An artist prepares his graffiti with the inscription on a wall in the slaughterhouse district in Munich, Germany. Source: Peter Kneffel/dpa via AP

By a DCPS middle school teacher

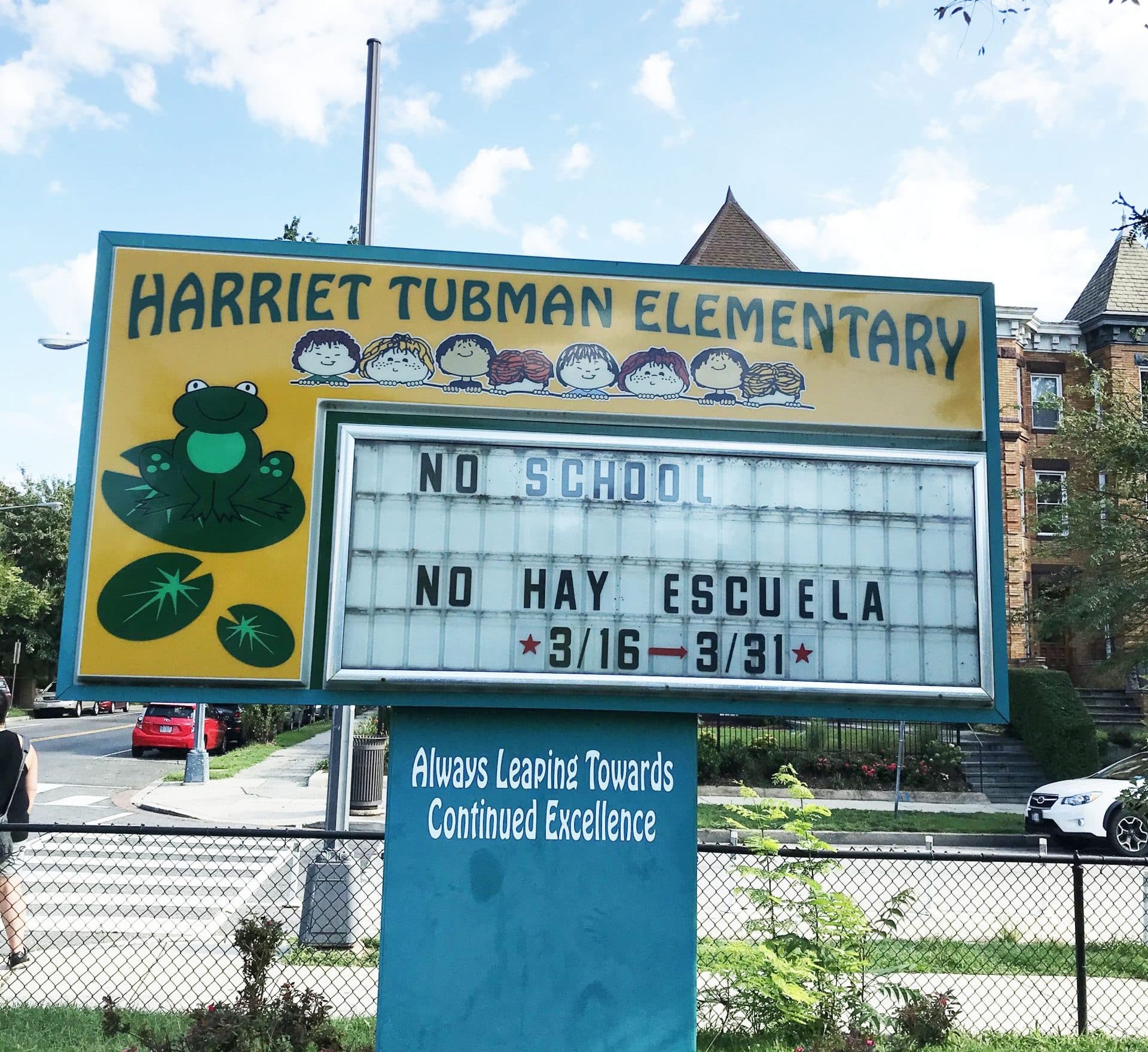

By March 13, the last day of in-person classes in Washington, D.C., I had moved all desks in my classroom six feet apart and encouraged students to remain calm, use hand sanitizer, have empathy for other teachers and students, but to take precautions.

By March 13, the last day of in-person classes in Washington, D.C., I had moved all desks in my classroom six feet apart and encouraged students to remain calm, use hand sanitizer, have empathy for other teachers and students, but to take precautions.

It was clear to my students, who live in every region of the city and are overwhelmingly students of color, other teachers, and the entire staff at Hardy Middle School that the coronavirus, coupled with a lack of response or preparation, would change our lives for the unforeseeable future. . .

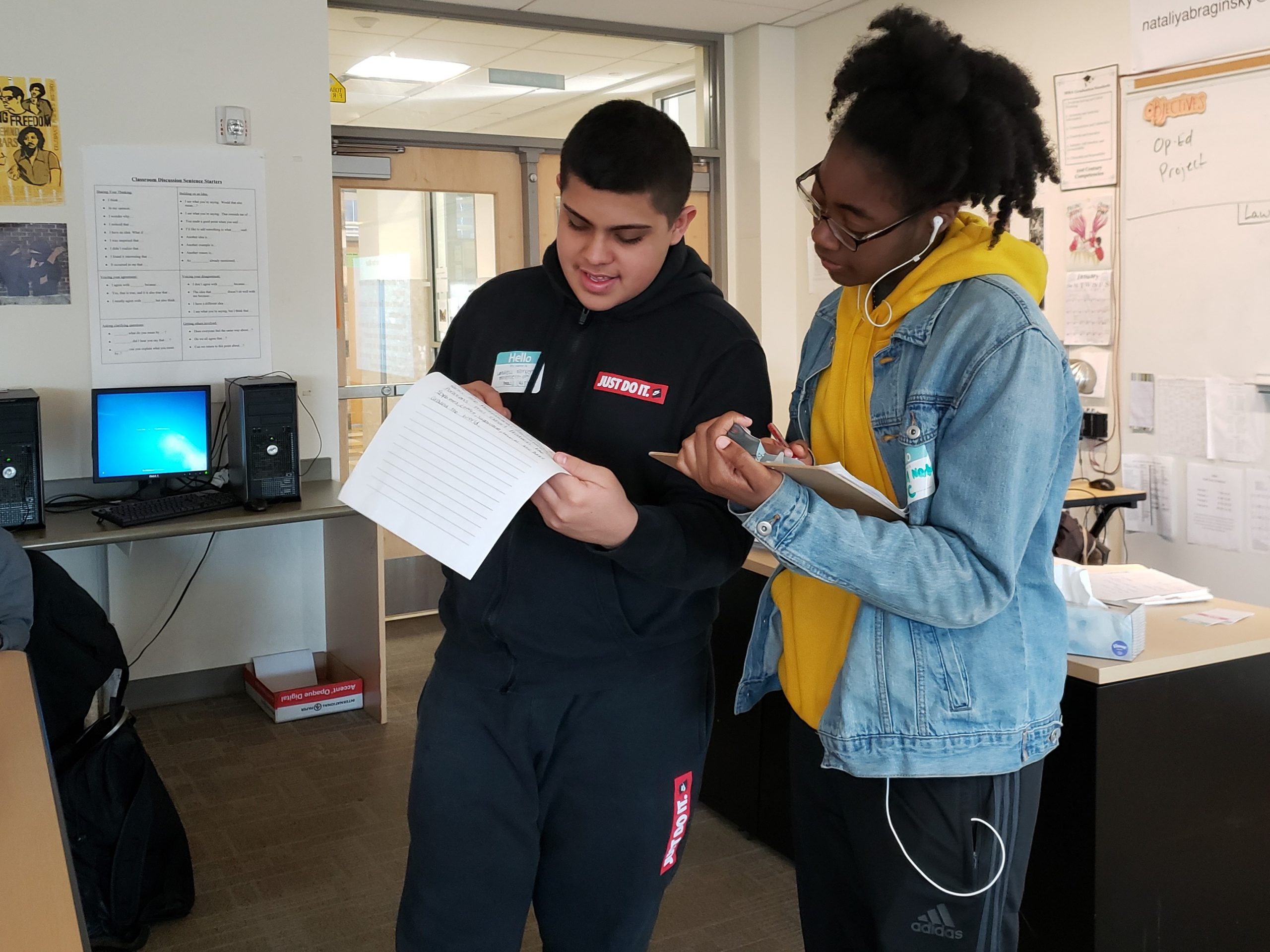

I originally planned to complete a culminating group discussion on the Indian Removal Act, using the Cherokee/Seminole Removal Role Play at the Zinn Education Project. But I also knew my students were being inundated with more articles, graphs, and research on the pandemic. Xenophobia was also on the rise as people across the country used racist language to describe the coronavirus. I wanted to do whatever my students wanted to do.

So I asked them.

I had students take a survey during the first week of April on whether we should talk in more detail about the Indian Removal Act or hold a tribunal on the coronavirus. Fifty-four out of the 60 students in class that day said let’s have a tribunal on who’s to blame for the crisis in the United States.

I chose to write a tribunal, rather than a mixer lesson or research-based activity, as the students had already mentioned that the tribunal on Columbus found in the Rethinking Schools book Rethinking Columbus was one of their favorite lessons of the school year. In addition, by March, I knew that my students’ generation was being blamed for something they were not responsible for — their own death and oppression. So I wanted to write a lesson to help them formulate their own language to fight back.

Students commented that information about the coronavirus was everywhere, and they felt overwhelmed. But were they overwhelmed with the same information? Was the information accurate? Was the information racist? I wanted to consider the fact that my students come from 13 different elementary schools and live in every ward in the District of Columbia. I could not just tell the story with different news items. I wanted to create a lesson to empower them to tell their story to me and to others. What did they know? What had they read? And how was it affecting their understanding of this crisis? What was wrong in society and how should we change it?

And that was the most important part of this lesson: students writing a 10-point program — inspired by the Black Panthers’ 10-point program, adopted in 1966 — on how to prevent crises like this in the future.

I asked students how it compared to other trial lessons (Columbus, Reconstruction, etc). This one does require more media literacy and research than the others, but in the words of one student: “It was easier because I have been thinking about who is to blame for months.”

— Tracey Barrett (@traceyebarrett) March 25, 2021

TEACHERS: We’d love your feedback after using this lesson. Submit your reflections, student comments, modifications, questions, and more. In appreciation for your story, we will send you a free copy of the Rethinking Schools book, Teaching for Black Lives.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn