In this groundbreaking history of the modern American metropolis, Richard Rothstein, a leading authority on housing policy, explodes the myth that America’s cities came to be racially divided through de facto segregation — that is, through individual prejudices, income differences, or the actions of private institutions like banks and real estate agencies. Rather, The Color of Law incontrovertibly makes clear that it was de jure segregation—the laws and policy decisions passed by local, state, and federal governments — that actually promoted the discriminatory patterns that continue to this day.

In this groundbreaking history of the modern American metropolis, Richard Rothstein, a leading authority on housing policy, explodes the myth that America’s cities came to be racially divided through de facto segregation — that is, through individual prejudices, income differences, or the actions of private institutions like banks and real estate agencies. Rather, The Color of Law incontrovertibly makes clear that it was de jure segregation—the laws and policy decisions passed by local, state, and federal governments — that actually promoted the discriminatory patterns that continue to this day.

Through extraordinary revelations and extensive research that Ta-Nehisi Coates has lauded as “brilliant” (The Atlantic), Rothstein comes to chronicle nothing less than an untold story that begins in the 1920s, showing how this process of de jure segregation began with explicit racial zoning, as millions of African Americans moved in a great historical migration from the South to the North.

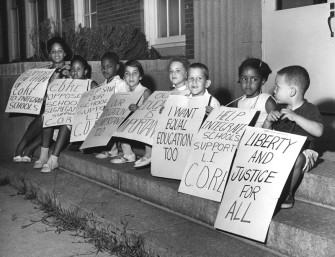

As Jane Jacobs established in her classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it was the deeply flawed urban planning of the 1950s that created many of the impoverished neighborhoods we know. Now, Rothstein expands our understanding of this history, showing how government policies led to the creation of officially segregated public housing and the demolition of previously integrated neighborhoods. While urban areas rapidly deteriorated, the great American suburbanization of the post-World War II years was spurred on by federal subsidies for builders on the condition that no homes be sold to African Americans. Finally, Rothstein shows how police and prosecutors brutally upheld these standards by supporting violent resistance to Black families in white neighborhoods.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited future discrimination but did nothing to reverse residential patterns that had become deeply embedded. Yet recent outbursts of violence in cities like Baltimore, Ferguson, and Minneapolis show us precisely how the legacy of these earlier eras contributes to persistent racial unrest. “The American landscape will never look the same to readers of this important book” (Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund), as Rothstein’s invaluable examination shows that only by relearning this history can we finally pave the way for the nation to remedy its unconstitutional past. [Publisher’s description]

ISBN: 9781631492853 | Liveright

Teacher Testimonials

When our school district embarked on an equity initiative, some teachers had struggled to put it into practice. The initiative builds from the idea that ALL students are welcome as they are and that ultimately ALL students are provided tasks that demand production at higher levels of depth of knowledge (DOK3/4) so that they can communicate like a scientist, mathematician, historian, etc. The “meeting all students as they are…” aspect of the district initiative has been challenging.

To overcome the challenge, I worked with several high school history teachers as an instructional coach and The Color of Law has been eye opening for them. Groups of educators in the district gathered to read excerpts from Color of Law together and reflect on the history of segregation. It helped them collaboratively expand their lessons beyond the textbook and spark more interest all our students.

There are teachers who have lifted excerpts directly from The Color of Law and had students read them alongside the traditional textbook account of the New Deal. We’ve also begun to design activities that allow students to do some of the investigation of dejure discrimination and segregation right here in San Jose, California. The local library has quite a few online resources and our librarians are getting involved as we try to make our Gale Database more student accessible. One of the findings is the Chinatown that was once in the center of downtown and now is buried under the Fairmont Hotel. It’s truly becoming a collaborative project across our staff. We’re looking forward to more discoveries by students who are not only getting a “people’s perspective” but also finding history interesting and important today.

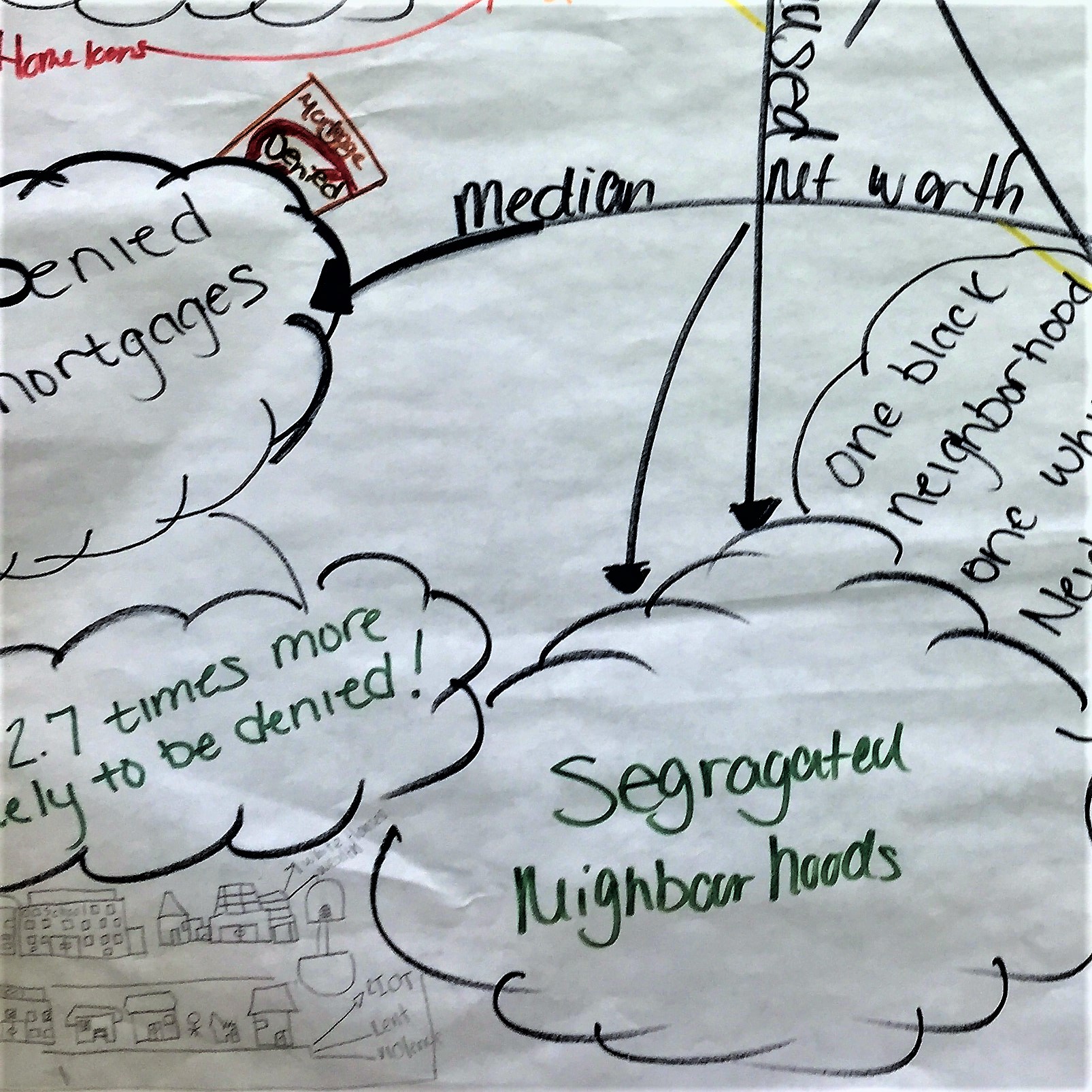

I use excerpts from The Color of Law in addition to excerpts from Thomas Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis to teach about dejure housing discrimination and segregation. Specifically, we focus on the relationship between the government, banks, neighborhood associations and the wealth discrepancy between the races that we see today.

To demonstrate this connection, scholars read sources and develop a “mind map” that shows the relationships. This is especially relevant in Detroit, which has one of the most interesting and volatile history of racialized housing segregation. We start out with general questions that raise scholars already-existent awareness of the issue such as, “where are the best public schools in the area?” “where do people of different races live?” “where are the racial boundaries in Detroit?”

Building on this knowledge, students then come up with their own questions.

Students’ questions were “how did neighborhoods get segregated?” “why does housing segregation affect school quality?” This naturally led to diving into the texts to answer these questions, looking at demographic maps pre- and post-1967 Detroit rebellion, and reading primary source pamphlets from white neighborhood associations. These issues impact the classroom.

By the end, students realized that segregation was not of individuals choosing necessarily, but rather a planned, coordinated effort by the institutions that exist in the U.S. to keep people separate and to keep the dominant group dominant.

I teach two college courses at South High School in Denver and The Color of Law has been instrumental in discussing housing discrimination and segregation.

In African American history, the intentional government policies that impacted generations of Black and Latino Americans still impact Denver today. We also discussed the book in relation to the Keyes v. Denver (1973) case and subsequent desegregation of Denver Public Schools. Neighborhoods and suburbs in Denver following that decision have left schools more segregated than ever. The concept of community or neighborhood public education is heavily influenced by housing discrimination. Students were engaged and really enjoyed diving deeply into this concept.

This book led to a student-led project idea that we will develop in Denver. Students want to interview residents who were impacted by discriminatory practices and talk about how it has shaped their experiences. Additionally, they want to look at the South High School classes of 1973, 1974, 1975, and 1976 during the first years of busing to talk about how students, teachers, parents, and community members responded to the integration of schools. The Color of Law sheds light on the problems that many cities and communities face today as a result of decades of housing discrimination.

Read more 'Color of Law' classroom stories

Every Spring in my American History classes, I teach our sophomores about the history of housing discrimination and segregation in and around American cities during the 20th Century. I always have the students read an NPR article that excerpts an NPR interview with Richard Rothstein. He succinctly and effectively makes the case that The Color of Law outlines. Housing discrimination and segregation in American cities is a result of de jure, rather than de facto segregation. Rothstein also explains the history and meaning of the word, ghetto, which my students find fascinating.

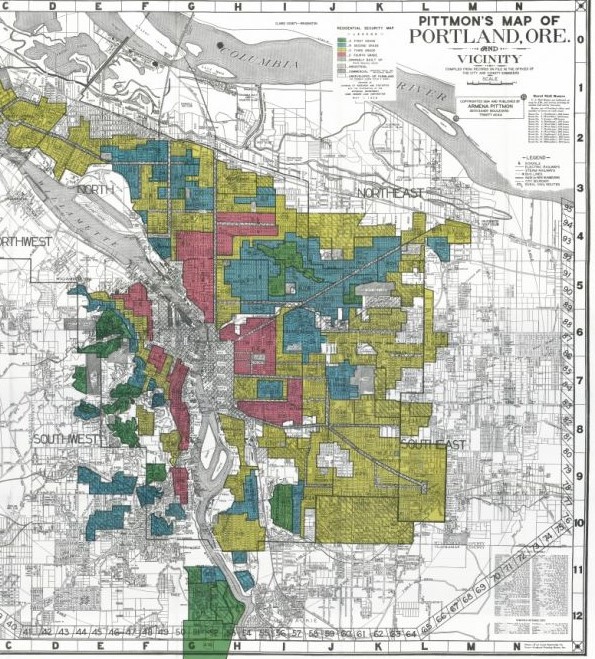

We are a diverse school in Central Illinois, a few hours from Chicago. Our community is closely linked to Chicago, with students and staff having relatives in Chicagoland, or experience living in the city. I have the students explore an online resource of compiled redlining maps from 20th century Chicago, and then we compare these to the current racial dot map of Chicago. This leads the students to want to investigate whether any redlining or other nefarious hiding discrimination still exists. We then begin an inquiry-based search for recent example of housing discrimination, even beyond racial housing discrimination. The Rothstein article is a good jumping off point for a popular lesson.

In my AP English Language class, which focuses on non-fiction, I use several texts to explore systemic injustices including The Color of Law. I use excerpts from Chapter 4, “Own Your Own Home” in conjunction with Chapter 4 from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and ask students to compare how Jurgis and his family suffer exploitation with what happened to African Americans.

I use period pamphlets and maps, particularly redlining maps, so the students can study them using graphic organizers from the Library of Congress or National History Day. It’s important for the students to explore the documents within the framework of Rothstein’s text and a guiding set of questions rather than have me tell them what they’re seeing.

I also incorporate excerpts from Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow to compare the explicit government regulations that result in systemic racism with Chapter 5, “Private Agreements, Government Enforcement.” We examine government statutes to determine what the law actually says, as opposed to what is enforced. Bringing in the historical Green Book and excerpts from James Loewen’s Sundown Towns also provide students with sometimes unexpected perspectives from which to consider the past.

In my classroom activity for exploring systematic and institutional racism, students read three excerpts from Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, watch Episode 3 of Race — the Power of An Illusion, and watch a 2018 PBS NewsHour clip about home ownership in Philadelphia. They also do their own research through internet searches to find statistics and infographics related to gentrification and loan access in the United States.

In the activity I with my students, after class discussions about unearned privilege and definitions of systemic or institutional racism, students brainstorm a list of observations of their own communities they think may be indicative of institutional racism. Students conduct a diversity census of their neighborhood and then search for data that would help answer the question, “Do we have equal opportunity for all races in the US?”

Students then read two Color of Law excerpts (p. 36-37, 64-65) for homework and watch portions of Race — the Power of An Illusion about redlining. In class, they analyz the statistics and graphs to determine what they tell us separately and collectively, what information is missing, what additional questions need to be asked, and what assumptions about race, class, and geography the data affirms or challenges.

After discussions of this material, students explore current estimates on net wealth, and list all the ways that “it takes money to make money” exists: school taxes and school quality, access to additional loans, etc. We then watch the PBS NewsHour clip to see another example of gentrification and students compared that story to their neighborhood census. Finally, they investigate local zoning and property tax laws.

I close the activity by assigning a third excerpt from The Color of Law, the Supreme Court challenges (p. 84-91), as we read or refer back to discussion of the role of the Supreme Court and three anti-canon cases woven into the course.

As a 6th grade class, we have been examining the idea of why people live where they live. I introduce Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law with the quote: “The core argument of this book is that African Americans were unconstitutionally denied the means and the right to integration in middle-class neighborhoods…”

We are a school in a suburb of Chicago, historically one of the most segregated cities in the country. In the lesson, we examined some of Rothstein’s research on redlining (albeit at a 6th grade level), mortgage inequality, and suburban white flight. We also integrated some discussion on modern social inequities such as the economic disparities within our own town (Villa Park): One school has a much higher rate of free and reduced lunch and is that correlated to demographics? Is that correlated to housing policy? Does that correspond to highway corridors connecting to the city (North Ave and Roosevelt Rd)?

As a comparison, I referenced Dr. Eve Ewing’s Ghosts in the Schoolyard which posits on the racism prevailing in Chicago politics over school closings after attending a speaking engagement to bring back information to share with the class.

As an assessment, students played the role of city planner and were tasked with mapping out an inclusive, integrated city complete with human and civil services and housing. They were to provide rationale for the location of their mapping encouraging them to think about not only who lives there but why.

My 8th grade class this year chose to investigate discrimination as part of an emergent curriculum rooted in students’ own questions and concerns. Towards the beginning of their investigations, they read an abridged version of “The Case for Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates. They prepared for and participated in a Socratic seminar on the reading. All students were interested in this essay and the stories shared in it, but some felt that it was unfair to ask people today to make reparation or amends for harms done by previous generations of Americans.

In a follow-up activity, I asked students to listen to Richard Rothstein discussing his book The Color of Law with the podcast hosts of “Have You Heard?” Students were by then in the early stages of production of a podcast of their own, so this was a good format for them to engage with the content, as they could use this podcast as a partial model for their own. We paused the audio periodically so that I could ask students what they understood about the role of the federal government and federal housing policy in people’s lives. How did federal policies give rise to housing segregation and housing discrimination? How did this limit Black Americans’ access to opportunities to build wealth and economic security? Why were the policies enacted? Who benefited? Who was harmed? How might the policies have had an impact on future generations?

After learning in more depth and detail about dejure segregation, students were much more likely to agree that our government today should play a role in repairing the harms of segregation and discrimination. For some, their concern shifted from the unfairness of white Americans being “punished” for actions of previous generations over which they had no control, to the unfairness visited on Black Americans who were legally barred from using their own resources to secure property and opportunity for themselves and their families.

I have actually used a variation on this lesson across all class levels, from Honors to Standard. It’s even come up in my Humanities and Sociology electives. For the US History classes, I primarily build the lesson around White Flight history in post-war America, where we examine redlining maps and FHA policies in the 1940s and 1950s. Depending on the level, students will do a close reading of some articles related to Rothstein’s book The Color of Law, and discuss whether they think this qualifies as de jure or de facto discrimination and why. The big reveal however, is when we compare the housing segregation problems of the mid-20th century to today, using the Racial Dot Map. When students see the continuing realities of segregation in current US cities and towns, they are completely floored. I’ve even had students research their own college demographics compared to this data to discuss diversity and affirmative action policies.

There’s also a C-SPAN lesson plan available on their educator website that includes some short clips of a book talk between Richard Rothstein and Ta-Nehisi Coates about The Color of Law. The clips are short enough to use with a variety of students at different learning levels. It allows students to not only read portions of the book, but hear Rothstein’s emphasis on what he determined to be the most consequential policies in shaping segregated housing in America.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn