In this remarkable graphic novel, writer and illustrator David H. T. Wong tells us that the Chinese didn’t distinguish between Canada and the United States when they referred to Gam Saan (Gold Mountain — the Chinese term for North America).

In this remarkable graphic novel, writer and illustrator David H. T. Wong tells us that the Chinese didn’t distinguish between Canada and the United States when they referred to Gam Saan (Gold Mountain — the Chinese term for North America).

That blending of U.S. and Canadian history is one of the delightful and unusual aspects of this important book. Told as the history of the Wong family, this accessible volume offers readers a panoramic but also an intimate look at the Chinese experience in North America.

No doubt, this is a story of racism, exploitation, and violence; but it’s also a story of warmth and solidarity. [Review by Rethinking Schools.]

ISBN: 9781551524764 | Arsenal Pulp Press

For more information, visit Arsenal Pulp Press.

Reviews

Wong’s book is a great illustrated yarn — make that several generational yarns woven together — telling the story of Chinese families coming to North America (or “Gold Mountain” as those immigrants called this continent). Wong doesn’t flinch from showing the discrimination and hardships Chinese faced as they sought to build new lives here, nor does he neglect the triumphant contributions they have made. Told and drawn with humor and bravado, this is a no digest of historical facts. It’s a page turner for all ages that is likely to become a classic. — The Tyee

Although the comic-book format makes some serious moments darkly funny, one reads with horror about atrocities once commonplace in our backyard. — Seattle Weekly

Wong proves that pictures can indeed hold thousands (and thousands!) of words, capturing 200+ years of history in as many pages; he also includes a “Chinglish” glossary, a timeline that overlaps China and Gam Saan, maps, extensive notes, and a thorough bibliography. — Book Dragon blog from the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

This book is an excellent introduction to the complex issue of Chinese immigration as told from the Chinese point of view. — Seattle Post-Intelligencer

If you want to read about a shameful chapter of American history in convenient comic-book form, you should read Escape to Gold Mountain. — The Stranger

Escape to Gold Mountain is an important book that plays to the strength of the graphic novel form. It encapsulates the struggle of the Chinese in North America in a sweeping visual narrative, attacking a complex storyline that takes in the opium wars to early immigration, railroad workers, the head tax, and the Chinese exclusion act. Forget Batman; Escape to Gold Mountain reveals that the real superheroes are the ones who toil and sacrifice for their families in the face of obscurity. — Tony Wong, journalist

Eloquent, lyrical black-and-gray panels that conjure the environment and living conditions as well as the people. — Library Journal

Classroom Story

Based on her use of Escape to Gold Mountain, teacher Lorena German shared her reflections on teaching about anti-Asian racism.

I taught young people in Austin at a predominantly white institution in the heart of downtown. At our school, we often had several exchange students from Asian countries. Teaching them was a blessing and just like our other students, they brought a richness and depth to our school community. Our school prided itself on being supportive, thoughtful, and inclusive. We certainly were, to an extent. Racial microaggressions were something that happened often, both at our school and in Austin, Texas, so there was work for all of us to take on and conversations for us to have. We see how in 2021 anti Asian bias morphed into anti Asian hate and that became anti Asian violence. For my students, understanding the complexity of racial microaggressions, the experiences of Asians, immigrants, and Asian Americans began in our 9th grade literature course. I used the best tool I know: books.

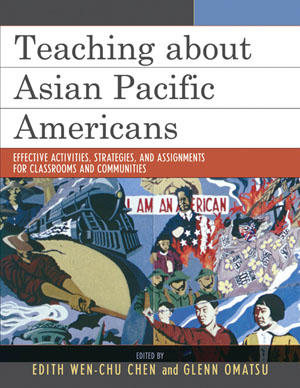

After building relationships and community as a class, we would get into conversations about key terms such as microaggression, stereotypes, racism, and other related concepts that will surface in the unit. After those structured discussions, we would turn to the historical fiction graphic novel, Escape to Gold Mountain by David H. T. Wong, which I learned about through the Zinn Education Project. Escape to Gold Mountain allows us to develop and expand our background knowledge before jumping into the core text. In it, we learn about the racist history of the Chinese immigration experience. We learn about how the Chinese have been here for many, many years, their important contributions to this country, and the ways that our society has openly rejected them. I also teach early poems from Chinese immigrants as well as modern writings from the book Becoming Americans, an anthology focused on the stories of immigrants.

These conversations and these texts provide the historical context we need to dive into a literary analysis of our core text, American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang. It’s a modern and touching graphic novel exploring issues of Chinese American identity through the fictional character of Jin. It has a powerful storyline that reveals the ways young people struggle with racial conformity as a means of social survival, among other topics. Both American Born Chinese and Escape to Gold Mountain focus on the history of Asians in the United States and the role race(ism) has played in their collective experience here. They both also happen to be graphic novels, which is a great opportunity for teachers to engage in a visual literacy and rhetorical study.

Continue Reading

During the study of American Born Chinese, we would visit my friend Dr. Richard Reddick at the University of Texas at Austin. We would participate in a panel-style presentation where he would help us learn about the complexity of the model minority myth and the ways it operates as a form of anti-Blackness. Although the book doesn’t explicitly explore this topic, I used this unit to surface the conversation and engage students in talking about this important issue. Again, considering our social context and the student body, I knew this was a conversation that was needed. Dr. Reddick would explain:

- History of the model minority myth

- The history of anti-Asian and anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States

- The model minority myth as a form of anti-Blackness

- What the term Asian truly encompasses (nations and people groups)

That would always be a very revealing session and students would share how eye-opening the conversation was. When we finished reading the book, before we engaged in our final assessment, there was one more speaker. I would host a speaker who identifies as Chinese or maybe from another Asian country, and they share their story of facing racial bias with our class. They would share experiences with racial microaggressions and how they dealt with it. One year, my Chinese American friend spoke of how her parents came to this country for educational purposes and were discriminated against which led them to explicitly not teach their children Mandarin so they wouldn’t experience the same struggles. She talked about culture, family, pressures, and the subtle (and not so subtle) microaggressions she experienced growing up in a predominantly white suburban town in New Jersey. One year, one of our exchange student’s fathers was visiting from China and she wanted him to share about the Monkey King referenced in Yang’s text. I chose to welcome him because it was important for my white students to see this immigrant man as an intellectual source of information and expert in the content we were studying. All of these speakers would bring the text to life and make these issues relevant to my students’ lives.

After we’d finished reading the book, we completed an essay required by our school’s department. In this essay, students were able to explore and write about any topic surfaced throughout the unit’s discussions. These essays were powerful and it was encouraging to see the students interested in learning deeply about anti-racist ideas. Some of the strongest lines from students’ work in the past years are quoted here:

Yellowface mutated the image of Asians into racist cruel jokes and whitewashing made them invisible to audiences. — Grade 9, 2017

Our culture puts a lot of stress on Asian-Americans to be quiet, polite, and not to have attention drawn to them. — Grade 9, 2016

The Model Minority Myth is exactly that — a myth. It is untrue, insensitive, and a method for casual racism. — Grade 9, 2016

Unlike explicit biases, people are often unaware of their own implicit biases and because of this many racist ideas and stereotypes are instilled in us. If this continues, the racism that people of color already face in their everyday lives will be multiplied as time goes on. — Grade 9, 2016

This unit was one of my favorites in my ninth grade curriculum. As an immigrant woman of color, it brought me hope to share a bit of myself with these young people who were generally different than I was and might not relate to my experience at all, but welcomed the information with empathy. While I’m not Asian or Asian American, as a Dominican immigrant I can relate to the feeling of otherness as well as feeling harassed because of my perpetual foreigner status although I’m a citizen and have lived here since I was four. I was encouraged when they rejected the hate that was expressed to marginalized groups and I was motivated by their collective anger and frustration at our country’s historic patterns. The best part of all is when they would begin to make connections between the past and the present and slowly become critical thinkers and activists in their own immediate spaces.

In 2019, it was especially relevant as they made connections between the Japanese internment camps (also discussed in this unit) and the current crisis of children and adults in cages at the border. It was especially relevant as they heard the same rhetoric used in the late 1800s resurface and become national rhetoric all over again in 2019. Students also often share frustration and concern about the ways that our country has historically treated immigrants and it creates a sense of awareness for them of the harm that’s done by phrases and thinking such as “they’re taking our jobs” or “ban them.” Not addressing history with our young people is a form of deceit. Not telling them the truth of the past irresponsibly denies them the knowledge and skills to function well in the present. For ELA teachers, books are a powerful avenue for this truth telling and truth teaching.

References

Stavans, Ilan, and Pete Hamill. Becoming Americans four centuries of immigrant writing. New York: Literary classics of the United States, 2009

Takaki, Ronald T. Strangers from a different shore: a history of Asian Americans. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1998.

Wong, David H. T. Escape to gold mountain: a graphic history of the Chinese in North America. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2012.

Yang, Gene Luen., and Lark Pien. American born Chinese. New York: Square Fish, 2010.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn