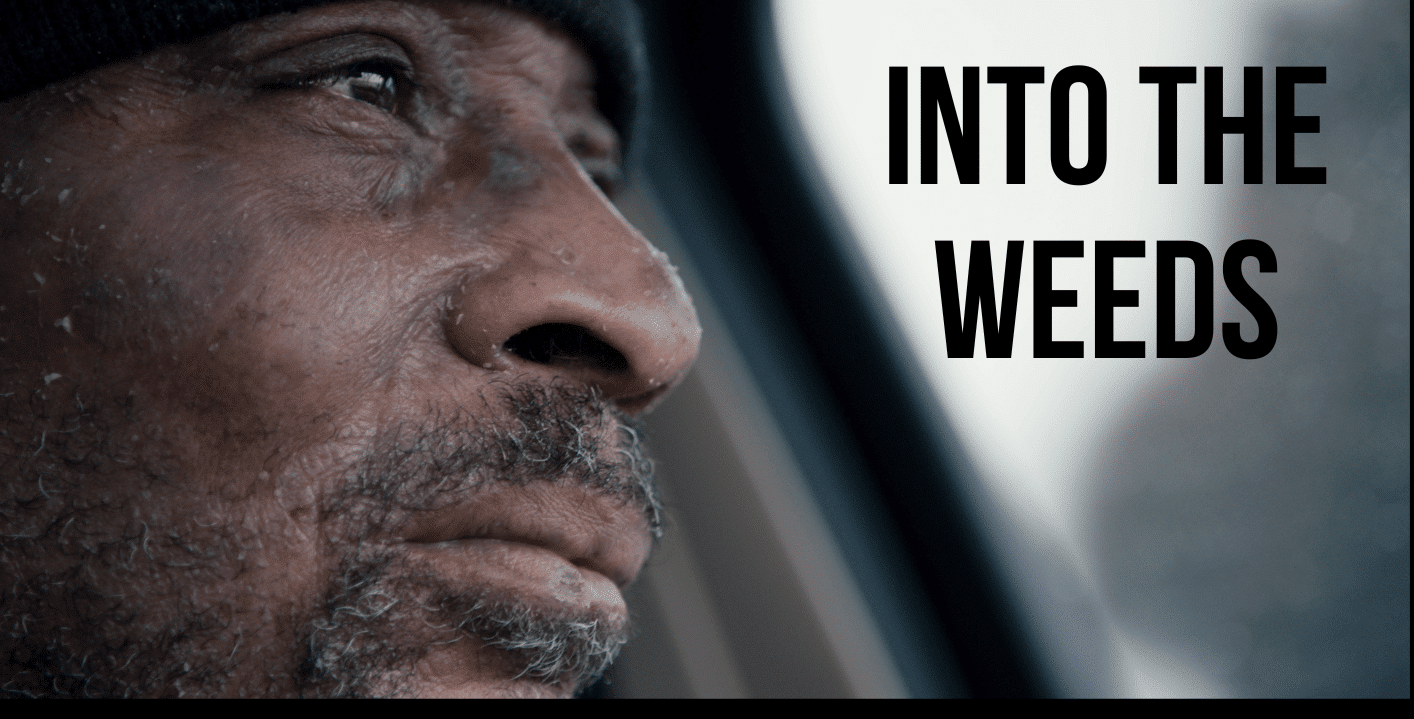

Michele Roberts, environmental justice coordinator, Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, D.C. Source: www.dicksimon.com.

By Alma Anderson McDonald

Since Hercules closed its doors in 2009, there had been talk around town that there could possibly be a lawsuit filed by the city against the company for environmental pollution. So it came as no surprise to me when in 2013 I received my letter to attend a meeting for a class action lawsuit against Hercules and its parent company, the Ashland Company.

The meeting was two weeks later on a Thursday at Lake Terrace Convention Center. When we entered the building, we were directed toward two lines: one for just property owners and one for property owners with medical claims. Though non-property owners with medical conditions were allowed to come to the meeting, this phase of the suit was only for property owners with or without medical claims. Non-property owners could not file a claim on this case and would have to wait until a secondary lawsuit was filed in the future. I was glad my claim was just as a property owner without a medical condition.

Once I made it to the front of the line, the lady at the table asked for my address.

Once I made it to the front of the line, the lady at the table asked for my address.

“203 West 7th Street,” I said.

At which she let out a long “Oooo,” and said, “Yeah, you’re right in the area.”

I didn’t like the sound of that. So, I signed my name and took the forms that she handed me and went into the large conference room.

The number of people who were there surprised me. We all had this look on our faces that was a mixture of hope, fear, concern, and anger. As we waited for the meeting to begin, I overheard some telling stories of their experiences or those of relatives who had lived in Hattiesburg their whole lives.

Download lesson to continue reading.

Classroom Stories

I love the Zinn Education Project’s resources. I teach environmental science and biology. These resources are imperative for fostering critical reflection and interrogation in us all about environmental issues and how they adversely affect some more than others, particularly racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically minoritized people in our Buffalo community.

I have used the article, “The Big Red Dot of Environmental Racism” by Alma Anderson McDonald as an introduction to environmental science and to situate our course’s attention to environmental justice. Students are familiar with the term, racism, mostly from an interpersonal standpoint. However, we begin to unpack racism in structural, institutional terms.

We take our discussion of racism further by exploring environmental racism, which this article helps make more concrete. Students often have not heard of environmental racism prior to this lesson. Students share places they love — their house, mountains in another state which they have visited, the beach, a local park, etc. This activity serves as an icebreaker as we get to learn more about each other.

McDonald’s article is accessible and full of imagery; overall, students enjoy reading it. While students initially do not consider our community as toxic as Hattiesburg, after discussion and exploration of local data — from pollutant concentrations and GIS — they begin to recognize that certain portions of our community are more adversely impacted. They ponder medical ailments, from asthma to cancer and their frequencies.

Students are amazed at how much they have not learned about their local environment and ways it has been environmentally degraded over the years. This lesson serves as an excellent branching off point for further exploration throughout the course.

Our school is located in an overwhelmingly white, affluent rural town bordering a national park. It would be an understatement to say our community is isolated from much of the environmental and racial issues plaguing our country today. Not only does The Red Dot of Environmental Racism lesson by Alma Anderson McDonald plainly define environmental injustice for my students, but it also opens their eyes to the fact that these issues are not only playing out in far-flung, developing countries, but also in their own backyard.

In addition, I think the lesson really drives home the idea that environmental injustice is not a thing of the past, but rather something that must be addressed today. It is one more way that our nation has institutionalized racism.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn