The 1912 Bread and Roses Strike in Lawrence, Mass., was one of the most significant struggles in U.S. labor history due to its level of organization and collaboration across ethnic and gender lines. Thousands of largely female workers engaged in a lengthy, well-organized, and successful walkout, standing firm against an entrenched group of mill owners and their hundreds of militia and police. Workers maintained soup kitchens and nurseries for children. Meetings were simultaneously translated into nearly 30 languages. Representatives from every nationality formed a 50-person strike leadership group.

Despite this incredible organization, the pivotal 1912 Bread and Roses Strike is not mentioned at all in 10 out of 12 major U.S. history textbooks in a 2011 survey conducted by the Zinn Education Project. The two books that reference the strike describe it as “erupting . . . in the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts” (A People and a Nation, Houghton Mifflin) and “Workers spontaneously went on strike” (Give Me Liberty!, Norton). The image of workers spontaneously saying “enough is enough” is inspiring. But it is not true. Workers weren’t passive until the minute they could take no more. A deeper understanding of events leading up to the strike in Lawrence challenges this facile history.

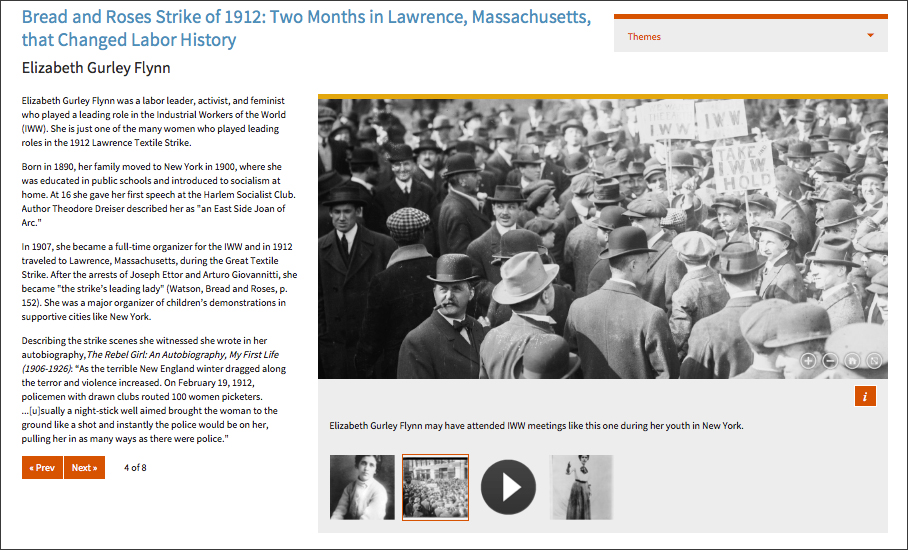

The trust and solidarity required to mount a successful strike was not magically born on January 11 and 12, 1912, when workers walked off the job due to a reduction in their pay. Some 20 active foreign-language chapters of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were present in the city for at least five years. IWW organizer James P. Thompson stated in the October 1912 issue of Solidarity: “It is absolutely foolish to say the strike ‘happened without any apparent cause’; ‘that it was lightning out of a clear sky,’ etc. As a matter of fact, it was a harvest, it was a result of seeds sown before. . . ”

The trust and solidarity required to mount a successful strike was not magically born on January 11 and 12, 1912, when workers walked off the job due to a reduction in their pay. Some 20 active foreign-language chapters of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were present in the city for at least five years. IWW organizer James P. Thompson stated in the October 1912 issue of Solidarity: “It is absolutely foolish to say the strike ‘happened without any apparent cause’; ‘that it was lightning out of a clear sky,’ etc. As a matter of fact, it was a harvest, it was a result of seeds sown before. . . ”

Along with the IWW, the Italian Socialist Federation (ISF) played a significant role in the strike. ISF members, among the first workers out of the mills, provided local leadership and strategies to the larger strike force. They had strong ties to radical labor organizations throughout Italy and other European countries.

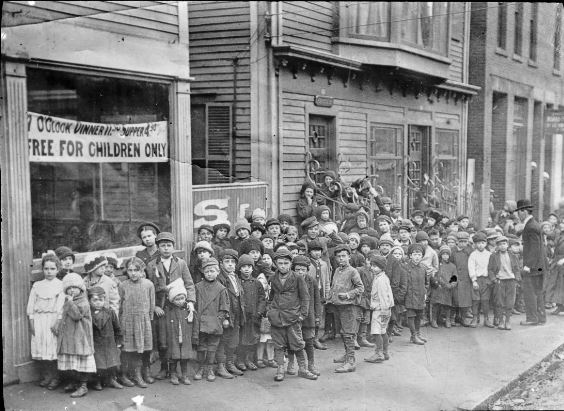

Organization also grew out of the experiences immigrant workers brought with them to Lawrence. Franco-Belgians established a cooperative modeled after institutions in France and Belgium, in 1905. The cooperative operated its own bakery as well as its own grocery store and meeting hall. As Franco-Belgian immigrant August Detollenaere noted, “The union is the place of combat; the cooperative must be . . . a financial and moral support.” He and many other Lawrence workers carried their labor histories with them into the city’s mills and drew on their experiences to build vital worker organizations across the city.

During the strike, the Franco-Belgian soup kitchen fed workers’ children. Image: Digital Public Library of America. (Click image to see more.)

Workers had walked off the job before 1912 and drew on these experiences. In 1910, a newly organized weavers union used the Franco-Belgian hall as its meeting place, as did a group of 87 women who walked out of the Ayer Mill in 1911 to obtain a pay increase. Franco-Belgian workers also organized textile workers in other New England cities.

The Lawrence Eagle Tribune reported on a strike meeting held on Friday, January 11. “Voting unanimously to walk out if their pay for 54 hours is less than that received for 56 hours, several hundred Italians, Poles, and Lithuanians, who are employed in the local mills, met last evening at Ford’s Hall. A majority of those who attended the meeting will receive their pay today. A mass meeting will be held Saturday afternoon at 2 o’clock in the City Hall at which speakers in English, Italian, Polish, and French will be present.”

The Syrian Independent Drum Corps was one of many marching bands that played before meetings and in the streets. Photo from Eagle Tribune.

Reporters discerned the level of organization in the city. From the February 10, 1912, issue of The Outlook: “There are almost as many nationalities here in Lawrence as there are in your Babel of New York. The workers are American, English, Scotch, Irish, German, French, Flemish, French-Canadian, Polish, Italian, Syrian, Russian, Armenian. I heard speeches in six languages. You might not suspect that a common sentiment could animate these diverse groups and weld them into a fighting unit. Nevertheless they have struck-struck as a single homogenous body.”

Female networks in Lawrence’s ethnic neighborhoods also added strength to the strike. Workers, wives, and mothers forged strong alliances with neighbors in their tenement blocks. Such networks contributed to the solidarity essential to sustaining the strike of 1912. (Learn more in Radicals of the Worst Sort: Laboring Women in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1860-1912 by Ardis Cameron.)

Mill laborers, their families, and their neighbors stood up against the city’s entrenched mill aristocracy and the police and militia determined to break their strike. A lesser organized strike might well have collapsed. Instead, thousands of workers joined singing picket lines that snaked for blocks through the city’s commercial and mill districts.

To suggest that the 1912 strike started in a flash over a wage cut diminishes the purposeful behavior of hundreds of immigrant laborers who built unity out of diversity. It also diminishes the importance of organized labor today and organized efforts to challenge injustices from climate change to the criminal justice system. If students learn the textbook lessons about the Bread and Roses Strike, they’ll be led to believe that we just need to wait for the next spontaneous reaction to injustice. It’s time to teach outside the textbook about the real history of the Bread and Roses Strike.

Robert Forrant is a history professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell; chair of the Bread & Roses Centennial Committee; and co-author of Images of America: Lawrence and the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike and The Big Move: Immigrant Voices from a Mill City.

Robert Forrant is a history professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell; chair of the Bread & Roses Centennial Committee; and co-author of Images of America: Lawrence and the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike and The Big Move: Immigrant Voices from a Mill City.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn