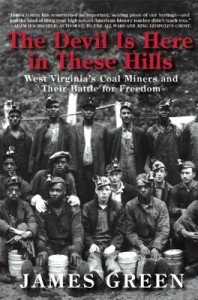

From before the dawn of the 20th century until the arrival of the New Deal, one of the most protracted and deadly labor struggles in U.S. history was waged in West Virginia. On one side were powerful corporations whose millions bought armed guards and political influence. On the other side were 50,000 mine workers, the nation’s largest labor union, and the legendary “miners’ angel,” Mother Jones. The fight for unionization and civil rights sparked a political crisis verging on civil war that stretched from the creeks and hollows to the courts and the US Senate. In The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom, historian James Green tells the labor history of West Virginia coal miners.

From before the dawn of the 20th century until the arrival of the New Deal, one of the most protracted and deadly labor struggles in U.S. history was waged in West Virginia. On one side were powerful corporations whose millions bought armed guards and political influence. On the other side were 50,000 mine workers, the nation’s largest labor union, and the legendary “miners’ angel,” Mother Jones. The fight for unionization and civil rights sparked a political crisis verging on civil war that stretched from the creeks and hollows to the courts and the US Senate. In The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom, historian James Green tells the labor history of West Virginia coal miners.

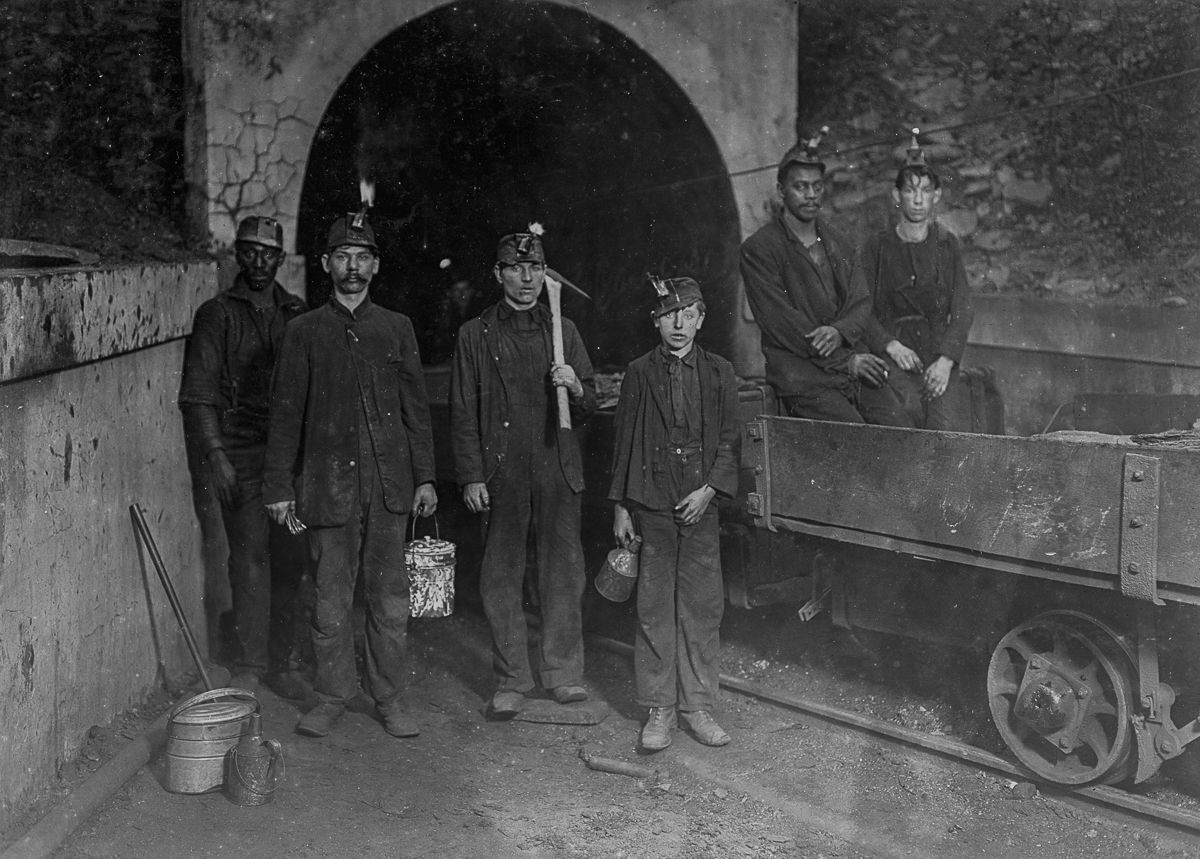

The value of West Virginia’s coalfields had been known for decades, and after rail arrived in the 1870s, industrialists pushed fast into the wilderness, digging mines and building company towns where they wielded nearly complete control over everyday life. The state’s high-quality coal drove American expansion and industrialization, but for tens of thousands of laborers, including boys as young as ten, mining life showed the bitter irony of the state motto, “Mountaineers are Always Free.” Attempts to unionize were met with stiff resistance. Fundamental rights were bent, then broken, and the violence evolved from bloody skirmishes to open armed conflict, as an army of miners marched to an explosive showdown. The Devil Is Here in These Hills is extensively researched and told in vibrant detail. [From the publisher’s description.]

ISBN: 9780802123312 | Atlantic Monthly Press

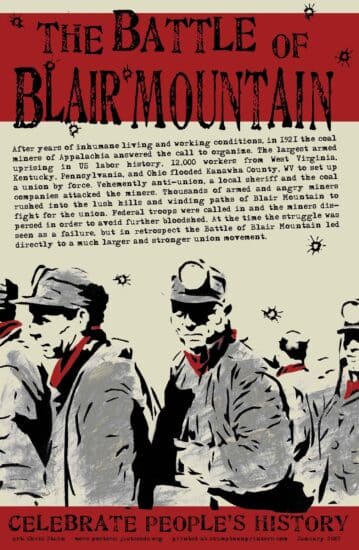

The Battle of Blair Mountain

Description by the author of one of the key events, the Battle of Blair Mountain, featured in the book.

By James Green

August 31 marks the anniversary of the largest civil insurrection in U.S. history after the Civil War. This uprising, which has been all but lost to memory, was the climax of two mine wars fought in the West Virginia coalfields from 1912—1921.

At a time when many citizens are worrying about “economic inequality,” when conservatives are bewailing the use of “class warfare” language, when “insurgents” are still being imprisoned without due process, when police forces in poor communities are being privatized and militarized, when banks are ordering evictions, it is worth discovering, exploring and understanding the West Virginia mine wars — a profound but largely unknown expression of class struggle.

Armed insurgency erupted in the coal mining counties of southern West Virginia in late August of 1921, when an army of more than 8,000 rifle-bearing union miners marched toward Mingo County on the Kentucky border. They intended to liberate other miners and their families from the tyranny imposed by private mine guards who had terrorized the region for more than a decade, and from a regime of martial law imposed by the governor.

Map of the West Virginia Mine Wars that accompanies the CD, “Blair Pathways: A Musical Exploration of America’s Largest Labor Uprising.” Source: Blair Pathways.

Armed warfare erupted on August 31, 1921, on Blair Mountain in Logan County when the miners’ army clashed with armed forces marshaled by the county sheriff, the coal companies and the state police.

The three-day Battle of Blair Mountain was the climax of a war that had rocked West Virginia since the early years of the twentieth century when the United Mine Workers, led by Mother Jones, tried repeatedly to penetrate tightly controlled company coal towns.

In the spring of 1912, union miners struck in the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek region near Charleston after they were evicted from company houses, and then suffered armed assaults on their encampments by private police. Twelve strikers and thirteen company men died in the first West Virginia 13 month struggle that verged on civil war.

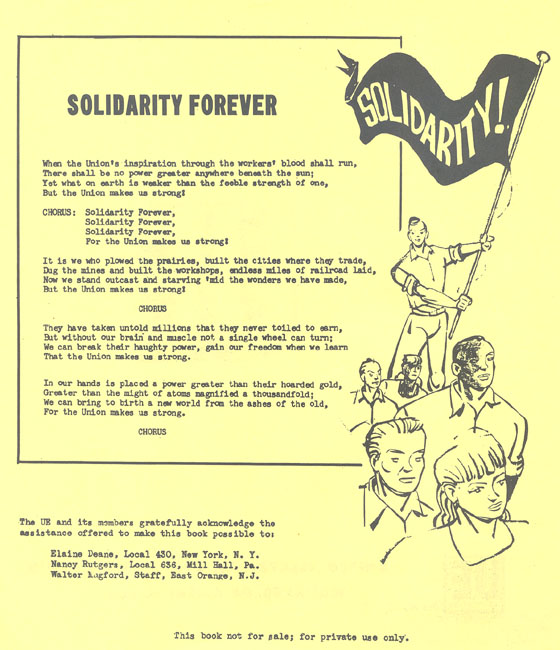

The strikers’ solidarity held firm across racial lines and inspired the poet Ralph Chaplin to write “Solidarity Forever,” the song that eventually became the anthem of the U.S. labor movement.

A second mine war threatened on May 19, 1920, as a result of a sensational shoot out on the streets of Matewan in Mingo County where the pro-union sheriff, Sid Hatfield, and his deputies killed seven private detectives who had evicted scores of striker families from their homes. The gun battle made the front page of the New York Times and made Hatfield a notorious celebrity. (John Sayles dramatized these event in his gripping 1987 film, Matewan.)

Skirmishing continued until the summer of 1921 as union organizers tried to penetrate the company-dominated Mingo County on the Tug River, the state’s western border. In response, the governor declared martial law in that strife-torn county. As a result, scores of union men were imprisoned and held incommunicado. The governor’s declaration of martial law created a furious reaction among unionized coal miners in other parts of the state.

On August 20, hundreds of miners gathered at Lens Creek south of the capitol, armed and ready to march on Mingo County to liberate the union men imprisoned under the martial law decree.

The next day’s headline of a front page story in the New York Times read: “Terror in Mine Area as 4,000 Armed Men Move Toward Mingo.” An “army of malcontents”, composed of union miners and “not a few ex-service men”, were, the story continued, engaged in a violent protest against the “mine guard system” that had long prevailed “in the troubled region.” It was further reported that insurgents commandeered passenger trains, cut telephone wires, looted coal company stores of arms and ammunition; and executed two alleged company spies. President Harding, eager to escape the sweltering White House for an August cruise was forced to stay on and meet with senators and generals in the War Department, because, he was informed that West Virginia was on the brink of civil war.

To reach Mingo, the union forces had to cross over Blair Mountain and pass through Logan County, where it was reported that “wild alarm” spread through the area with news of the coming in invasion. In response, Sheriff Chafin mobilized a small army of 3,000 deputies to stop invaders. On August 30, Harding issued a proclamation ordering all persons engaged in “insurrectionary proceedings to disband” in two days. The order never reached the armed miners.

On August 31, the two forces collided and the mountain valleys reverberated with rifle and machine gun fire for two days.

UMW officials and members of the “miner’s army” display a bomb dropped on them during the Battle of Blair Mountain. Source: West Virginia State Archives.

The arrival of battled-tested U.S. Army troops finally put a stop to the battle. The insurgent miners said they were willing to surrender to “Uncle Sam” and let the U.S. Army put an end to fighting. But they would never surrender to their sworn enemies — the coal operators and the men they hired to do their heavy work. Even though they failed in their strategic objectives, the union miners believed their armed march had called the nation’s attention to the state of terrorism they had endured for so many years in West Virginia company towns.

It soon became clear that the union miners could claim no final victory in this quasi-civil war. Their insurgent leaders were put on trial for treason, the hated mine guard system and all the abuses in protected were kept in force, and the union was driven underground.

Twelve hard and bitter years passed before the union resurfaced in West Virginia during the time when a social earthquake rocked the nation. Then, in the first years of the great depression, the leaders of the miners’ march of 1921 reappeared and began to revive what the writer Edmund Wilson called the “unbroken spirit” of the West Virginia miners.

James Green is the author of The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and their Battle for Freedom (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2015). The book is the basis of a two hour PBS American Experience film, The Mine Wars, first broadcast in 2016.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn