On Monday April 1, 1967 “George Dowell and several neighbors from North Richmond, California . . . heard 10 gunshots. Sometime after 5:00 a.m., George came upon his older brother Denzil Dowell lying in the street, shot in the back and head. Police from the county sheriff’s department were there, but no ambulance had been called. . . . [The] sheriff’s office reported that deputy sheriffs Mel Brunkhorst and Kenneth Gibson had arrived at the scene at 4:50 a.m. on a tip from an unidentified caller about a burglary in progress. They claimed that when they arrived,Denzil Dowell and another man ran from the back of a liquor store and refused to stop when ordered to halt. Brunkhorst fired one blast from a shotgun, striking Dowell and killing him. . . . “For the Dowells, the official explanation did not add up, and community members helped the family investigate. . . . There was no sign of entry, forced or otherwise, at Bill’s Liquors, the store that Dowell had allegedly been robbing. Further, the police had reported that Dowell had not only run but also jumped two fences to get away before being shot down. But Dowell had a bad hip, a limp, and the family claimed that he could not run, let alone jump fences. . . . A doctor who worked on the case told the family that judging from the way the bullets had entered Dowell’s body, Dowell had been shot with his hands raised. . . . Mrs. Dowell publicly announced, ‘I believe the police murdered my son.’ . . . A white jury took little time deciding that the killing of unarmed Dowell was ‘justifiable homicide’ because the police officers on the scene had suspected that he was in the act of committing a felony. Outraged, the Black community demanded justice.”

—Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr., Black Against Empire:

The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party

Helping North Richmond’s Black community demand justice for the killing of Denzil Dowell was one of the first major organizing campaigns of the Black Panther Party. The first issue of The Black Panther newspaper, which at its height around 1970 had a circulation of 140,000 copies per week, asked “Why Was Denzil Dowell Killed?” Anyone reading the story of Dowell today can’t help but draw parallels to the unarmed Black men and women regularly murdered by police. The disparity between the police’s story and the Dowell family’s, the police harassment Dowell endured before his murder, the jury letting Dowell’s killer off without punishment, even the reports that Dowell had his hands raised while he was gunned down, eerily echo the police killings today that have led to the explosion of the movement for Black lives.

Yet when we learn about the early years of the Panthers, the organizing they did in Richmond — conducting their own investigation into Dowell’s death, confronting police who harassed Dowell’s family, helping mothers in the community organize against abuse at the local school, organizing armed street rallies in which hundreds filled out applications to join the party — is almost always absent.

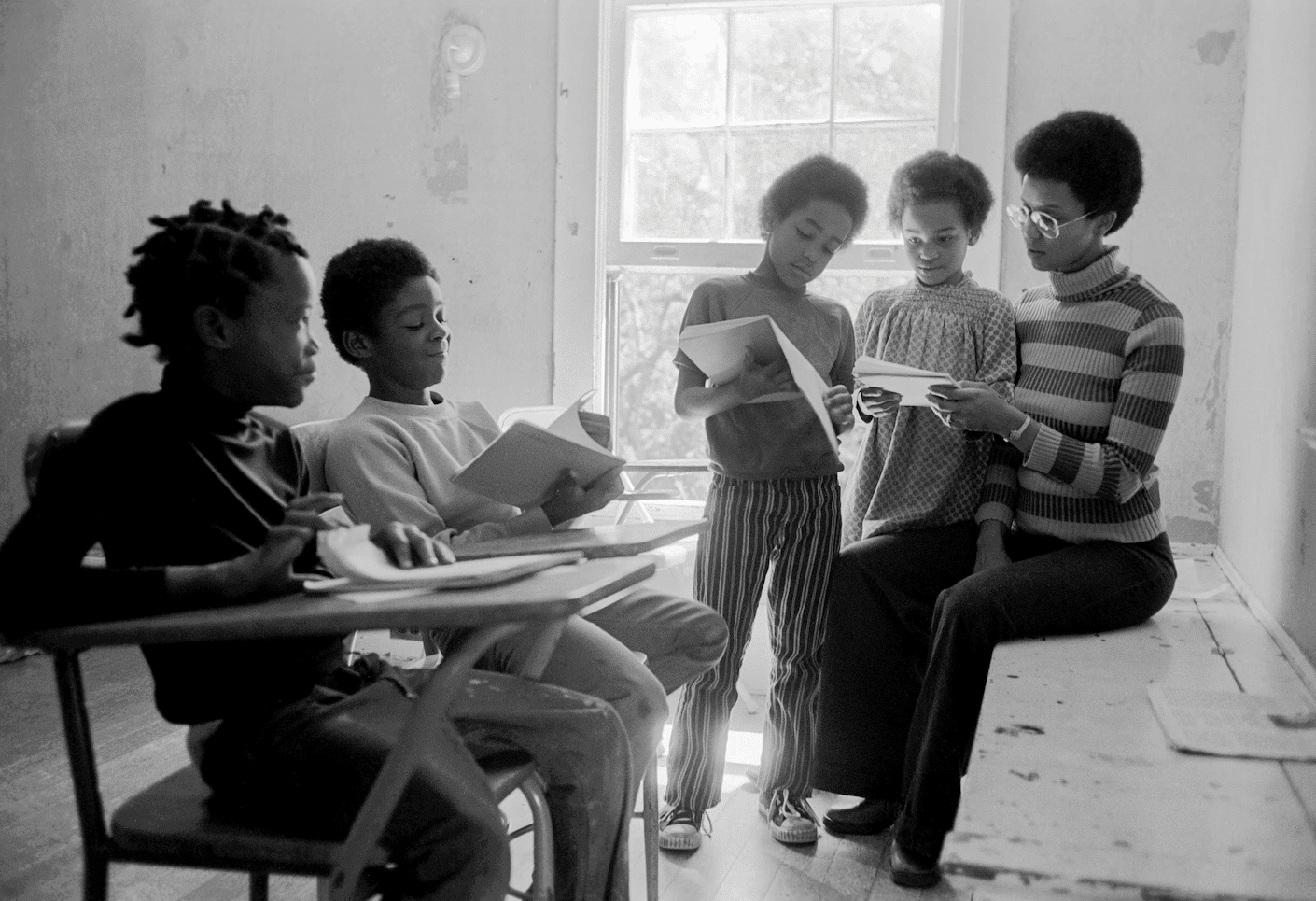

A teacher leads his students with the black power salute and slogans at a Black Panther liberation school.

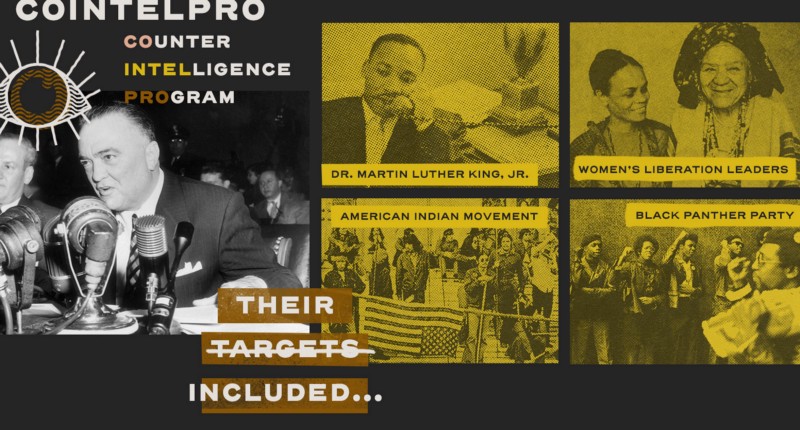

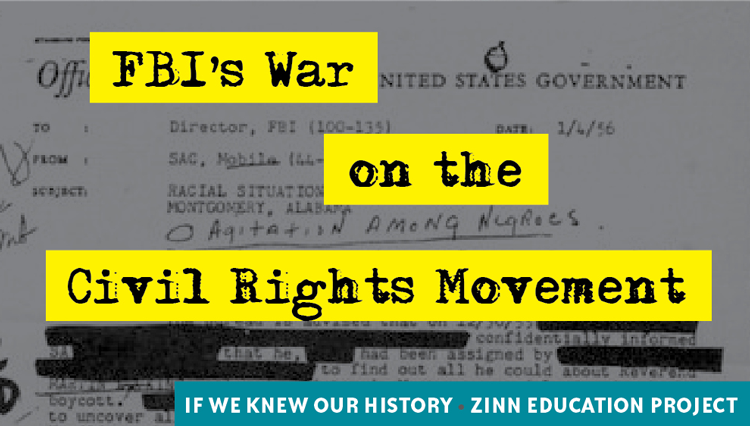

The history of the Black Panther Party (BPP) holds vital lessons for today’s movement to confront racism and police violence — yet textbooks either misrepresent or minimize the significance of the Panthers. Armed with a revolutionary socialist ideology, they fought in Black communities across the nation for giving the poor access to decent housing, healthcare, education, and much more. And as the Panthers grew, so did the issues they organized around.

The roles included for this mixer are:

| Ruby Dowell | Ericka Huggins |

| Aaron Dixon | J. Edgar Hoover |

| Donald Mulford | Huey Newton |

| Luke Tripp | Bobby Seale |

| Eldridge Cleaver | Los Angeles Police Officer Pat McKinley |

| Kathleen Cleaver | Lil’ Bobby Hutton |

| JoNina Abron | David Hilliard |

| Roberta Alexander | Stokely Carmichael |

| Jose “Cha-Cha” Jimenez | Elaine Brown |

| Emory Douglas | William “Preacherman” Fesperman |

| Lumumba Shakur | Assata Shakur |

| Fred Hampton | Angela Davis |

| Gloria Arellanes | Richard Aoki |

| Afeni Shakur | Madonna Thunder Hawk |

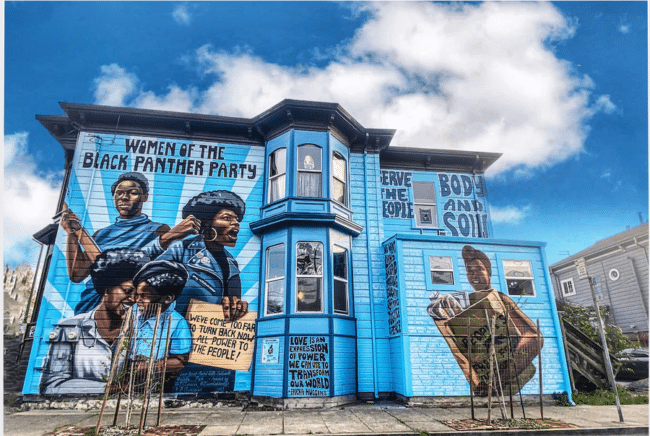

Finished in June 2021, this mural is the only public art installation in the world dedicated to the Women of the Black Panther Party (WBPP) and the 65+ Survival Programs they created. Photograph by Kerri Gaston. Source: West Oakland Mural Project

Black Panthers and Community Health

Jesse Hagopian and Adam Sanchez are interviewed in With Free Medical Clinics and Patient Advocacy, the Black Panthers Created a Legacy in Community Health That Still Exists Amid COVID-19 and this short video via Time magazine.

Classroom Stories

During our second unit in seventh-grade English this year, we read Kekla Magoon’s novel The Rock and the River. As we explored the setting of the novel, 1968 Chicago, and learned more about the key role the Black Panther Party played during the Civil Rights Movement, we turned to Magoon’s nonfiction book Revolution in Our Time. I continued my search for other reliable, quality resources that would enhance the student experience and outcomes and came across Zinn Education Project lesson What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should. Up to this point in their school experience, middle school students’ knowledge of civil rights leaders is often limited to the contributions of Dr. King, Malcolm X, and Congressman John Lewis. I was glad to be able to use teaching materials that widened the scope of their knowledge and understanding.

I used the lesson and the materials included to create a learning experience through which the students not only learned about key figures in the Black Panther Party but also better understood its role during that particular era. The materials and the lesson flow gave students opportunities to learn about better-known figures like Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton while building background into lesser-known activists. It also allowed them to get a better understanding of the Black Panther Party’s reach beyond California and even the United States. More importantly, it helped the students better connect the events then with the events we live through now, and the actions people took then with the actions we can take now. The interactive nature of the lesson increased engagement while allowing for growth through empathy as well.

Based on the quality of this lesson and especially the impact it had on my students, I highly recommend Zinn Education Project materials. I know I will return to them often.

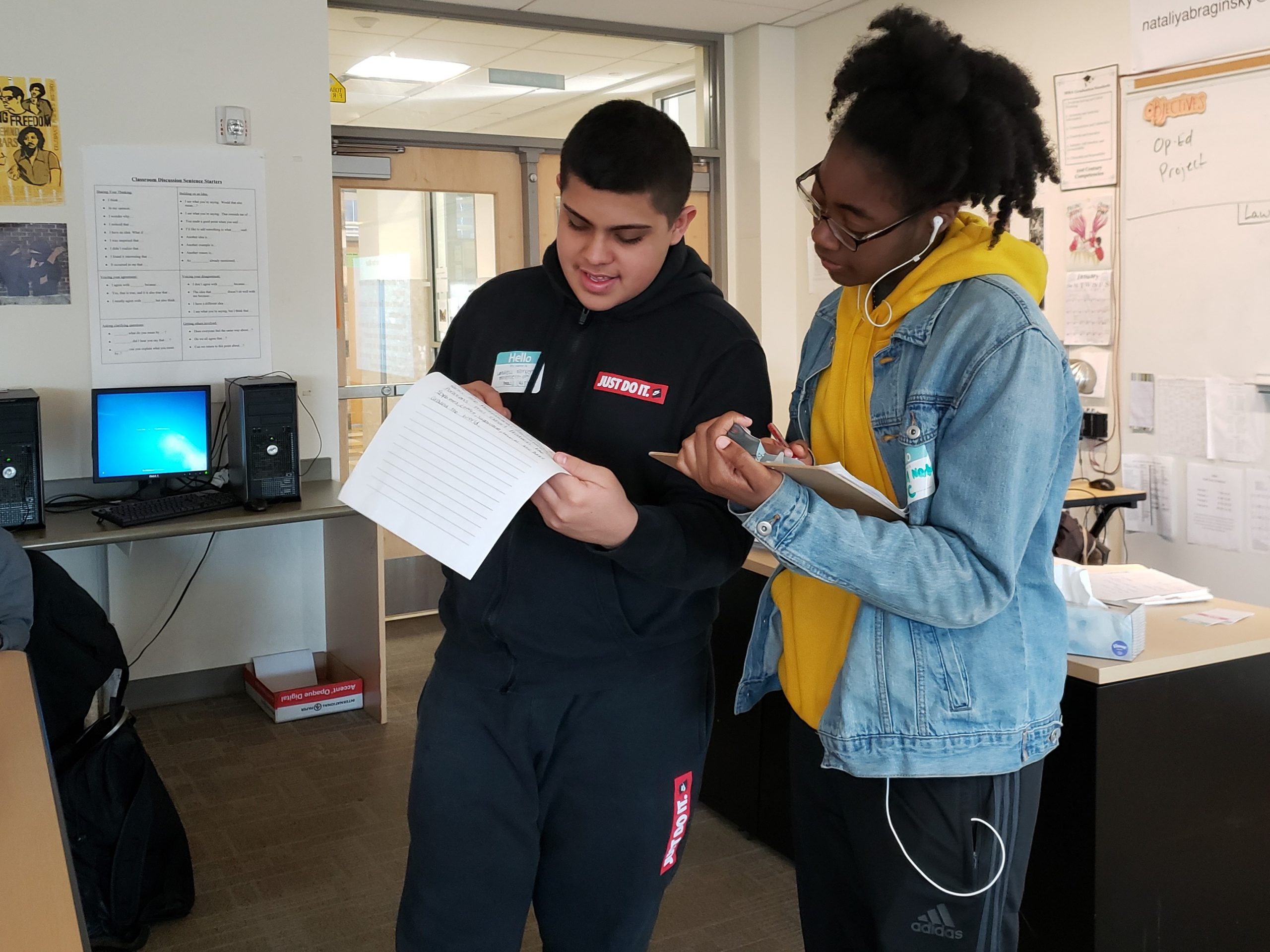

During a civil rights unit, I used the Black Panther Party mixer activity in conjunction with our lessons on the Black Panther Party. The students were familiar with mixers, but this particular mixer really grabbed students’ attention and interest. The number of roles, the incredibly diverse experiences, and the connections to other social movements allowed all of my students to see themselves and their history in the activity. It was a powerful activity that students engaged deeply with and seemed to truly enjoy.

As an Ethnic Studies history teacher I have used multiple different lessons and activities from the Zinn Education Project. I have used lessons including Simulating Redlining, Independence or Catastrophe? Teaching Palestine Through Multiple Perspectives, Deportations on Trial, Who Fought to End Slavery? Meet the Abolitionists, and What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should. The most popular one with my students was Deportations on Trial, because students were so invested in it and took their preparation and learning so seriously. I went to lunch the day before our trial to see one student talking with multiple administrators about her defense strategy for the next day.

What I love about these activities is that they are so highly adaptable. For instance, with the Black Panther Party lesson, I did a short introduction with students, had them take some notes on their accomplishments, and then we did a gallery walk in the hallway. This allowed them to read on their own time and did not push shy students into having to talk about something they might not be super comfortable with. I have also started printing out packets of the mixer roles when I do them, so that there is that option if a student would prefer to read to themselves quietly.

Another thing I appreciate is that the learning is typically very communal whenever we do these activities. If students are stuck trying to find a person who did something in particular, we will ask the class if anyone could answer the questions.

I appreciate how these activities are engaging, multi-faceted, and relational and how they allow students to dive into the depth of a topic by learning about specific historical actors who dominant narratives traditionally leave out.

Lastly, as someone who always strives to learn more about our histories, I learn something new every time I do these activities. Thank you all so much for the immense amount of labor, time, and energy it surely must take to put them together. I look forward to continuing to use these resources and others in the future.

This lesson was originally published in the Rethinking Schools publication Teaching for Black Lives.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn