interactions. Much of the footage in the module from Cicero comes from a feature-length documentary project by the same company, American Revolution 2. This and the company’s 1971 documentary, The Murder of Fred Hampton, offer compelling excerpts that might be useful in the classroom as primary source materials.

Honorable Mentions

Other documentaries can be useful in exploring the uprisings. CBS made two films immediately following the uprising in Watts: 1965’s Watts: Riot or Rebellion, and 1966’s Black Power White Backlash. They show how media passing itself as objective might be sympathetic to a white supremacist social order. In the 1966 film, the violence of the all-white Cicero in resisting housing integration is couched by a narrator describing the town as one where “people took care of themselves,” had “pride in property,” and “just want[ed] to be left alone.” With this, the 1966 pressure to integrate housing is framed as an affront, rather than the slow structural violence of exclusionary housing or the swift violence of white vigilantism when that exclusion was challenged. Similarly shaped by a white gaze is Black Power White Backlash, which nonetheless offers useful excerpts for the classroom. Kwame Ture, Martin Luther King, Daniel Watts, and white children of Cicero offer compelling interviews ripe for classroom use and analysis. One white teenager says, “There are many good coloreds” but he can’t stand the ones who march. Author Daniel Watts connects intersecting oppressions, presciently noting that unless their root causes were addressed, the uprisings of the mid-1960s would be a “prologue.”

The short documentary films Felicia and Teddy offer a more critical, if less narrative-driven, perspective. Felicia, filmed before the Watts rebellion, has rarely been seen outside of film studies courses, especially before its 2014 adoption to the National Film Registry. Following closely the life of young Felicia, the 13-minute film addresses issues of race in a rare, “personalized and intimate mode.” Felicia’s experiences speak to oppression in housing, employment, and especially education. Teddy, filmed after the Watts uprising, touches on differences of strategy that became sharp as Black Power eclipsed respectability politics. A young man, Teddy, decides whether to join the Black Panthers, busy implementing free breakfast and community programs as they study Mao’s Little Red Book. This short film shows the uprisings led to significant changes in both material conditions and consciousness.

While primary source documentaries can sometimes be too slow paced to maintain student interest, historical fiction can be useful. Especially when time allows students to critically examine a fictionalized film along with more accurate resources, the process of historical memory can be made plain. Sam Greenlee’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door shows the appeal of militant action when other doors are closed. Like Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, the film is too adult for general classroom use, but excerpts might be useful. Similarly, the film Detroit on the city’s 1967 uprising lends itself to analysis. One longtime Detroit resident claimed the film is “99.5 percent accurate,” while another notes the film’s most poignant lesson is not on the uprising itself, but the “white way of thinking” about it.

Histories as complex and often distorted as those of the rebellions of the late 1960s and ’70s must be taught with nuance. It is not enough to show students footage of the “rivers of fire, 10 blocks long” that raged through Detroit in 1967. Students must have a chance to make sense of the fires that engulfed Watts, Newark, and hundreds of other cities, as well as the coals which continue to shape our present. Real learning means asking questions and engaging deeply with our society’s history. As educators, we have the awesome responsibility of allowing students to be shaped by their past. “The learning process,” then, as Audre Lorde reminds us, “is something you can incite, literally incite, like a riot. And then, just possibly, hopefully, it goes home, or on.”

greg wickenkamp is a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Iowa. His current work builds on curiosities that arose over more than a decade of K-16 social studies education, particularly around history’s relationship to identity, race, and social justice. He has co-coordinated the annual Teach Truth Day of Action in Iowa and wrote Op-ed: Conservative politics depend on disremembering. Read more.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn