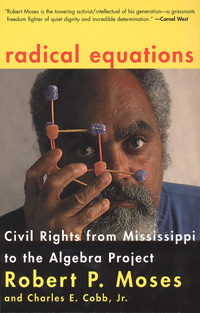

This is a talk delivered by SNCC veteran Charles E. Cobb Jr. on Sunday, January 15, 2017, at the People’s Congregational Church in Washington, D.C. on the occasion of the Dr. Martin Luther King holiday.

By Charles E. Cobb

My friend and former co-worker in the movement Julian Bond, who is greatly missed, used to say that the primary misconception in the public’s perception of the Southern Civil Rights Movement can be boiled down to three short sentences.

Rosa sat down. Martin stood up. And then the white folks saw the light and saved the day.

In the minds of many, the movement is thought of as mass protest in public spaces led by charismatic leaders. That is only partly true, however. The organizing tradition — a very old tradition, with roots in slave rebellions — better describes the movement. And, I want to push this forward as what is most relevant for continuing struggle in the 21st century as well as properly understanding movement history. And that does not mean that mass protest — those of yesteryear and those now, contradicts this tradition.

My approach to discussing the movement this morning is from the bottom up, or put another way, from the inside out since I was very much involved with the movement as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC. We were an organization of grassroots organizers.

First, as much as the movement challenged segregation, racial discrimination and white supremacy, fundamental to real understanding of the movement are the challenges Black people made to one another within the Black community. This underappreciated dimension of the movement is as important today as it was more than half a century ago. Maybe even more important now, given the kind of violence we are witnessing in Chicago and other cities.

Martin Luther King, Pete Seeger, Rosa Parks, Ralph Abernathy, and Charis Horton at Highlander Institute in 1957.

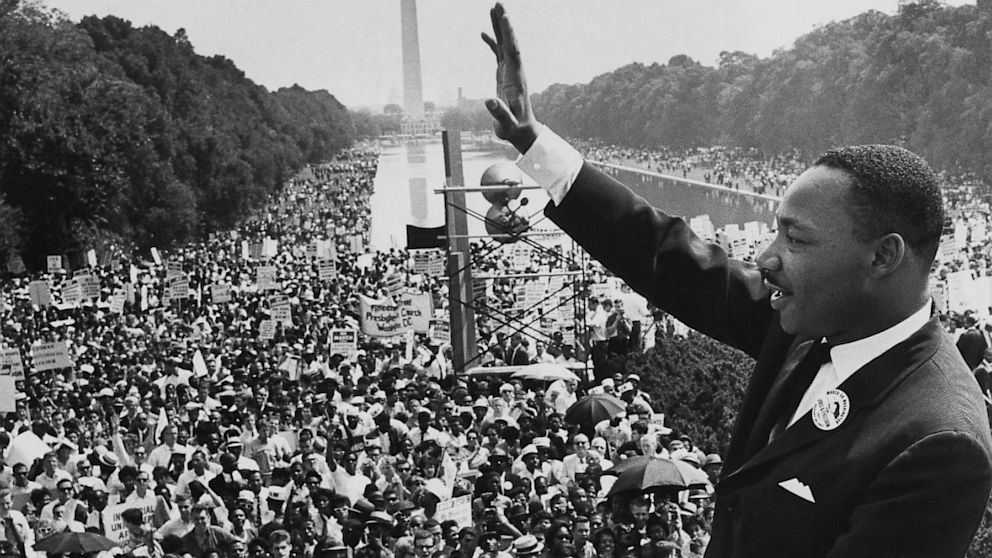

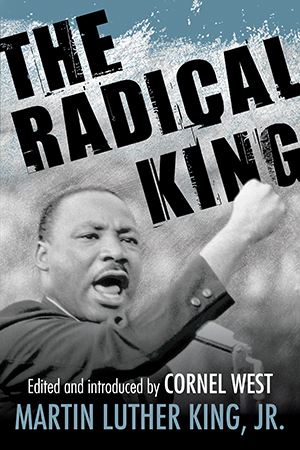

Martin Luther King was born today in 1929; we are celebrating his work. So before going further, let me tell you a story about Reverend King that is relevant to the point I have just made.

Few people give enough thought to the fact that before he achieved national and international renown as a civil rights leader, Martin Luther King was a young local minister in Montgomery, Alabama. How he emerged is important to understanding the emergence of the bus boycott there, which was driven by local people at the grassroots.

After Rosa Parks‘s arrest, Black Montgomery organized a highly successful one-day bus boycott. I am tempted here to discuss Mrs. Parks at length. She was much more than a weary dressmaker seeking a place to sit on the bus. As she put it, her life was “a history of being rebellious.”

At the end of the day, Montgomery’s Black leadership — many of them ministers — met in Martin Luther King’s church to discuss continuing the boycott until the city committed to desegregation of bus seating. Most who spoke, expressed various degrees of reluctance and fear about doing this. Finally, the preeminent Black leader of Montgomery — E.D. Nixon, one of A. Philip Randolph’s union men and the former head of Alabama’s NAACP — rose and spoke.

As the story came to me from Johnnie Carr, 95-years-old when she was telling it, and part of a core group of women who had been working with Rosa Parks since the 1940s, Nixon basically accused the gathering of cowardice: “You preachers been eating these women’s fried chicken long enough without doing anything for them.” It was women, after all, riding buses across town into the white community to jobs as housekeepers and cooks and nursemaids who suffered regular humiliation traveling on public transportation. “Now,” Mr. Nixon continued, “it’s time to get up off your butts and do something for them!”

It was then that a 26-year-old Martin Luther King stood up. Do we even think of Martin Luther King as a 26-year-old? “I am not a coward!” He said. The embarrassed gathering agreed to continue the boycott and Reverend King was elected head of the organization they formed at that meeting to continue the boycott — The Montgomery Improvement Association.

The way to understand this moment, I hope you see, is by understanding the kind of challenges Black people were making to one another across the South. This is what drove struggle and change. Much of this still remains invisible. And broadening this with an almost equally invisible related point: The Movement thrust forward leaders, not the other way around.

However, as important as he was, I am not here this morning to discuss Martin Luther King. I intend to concentrate instead on Mississippi and its lessons, particularly as they apply to these times. That is the state where I worked as a SNCC field secretary from 1962 until 1967, and the state I know the best.

The vicious racial oppression that once so completely defined this state establishes a special kind of clarity for us this morning. To illustrate this, in a moment I will read to you a description of an encounter reported by another friend, and comrade, and hero from the days of Mississippi’s mid-20th century freedom struggle. Sam Block is his name. He, like almost everyone who formed the backbone of the Southern movement, is invisible and he died far too young from both the physical and psychological traumas of that struggle.

Rally for the Freedom Vote, Hinds County, 1963. Front row, L-R: NAACP leader Aaron Henry, SNCC organizers Sam Block and Willie Peacock. Back row: Rev. Ed King with bandage on face. Image: crmvet.org

The words will come from a 1962 field report Sam wrote describing the early days of his efforts to organize around voter registration in the Mississippi Delta. Sam was the first of us — meaning the first of us who were young — 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, and 23-years-old — to organize for voting rights in the Mississippi Delta — cotton plantation country. The Delta was a vicious place where most Black life had been reduced to plantation serfdom following the dismemberment of Reconstruction. The Delta was where the White Citizens Council was born. Sam began working in a town where the White Citizens Council was particularly powerful — Greenwood — county seat of Leflore County. Greenwood and the rest of the county, like most other Delta towns and counties, was two-thirds Black. When Sam arrived, there were more than 13,000 voting-age Blacks in Leflore County, but only about 200 had succeeded in being registered. Listen to Sam’s report. The N-word, as we now say in polite company, is used in it; but it is necessary, I think. However, I apologize in advance for any discomfort its use causes. Here’s Sam words:

We went up to register and it was the first time visiting the courthouse in Greenwood, Mississippi, and the sheriff came up to me and he asked me, he said, “Nigger where you from?” I told him, “Well I’m a native Mississippian.” He said, “Yeh, yeh, I know that, but where you from? I don’t know where you from.” I said, “Well, around some counties.” He said, “Well I know that, I know you ain’t from here ’cause I know every nigger and his mammy.” I said, “You know all the niggers, do you know any colored people?” He got angry. He spat in my face and he walked away. So he came back and turned around and told me, “I don’t want to see you in town any more. The best thing you better do is pack your clothes and get out and don’t never come back no more.” I said, “Well, sheriff, if you don’t want to see me here, I think the best thing for you to do is pack your clothes and leave, get out of town, ’cause I’m here to stay; I came here to do a job and this is my intention. I’m going to do this job. . .

Now I think this exchange, which took place on the steps of the Leflore County courthouse, explains everything you need to know about the movement. Sam’s words were a promise and a prediction. Along with Sam, those of us in SNCC and CORE especially, dug in and stayed to do the job; were committed to doing the job, and drawing from deep wells of strength in Black communities, broke the back of apartheid in Mississippi. But the outcome did not just affect Mississippi; it changed America. The job we did resulted in changing forever the rules of the national Democratic Party and that is what laid the groundwork for the Obama presidency. This is not boast, but history. Basically: In fighting for the right to vote—and winning—the door was opened to the possibility of winning any elected office, even the highest in the land. As the Black abolitionist Fredrick Douglass pointed out more than 150 years ago and it’s as relevant now as then, “If there is no struggle there is no progress.” I stand here in praise of our struggle, and to testify that the violence underlying the Greenwood sheriff’s words reveal the blood-soaked ground in Mississippi and across the American South that has been the price of progress. I stand here to insist that this must never be forgotten, and that there is a debt, a duty — an obligation we have — all of us — to repay this history with continuing struggle.

Approaching this history, there are, of course, some legitimate questions you may want answered in trying to grasp why I think Sam’s courthouse encounter with the sheriff was so significant. Who was Sam Block? He was only 22 when this happened; that’s kind of young, isn’t it? How did he get to Greenwood? What made him stay in defiance of the sheriff’s threat? The larger question is: Is there something we can use here today?

So, let’s look more closely at Sam. Youth comes immediately to mind in this consideration. As I said, he was just 22-years-old at the time of his confrontation with the sheriff. Largely missing from the narrative about the Civil Rights Movement is that in many instances it was led by young people like Sam. To quote Martin Luther King speaking in support of sit-ins at a February 16, 1960, civil rights rally in Durham, North Carolina: “What is new in your fight is the fact that it was initiated, fed, and sustained by students.”

I was a 12th grade high school student when on February 1, 1960, the sit-in movement erupted in Greensboro, North Carolina. Black students there began refusing to leave whites-only lunch counters and restaurants. Within two months such protests had spread to 80 southern cities. The student protests in Nashville, Tennessee, Atlanta, Georgia, and other Southern cities that year, reached us via television and newspapers — especially Black newspapers. And for me and most of my friends, before seeing these sit-ins, civil rights had been something grown-ups did. Now, looking at young people like Diane Nash or John Lewis or Julian Bond — students, my generation — what was coming through to us was that civil rights struggle was something we could do.

We see something similar in the way that protests over the 2012 murder of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, have led to an ever-expanding Movement for Black Lives that is led by young people. A whole new set of young leaders has begun to emerge and lay claim to the future they want to live in; launched a fight for their future. As a SNCC veteran, I see a lot of my younger self in this, and applaud it.

Sam was also one of Amzie Moore’s people. That’s who sent him, via SNCC to Greenwood. SNCC, which grew out of the sit-in movement had by 1962 evolved into an organization of organizers, working closely and at the grassroots with older veterans of civil rights struggle — many of them local NAACP leaders like Amzie. You won’t know his name any more than you knew Sam’s, but you need to know some things about Amzie because understanding what he represents is another essential component of any real discussion about the movement.

Amzie Moore was the president of the Cleveland, Mississippi NAACP where Sam had been born and grew up, and had decided that he wanted to tap into and use the young energy he saw in the sit-in students. He admired what the students were doing, but was not interested in organizing sit-ins in his town; he wanted a voter registration campaign. He put that idea on our political plate, challenging our idea that “direct action” only meant sit-ins and picket lines of protest. Amize wanted to see the emergence of Black power in the Delta. The Black people were there; the registered Black voters were not.

As we began working in the Delta, Amzie Moore’s home was our central headquarters. His house was an orientation center, a place for breakfast of scrambled eggs or for a spaghetti dinner; it provided telephone connections and was always full of conversation as well as Amzie’s sometimes grim, sometimes funny stories of Delta life and earlier civil rights struggle. Floodlights washed his backyard because he was certain that one night Ku Klux Klansmen, or white terrorists of some sort, would attack his home. Often Amzie, who had fought the Nazis overseas after all, sat in the bay window of his living room with rifles and pistols, waiting to repel an attack he was certain would come (which may be why it never came).

Our relationship with Amzie puts into perspective yet another important dimension of the movement: The convergence of young people — like Sam. . . or myself — with older people like Amzie — he was 49-years-old when we met him. I had just turned 19 in 1962. They were willing to share their experiences and open up to us, networks that they had built over many years, even decades, of struggle.

Ella Baker (center) at the Highlander Center.

Ella Baker introduced us to Amzie. She was 59-years-old. You cannot talk of 20th century civil rights struggle without discussing this remarkable woman. And let me also say as an aside here, although it should really be central to any discussion, that you cannot talk about 20th century civil rights struggle without discussing the leadership of women. Ms. Baker was the NAACP’s Director of Southern Branches in the 1940s, was the person who organized Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) after the 1955-56 Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott. She immediately recognized the significance and potential of the emerging student sit-in movement in 1960 and negotiated $800 from Reverend King to bring student protest leaders together at her alma mater, Shaw College in Raleigh, North Carolina. Out of this meeting came SNCC. As much as anyone, and more than most, her hands and her brains shaped the theory and methods of community organizing which defines the modern Civil Rights Movement. Her main lesson: Organize from the bottom up. “Strong people don’t need strong leaders.”

Although a number of historical forces mark the era of modern civil rights struggle, in my opinion, the convergence of some very particular and very critical forces laid the foundation for the modern mid-20th century struggle from which there would be no turning back: the commitment to democracy and human rights embedded in the rhetoric of World War Two’s fight against fascism, the accelerating struggles for decolonization in Africa and Asia, post war economic and educational opportunity in the United States with so much of the world in rubble, and finally: the 1954 supreme court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that began the process of dismantling the legal framework which underwrote U.S. apartheid. Importantly, that decision engendered hope, one of the indispensable ingredients for resistance.

What uniquely marks the era, though, is that in large numbers, people who were usually spoken for by others, began to speak for themselves; and not only that, spoke for themselves in such a way that they could not be ignored. This is very important so let me restate it in a slightly different way: Ordinary people who were usually spoken for by sympathetic advocates, or of, by hostile white supremacists, began speaking for themselves saying, “This is what we demand; this is the kind of society in which we wish to live.” Montgomery, Alabama’s mid-1950s bus boycott and the now almost completely forgotten student struggle in 1951 Farmville, Virginia, may be the post-World War II events that best represent this. I also think the person who probably best symbolizes this is Fannie Lou Hamer of Mississippi. She was a sharecropper and timekeeper on a Delta cotton plantation who became not only a leader of Mississippi’s 1960s movement, but a great national voice for civil rights. In any case, maids, sharecroppers, day workers, cooks, janitors, farmers, factory workers, beauticians and barbers, as I said, ordinary people who were usually spoken for or of — these voices began to be heard, or at least could no longer be ignored in the mid 20th century. And, through organization and direct action they changed a way of life.

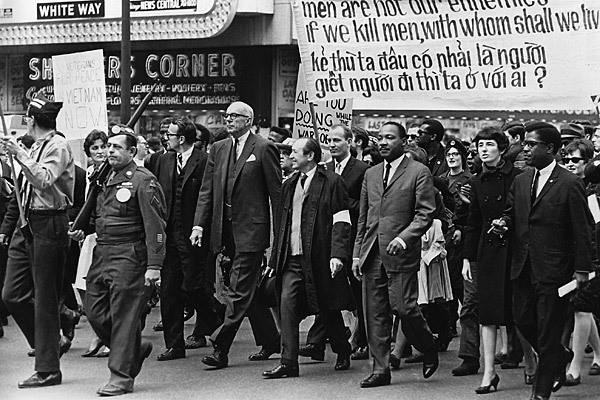

It is worth noting as we seem to have entered an era where civil liberties are being eroded in the name of national security that the Civil Rights Movement forced the issue of civil liberties. In 1963 Bernard Lafayette, one of the leaders of the Nashville Student Movement organized the first civil rights mass meeting in Selma, Alabama. When Sheriff Jim Clark burst in with his deputies and disrupted the meeting he was armed with a warrant from the circuit judge empowering him to prevent “insurrection.” And in the months leading up to the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project approached, the state legislature passed a “criminal syndicalism” law. It empowered local authorities to redefine organized civil rights struggle (or labor union organizing) as “terrorism” with 10 years of imprisonment possible for any person who “by word of mouth or written words or personal conduct advocates, instigates, suggests, teaches, or aids and abets criminal syndicalism or the duty, necessity, propriety, or expediency of committing crime, criminal syndicalism, sabotage, violence, or any other unlawful method of terrorism as a means of accomplishing or effecting a change in agricultural or industrial ownership or control or effecting any political or social change. . .” Whew! After the first group of people tried to register to vote in Sunflower County, Mississippi, white nightriders shot up the Black community. In Ruleville, a tiny Delta town, two girls were wounded. I was arrested for the shooting, by the mayor, who said I had done it to gain publicity for a failing movement. I was let go the next morning. If also charged and convicted as a criminal syndicalist, I could have had 10 years in jail added to whatever sentence I was given for the shooting.

Looking across today’s political landscape I cannot say that such oppressive legislation is no longer possible. Fear often leads to tyranny.

In the United States today, with civil rights and civil liberties so vulnerable, the most important lesson of the Civil Rights Movement is still relevant. You have to make a demand for the kind of society in which you want to live — especially if you want to live in a free society. As we used to say, “Freedom is not free.”

And this brings us to the Movement for Black Lives today. Alicia Garza, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter wrote a year or so ago, “When we say Black Lives Matter, we are talking about the ways in which Black people are deprived of our basic human rights and dignity. It is an acknowledgement [that] Black poverty and genocide is state violence. It is an acknowledgment that 1 million Black people are locked in cages in this country — one half of all people in prisons or jails — is an act of state violence. It is an acknowledgment that Black women continue to bear the burden of a relentless assault on our children and our families and that assault is an act of state violence.” Ms. Garza’s framing mirrors the concerns with systemic oppression that we held while fighting for change in the South.

I, for one, think their protests have been powerful and effective. Now they face the question of organizing beyond protest, a question we had to face too. A question we also have to face is how to support this young movement. We might begin by talking to them seriously about their ideas. I believe the earlier movement history I have offered here can be of some use to the young people working to maintain our ongoing struggle today. Obviously, while not everything from our era will be useful for 21st century activists, there is a core reality that strong movements are built by developing inclusive relationships capable of knitting together strategies formed as a result of listening to ordinary people’s experiences and ideas for change. More than any single thing this is what the movement did in order to engage in effective struggle. I think doing this in the Black urban communities that now form the heart of Black America is much more difficult than what we were faced with in the rural south of the 1960s, but the basic principle of digging in and finding a language that works remains fundamental. This is a conversation we do not have time for this morning. But I do know that this discussion has begun among some of the groups that form the Movement for Black Lives. So, as the Mozambicans used to say in their struggle for independence from Portugal — a Luta Continua, the struggle continues.

Finally, I ask you to consider this which can serve as a theme for today’s struggle as much as it served as the founding principles of the United States in 1787:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

For all the contradictions found throughout U.S. history this is the core, though still unrealized, ideal of the country. But do we really want to do this? Government as we’ve known it since the country’s inception has always been ambivalent, and at many times, hostile to this ideal. And this idea is really the heart of my message to you this morning; what we learn in the passage of time from Martin Luther King’s emergence to the now of Black Lives Matter. It’s the emergence of ordinary people as leaders and spokespeople who are the real force for change — people who keep their eyes on the prize, as the old song goes. And today, this need is more urgent than it has ever been. And perhaps, too, more possible. I am, in effect, challenging each one of you to be the change. A luta continua.

Charles Cobb and SNCC veteran Philippa Jackson, who introduced Cobb at the church service.

Thank you.

Charlie Cobb

Peoples Congregational Church

Washington, D.C.

January 15, 2017

Charles E. Cobb Jr. is a former field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a journalist, and the author of a number of books including This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (Basic Books, 2014). Read more.

Cobb opened his talk at the church with these acknowledgements:

My thanks to Reverend Hopson, the congregation of Peoples Church, and especially the church’s Board of Christian Social Action for inviting me here. I grew up in the Congregational church. My father, Reverend Charles E. Cobb, pastored St. John’s Congregational Church in Springfield, Massachusetts, and later co-founded the UCC’s Commission for Racial Justice and became its first executive director. So I feel like I have come back home and welcome the opportunity to speak to you. Thank you.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn