“You can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail the revolution.” —Fred Hampton, a leader of Chicago’s Black Panther Party who was killed during an FBI-sponsored police raid.

Student-selected and student-run current events discussions are a daily ingredient of my high school social studies classes. The first 20 minutes of every 90-minute class period, we read an excerpt from a recent newspaper article and discuss its significance. In the last few years, the discussions have been dominated by names that have piled up with sickening frequency: Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland. My students, mostly Asian American and white, live in Lake Oswego, one of the wealthiest cities in Oregon and a community that benefits from mostly positive relationships with police. They struggle to understand a society that continues to allow Black lives to die at the hands of law enforcement.

This year, student attention has turned to how activists are responding to the racism in the criminal justice system, particularly the Black Lives Matter movement. In November 2015, a student brought in an Oregonian article, “Black Lives Matter: Oregon Justice Department Searched Social Media Hashtags.” The article detailed the department’s digital surveillance of people solely on the basis of their use of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag. My students thoughtfully discussed and debated whether tying #BlackLivesMatter to potential threats to police (the premise of the surveillance program) was justifiable, with most students agreeing with the Urban League and the American Civil Liberties Union that the U.S. Department of Justice acted improperly and potentially unlawfully.

But what was not noted in the Oregonian article was the historical resonance of this story, which recalls the ugly, often illegal, treatment of Black activists by the U.S. justice system during an earlier era of our history.

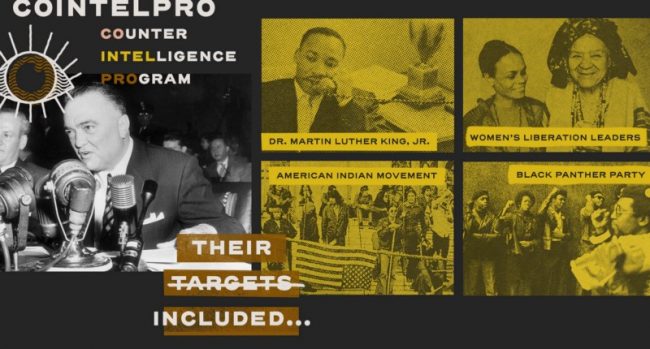

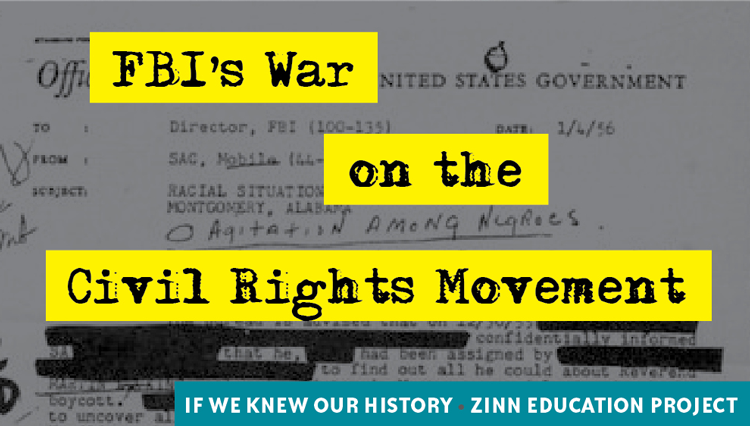

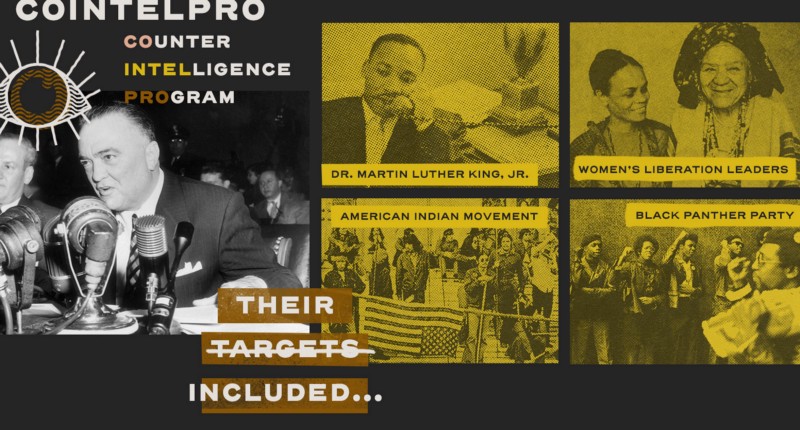

My students had little way of knowing about this story behind the story because mainstream textbooks almost entirely ignore COINTELPRO, the FBI’s counterintelligence program of the 1960s and ’70s that targeted a wide range of activists, including the Black freedom movement.

COINTELPRO offers me, as a teacher of classes on government, a treasure trove of opportunities to illustrate key concepts, including the rule of law, civil liberties, social protest, and due process, yet it is completely absent from my school’s government book, Magruder’s American Government (Pearson).

Classroom Stories

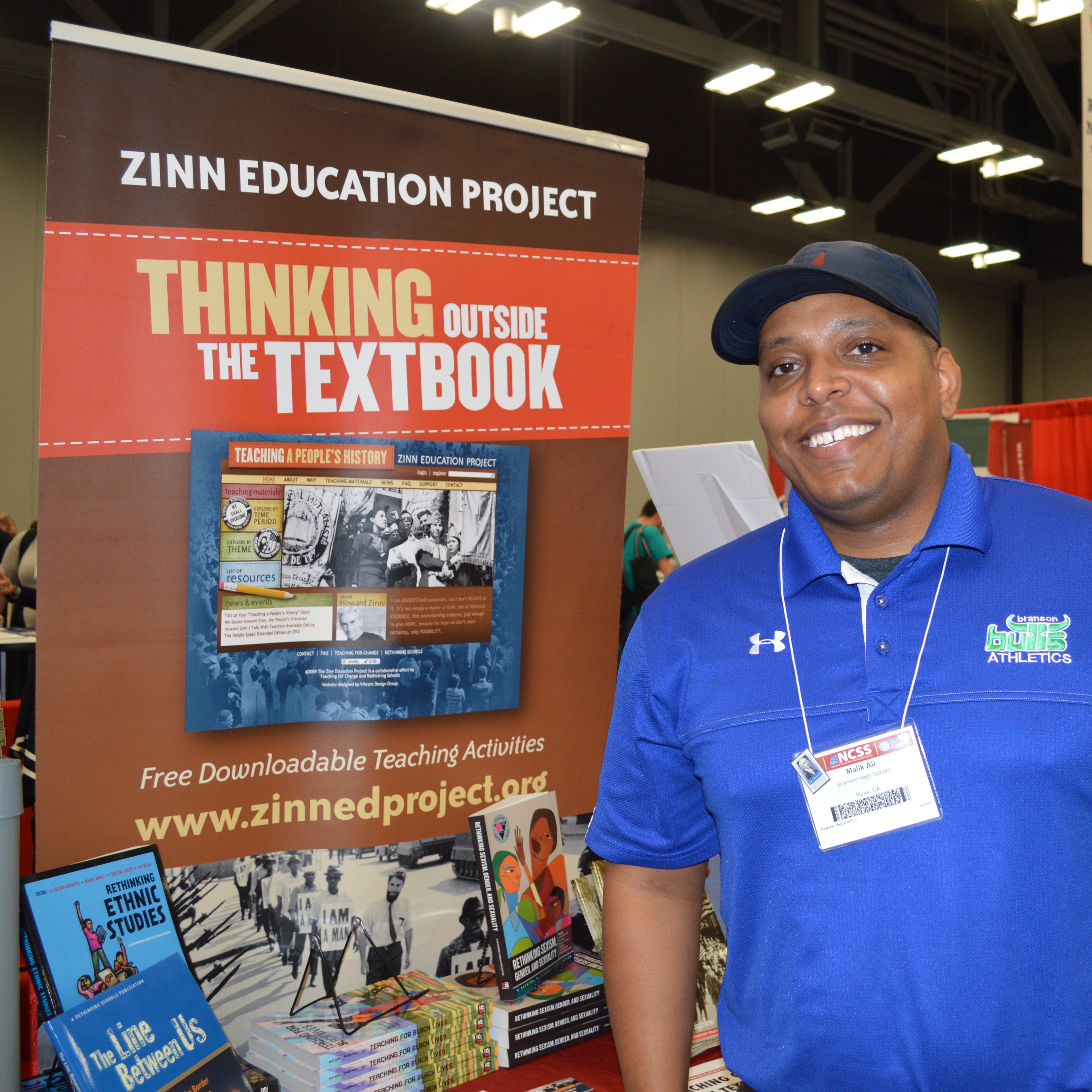

The Zinn Education Project’s COINTELPRO lesson plan made for a remarkable class session. I used the lesson as a capstone to a Civil Rights/Black Power unit.

While the underlying background sometimes astounded students, it was being able to see the historical narrative grounded in primary source documentation — to see a story that might seem beyond belief for some of them — that really inspired them to pay closer attention to their work.

They dug into and debated every paragraph of every document! It was an energy boost, new fuel for their thinking and communicating, for the remainder of the semester.

I executed the COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement activity with my 9th grade U.S. History students. They were engaged and enraged; curious and collaborative; eager to learn more and hungry for justice.

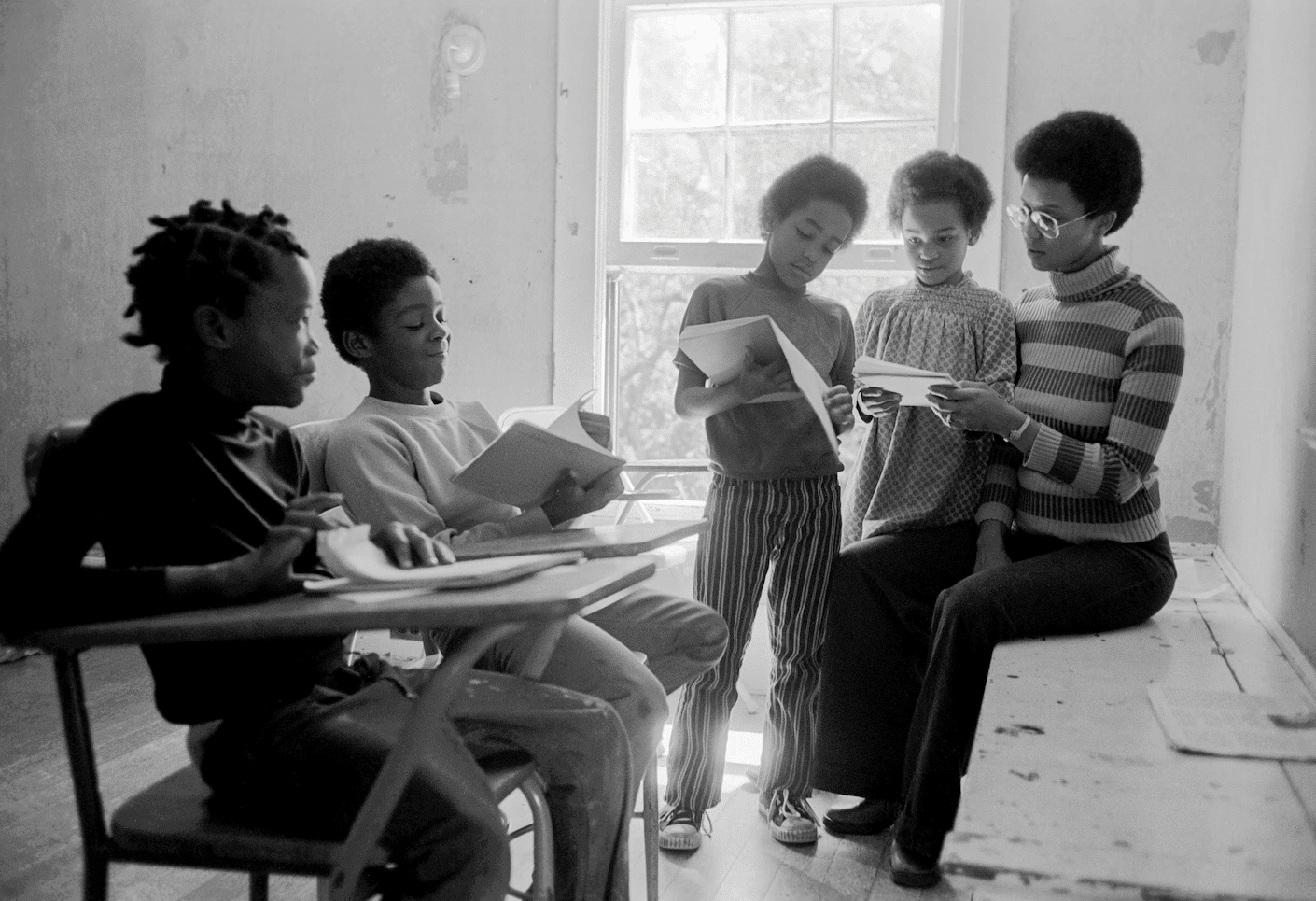

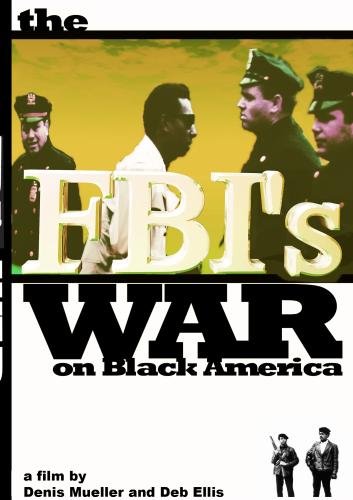

To activate their interest, I spent the first class period showing the Freedom Archives’ COINTELPRO 101 documentary. The documentary starts by exposing the COINTELPRO operations that successfully infiltrated the Puerto Rican independence, Mexicana, and Native American liberation movements and led to the incarceration and death of many activists. Since I teach a majority Latinx student population, they were immediately hooked.

The next day, we dove into the document analysis activity compiled by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. After going over key terms and background information (as suggested by Wolfe-Rocca in the PDF version of the activity), I arranged my students in groups of four and they investigated six of the included documents. For the full 90-minute block period students discussed, jotted down notes, and exclaimed in both horror and shock as they learned about a sliver of our country’s hidden history.

Unsurprisingly, many students were able to connect COINTELPRO to present day. Several of them bravely brought their own familial and personal experiences into class discussion. They shared stories of wolves in sheep’s clothing, covered by titles of police officer, government official, social worker, friend, or teacher, who had in some way or another sabotaged their family’s safety or livelihood. Per Wolfe-Rocca’s suggestion, we ended the class period as a group and candidly discussed both the risks of resistance and the importance of it.

Paradoxically, teaching people’s history leaves more room for hope than any other educational framework. When students are given permission to explore the whole truth without frills, we can discuss solutions in the form of direct nonviolent action and civil disobedience that actually mean something in the real world.

I teach U.S. history with students who have struggled in traditional classrooms. Because my students learn best through activities, role plays, and experiential learning, I’ve found the resources at the Zinn Education Project to be incredibly helpful in guiding students in engaging with historical narratives and perspectives.

Last spring we looked at the lessons from COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement, and my students got very into it. We did a gallery walk of leaked documents about the Black Panthers and the Civil Rights Movement, and even though my students often struggle with reading and document comprehension, the whole class was engaged with decoding what the documents were saying and what they could tell us about the FBI’s surveillance activities. After the class, they could still clearly identify the motivations and methods used in those documents and continued to bring them up throughout the rest of the year.

At the end of the year, when students were reflecting on the 20th century, several brought up this unit in particular as helping to cement their understanding of the challenges the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panthers faced and how activists could push back. I could really see how their understanding had developed thanks to this unit and others like it!

My students and I were especially intrigued by the COINTELPRO lesson, which is about the FBI targeting the Black Freedom Movement. In my own education, I was not taught this.

Oftentimes, textbooks teach the Civil Rights Movement as a moment when African Americans stood up for their rights and were granted them under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, it does not include the African American struggle in the post-civil rights era.

I believe, as educators, it is our ethical duty to expose students to the truth of American history and the Zinn Education Project helps me do just that!

I absolutely love the COINTELPRO lesson which has students look closely at the actual documents leaked to the press detailing the operation. As a class, we have been studying the story of Fred Hampton and his murder. We have looked closely at how powerful Hampton became through class solidarity and the revolutionary politics that brought the Rainbow Coalition together. We also discussed how this made him a real threat to the ruling class and the status quo, resulting in his murder by the FBI.

The lesson on COINTELPRO electrified my students. They could not believe they were looking at the actual documents which we had learned so much about. Further, we were in the process of viewing Judas and the Black Messiah. Late in the movie, when William O’Neal is pressured by the FBI to draw a floor plan of Hampton’s apartment, students immediately pointed out that we had looked at this actual floor plan as a class in our previous lesson.

Student engagement and excitement skyrockets when they see learning as authentic and applicable to today. This lesson helped provide both and more.

This site is an essential tool when trying to untangle the complex history of race in America.

No matter what, the lessons that seem to shock my students the most center on the Black Panther Party and COINTELPRO. Even though I’m providing the materials to students, they still come up to me aghast and say, “Did you know about this?” The demonization still present when speaking about the Black Panther Party in this country is astounding. Even students who grew up in predominately Black communities have only learned about the Black freedom movement as one of violence and hatred. When they learn of the murder of Fred Hampton, there is nearly palpable anger.

The last time I taught with these materials, I had a student who almost never did his work. He was trying to graduate and had to do one final project and chose this time period. When he realized no one had taught him this history in his 12 years of school, he was astounded. He put in more effort on that project than any of the 60 other students with similar projects. The idea that he had been manipulated and taught to hate people who were trying to help their own community resonated as a reflection of what is happening with the Black Lives Matter movement and the classification of that group as a hate group.

As a teacher of African American history, my class generally centers on how the shaping of narratives changes the way that history is interpreted. Students come to my class used to talking about slavery and Black struggle, but also having a limited understanding of the overall scope of the African American experience. They presume history goes like this: Slavery was bad, then it ended, things got a little better but not enough, so MLK came along and everything was good, until some people turned their back on his peaceful mission and ruined it for everyone. This is the traditional narrative that I get when I ask students to write out what they know about Black history.

Once we start to delve into the stories, the students start to see how much manipulation is built into the U.S. education system.

I was incredibly impressed with the materials presented during a workshop on the Civil Rights Movement and a COINTELPRO lesson by the Zinn Education Project during the NCSS conference in 2018. Since then, I have used facets of that specific lesson, such as the sources on the Black Panthers, in class to spark discussions with my students.

I was so happy I discovered both the Zinn Education Project and this lesson, in particular. It provides a different lens that I had not previously given to my class, regarding the Black Panthers. The lesson as a whole allows for links to current events and issues in today’s society as well.

This lesson was originally published in the Spring 2016 issue of Rethinking Schools magazine.

It is included in the Rethinking Schools publication Teaching for Black Lives.

Find related teaching resources below. In addition, find graphic art about COINTELPRO by illustrator Stacey Uy by clicking the image above.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn