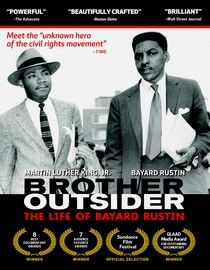

He was there at most of the important events of the Civil Rights Movement — but always in the background. Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin asks “Why?” It presents a vivid drama, intermingling the personal and the political, about one of the most enigmatic figures in 20th-century American history. One of the first “freedom riders,” an adviser to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and A. Philip Randolph, organizer of the march on Washington, intelligent, gregarious and charismatic, Bayard Rustin was denied his place in the limelight for one reason — he was gay.

He was there at most of the important events of the Civil Rights Movement — but always in the background. Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin asks “Why?” It presents a vivid drama, intermingling the personal and the political, about one of the most enigmatic figures in 20th-century American history. One of the first “freedom riders,” an adviser to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and A. Philip Randolph, organizer of the march on Washington, intelligent, gregarious and charismatic, Bayard Rustin was denied his place in the limelight for one reason — he was gay.

Rustin was born in 1912 into a Pennsylvania Quaker family steeped in ideas of social justice and non-violence. He moved to Harlem during the socially and culturally tumultuous 1930s and, after a brief flirtation with the Communist Party found a more congenial home in A.J. Muste’s pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation. While there, he served prison terms for resisting the draft during World War II and later for integrating interstate buses. When A. Philip Randolph, aging head of the Black labor movement, turned to the fellowship for tactical help, Rustin worked closely with him and developed a belief that the labor movement offered the best hope for Black advancement.

Then in 1953, Rustin was arrested during a casual homosexual encounter. A. J. Muste forced him out of the fellowship. When the Montgomery bus boycott was launched, he went to Alabama in 1956 and became a mentor in non-violence to the 26-year-old Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Though Rustin would advise the younger civil rights leader until his assassination in 1968, King broke publicly with Rustin in 1960, when Representative Adam Clayton Powell threatened King over the issue of Rustin’s homosexuality.

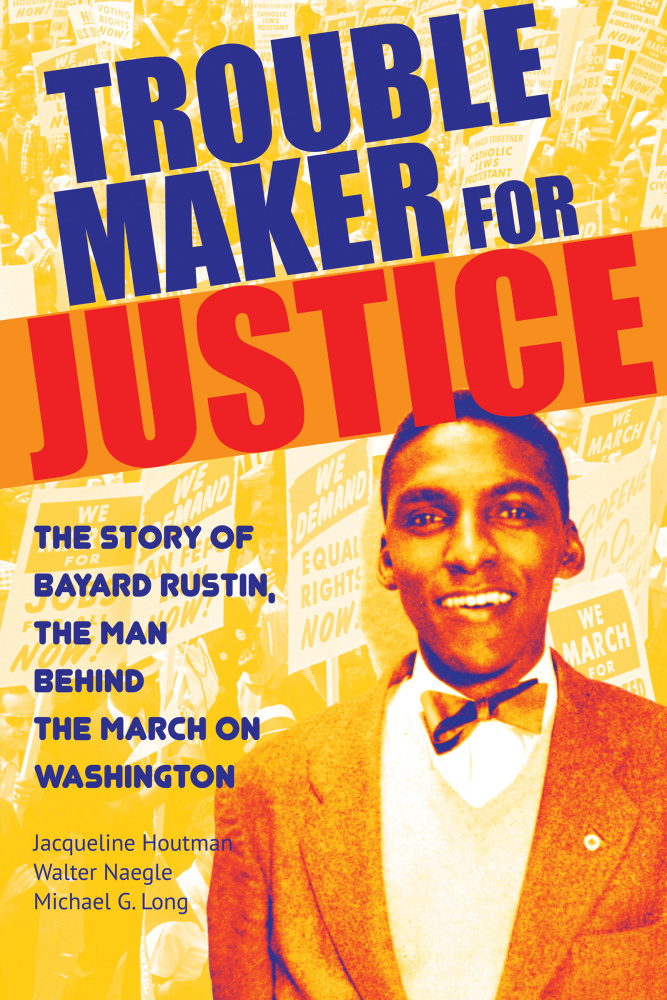

But when the 1963 march on Washington was proposed, the civil rights leadership recognized there was only one man who could organize it — Bayard Rustin. After the march’s overwhelming success Rustin forged the fragile alliance between the labor unions, the Civil Rights Movement and the Democratic Party which was responsible for much of the landmark civil rights legislation of the 1960’s.

But when the 1963 march on Washington was proposed, the civil rights leadership recognized there was only one man who could organize it — Bayard Rustin. After the march’s overwhelming success Rustin forged the fragile alliance between the labor unions, the Civil Rights Movement and the Democratic Party which was responsible for much of the landmark civil rights legislation of the 1960’s.

Later on, Rustin angered former colleagues by not speaking out against the war in Vietnam, and by taking controversial stands against Black Nationalism and affirmative action. In the 1970s and 1980s, he returned to his early interest in international affairs and human rights, working on behalf of refugees around the world. [Producer’s description.]

Produced in associated with the Independent Television Service (ITVS).

Trailer

Find more resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn