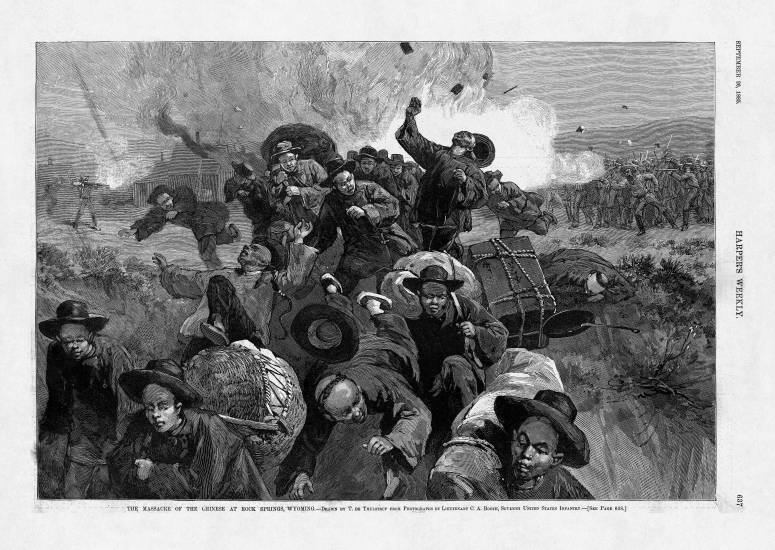

Here are more than 20 Asian Americans and events of note in people’s history for the curriculum and as a starting point for students to do further research.

We also recommend reading “Dear Educators, It Is Time to Fight for Asian America” by Wayne Au and Moé Yonamine in Rethinking Schools, the list of recommended titles for pre-K to 12 about Asian Americans at Social Justice Books, 11 Moments From Asian American History That You Should Know by Olivia Waxman and Paulina Cachero, and A Young Organizer’s Guide to Asian American Activists by Jess Eng.

To suggest a name or event to be added to this list, email zep@zinnedproject.org.

Eqbal AhmadA Pakistani political scientist, writer, editor, and antiwar activist, Eqbal Ahmad was born in 1933 and moved to the United States in the 1950s, where he attended Princeton University, taught at Cornell University and the University of Illinois, and was a fellow at the D.C.-based Institute for Policy Studies. Ahmad has been a longtime proponent of Palestinian autonomy and was an ardent opponent of the Vietnam War. In 1971, Ahmad and six others known as the Harrisburg Seven were unsuccessfully charged with conspiracy to kidnap National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and bomb critical infrustracture. All other defendants were priests or nuns, while Ahmad described himself as the odd man out of the group. Ahmad wrote extensively after retiring from teaching in 1997, and he passed away in 1999. Read The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad and Confronting Empire to learn more. |

|

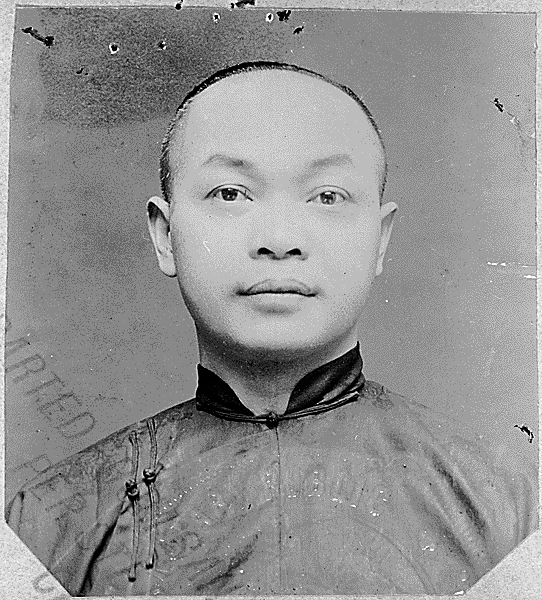

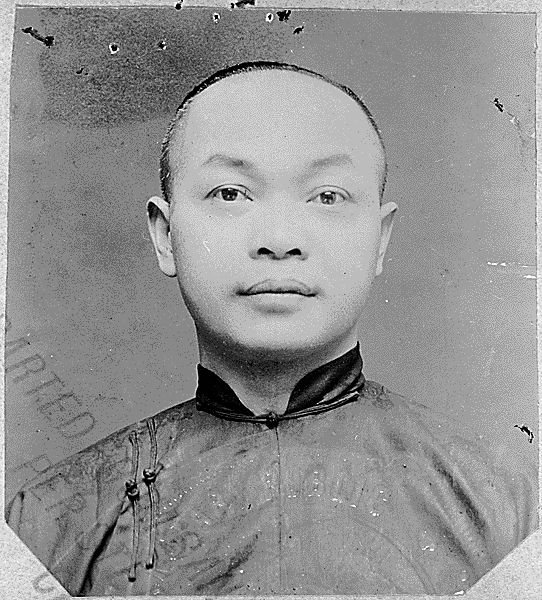

Wong Kim Ark, in a photograph taken from a 1904 U.S. immigration document. Source: Wikicommons |

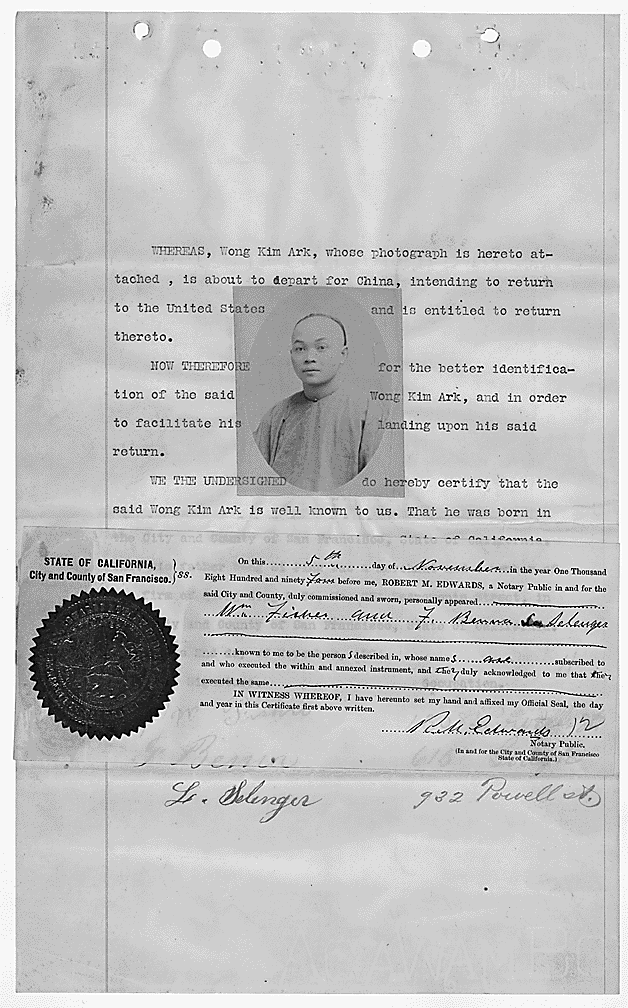

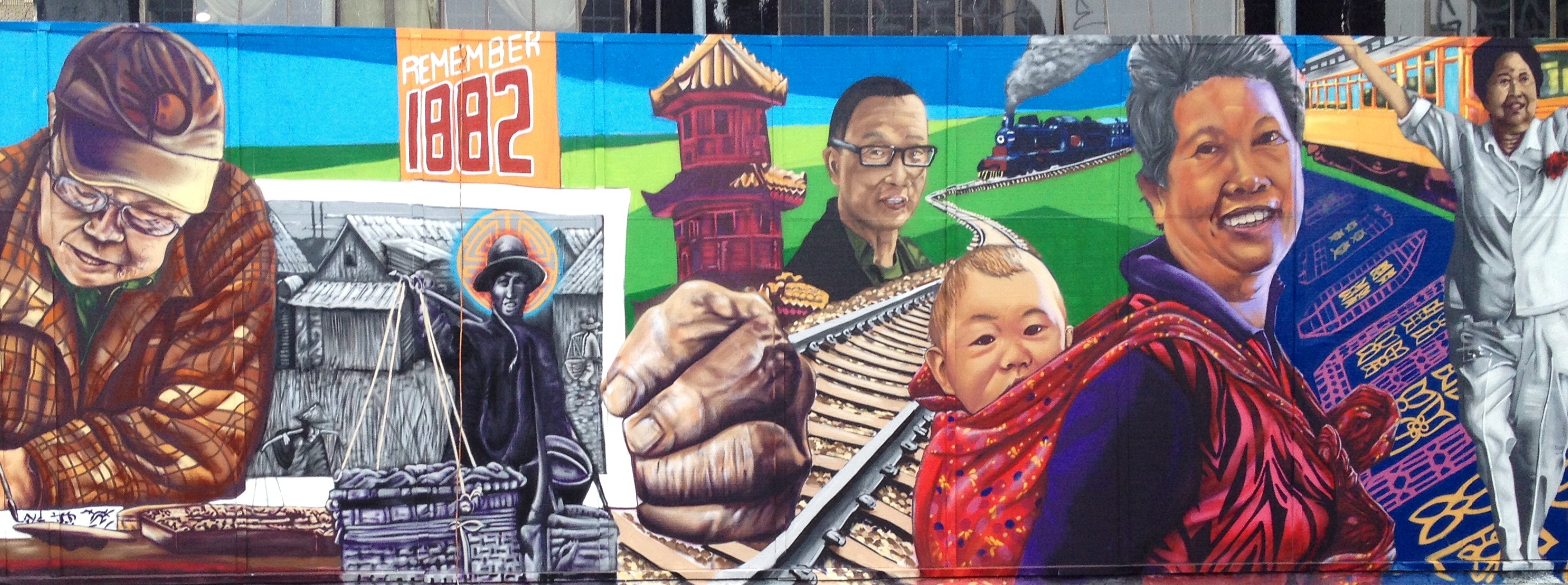

Wong Kim ArkOn March 28, 1898, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, holding that children born in the United States, even to parents not eligible to become citizens, were nonetheless citizens themselves under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Born in San Francisco to Chinese immigrants who were barred from ever becoming U.S. citizens under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, Wong Kim Ark was denied re-entry to the United States after a trip to China, on the grounds that the son of a Chinese national could never be a U.S. citizen. Wong sued the federal government, resulting in the Supreme Court’s seminal decision that the government could not deny citizenship to anyone born in the United States. [Adapted from Asian Americans Advancing Justice and PBS’s “Becoming American: The Chinese Experience.”]  Sworn statement of witnesses verifying departure statement of Wong Kim Ark, 11/02/1894. Source: Wikicommons Read the 1882 Exclusion Act at OurDocuments.gov.

|

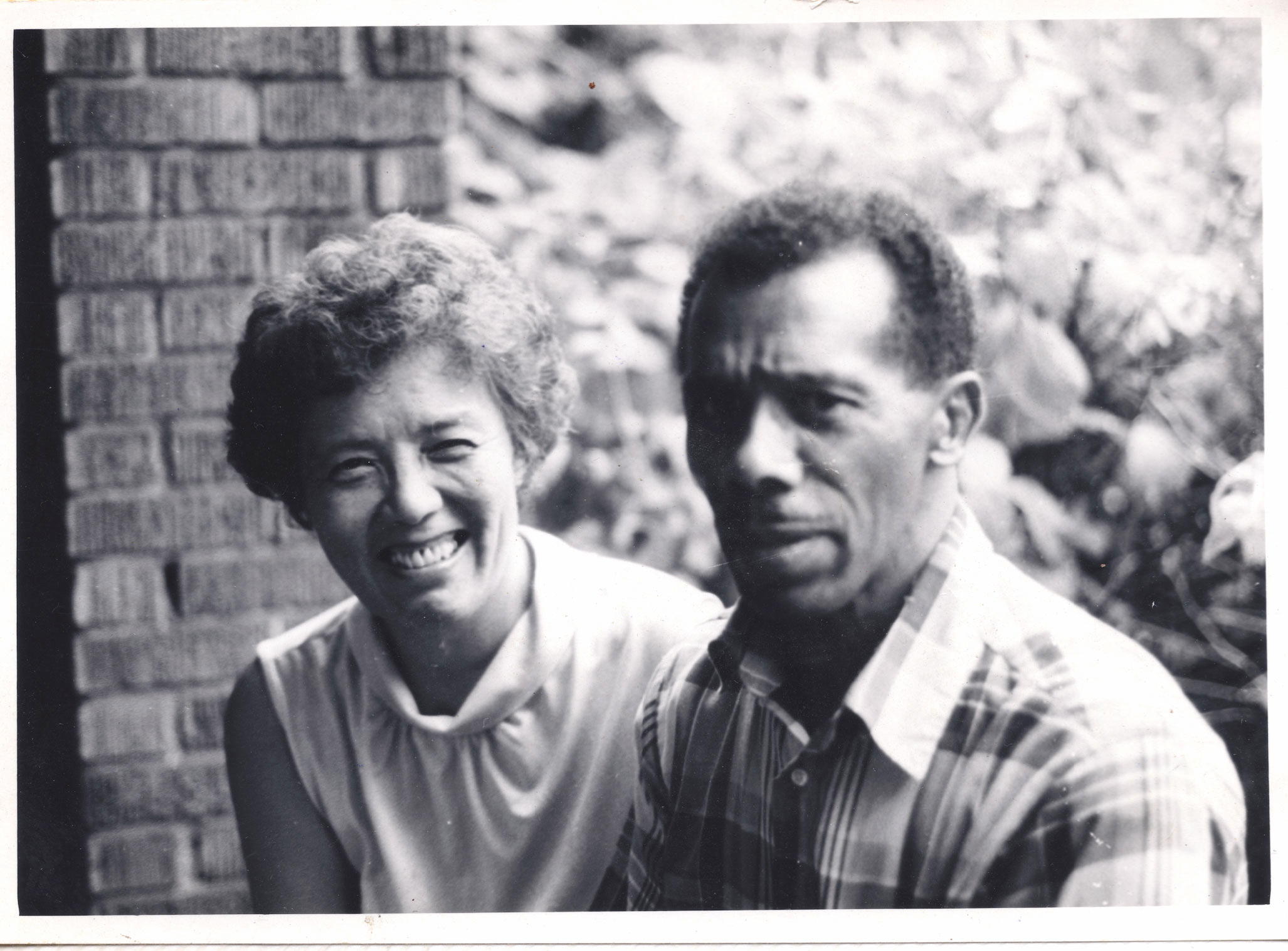

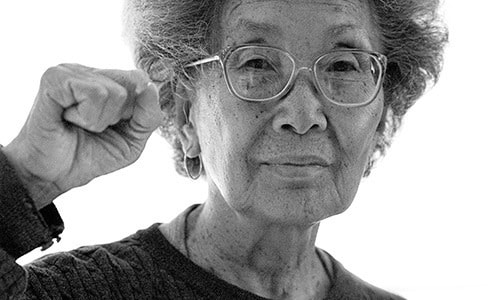

Grace Lee BoggsA prominent activist her entire adult life, Grace Lee Boggs (June 27, 1915 – October 5, 2015) was born in Rhode Island, the daughter of Chinese immigrants. She studied at Barnard College and Bryn Mawr, receiving her Ph.D. in 1940. Her studies in philosophy and the writings of Marx, Hegel, and Margaret Mead led not to a life in academia, but rather to a lifetime of social activism. Lee’s activism began in Chicago, where she joined the movement for tenants’ rights, and then the Workers Party, a splinter group of the Socialist Workers Party. In these associations, as well as in her involvement with the 1941 March on Washington, Lee focused on marginalized groups such as women and people of color. In 1953, Lee married Black auto worker and activist James (Jimmy) Boggs and moved to Detroit, where the two continued their activism. Jimmy died in 1993. Boggs has rejected the stereotypical radical idea that capitalist society is just something to be done away with, believing more that “you cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it, unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it.” She believed that it is by working together in small groups that positive social change can happen, not in large revolutions where one group of power simply changes position with another. With this philosophy, she and her husband founded Detroit Summer in 1992. In a YES! Magazine interview, Boggs explains, “We wanted to engage young people in community-building activities: planting community gardens, recycling waste, organizing neighborhood arts and health festivals, rehabbing houses, painting public murals. Encouraging them to exercise their Soul Power would get their cognitive juices flowing. Learning would come from practice, which has always been the best way to learn.” Boggs continued to write books and be an activist. She died in 2015 at the age of 100. [From Americans Who Tell the Truth.] Learn more in the documentary “American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs” and from her books, Living for Change: An Autobiography and The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century. |

|

May ChenIn 1982, May Chen led the New York Chinatown strike of 1982, one of the largest Asian American worker strikes with about 20,000 garment factory workers marching the streets of Lower Manhattan demanding work contracts. Chen, then affiliated with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, was one of the strike organizers. “The Chinatown community then had more and more small garment factories,” she recalled. “And the Chinese employers thought they could play on ethnic loyalties to get the workers to turn away from the union. They were very, very badly mistaken.” Most of the protests included demands for higher wages, improved working conditions, and for management to observe the Confucian principles of fairness and respect. By many accounts, the workers won. The strike caused the employers to hold back on wage cuts and withdraw their demand that workers give up their holidays and some benefits. It paved the way for better working conditions such as hiring bilingual staff to interpret for workers and management, initiation of English-language classes, and van services for workers. [Description by Cristina DC Pastor, from the Feet in Two Worlds website.]

Read more about Asian immigrants in the workforce at the Feet in Two Worlds website. |

|

Ibrahim Chowdry, a Bengali community organizer in New York. Source: Hyphen.com |

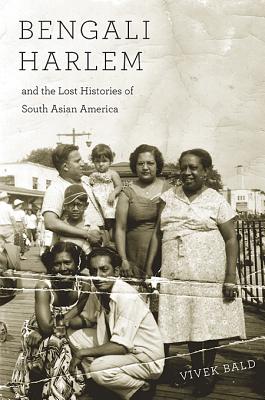

Ibrahim Chowdry“I talk for those of our men who, in factory and field, in all sections of American industry, work side by side with their fellow American workers to strengthen the industrial framework of this country.”— Ibrahim Chowdry, in a letter given for testimony during the U.S. Congressional Committee on Immigration and Naturalization hearings in 1945 Ibrahim Chowdry was a community organizer in New York, who worked across racial and religious lines to build coalitions between Bangladeshi immigrants and Puerto Rican and Black communities. Chowdry escaped a British crack down over his political activities in East Bengal and settled in New York City in the 1920s, where he and his fellow East Bengalis initiated numerous community organizations which included pooling their money to help open restaurants and small businesses, starting organizations to empower their communities, and offering social support for new immigrants who moved in.

Read more about the history of South Asian Americans in Vivek Bald’s book, Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. |

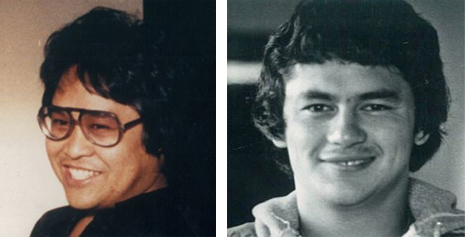

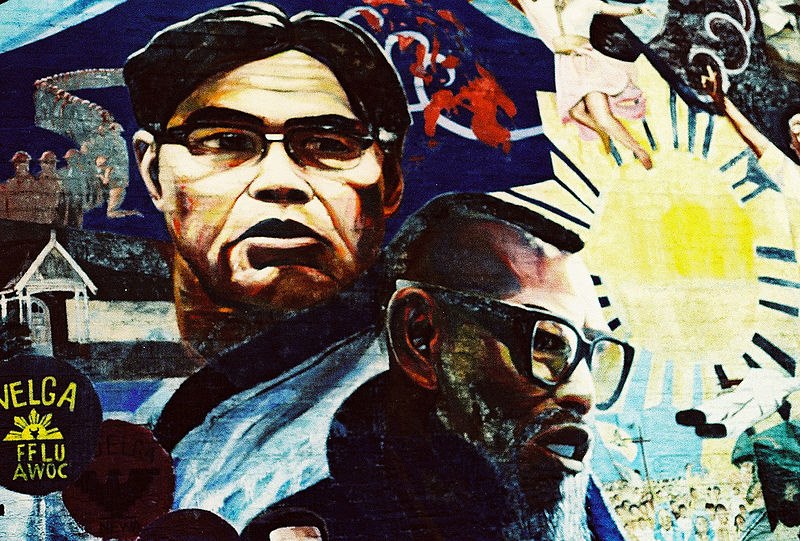

Silme Domingo & Gene ViernesIn 1981 the labor leaders Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes were gunned down in a drive-by shooting. Domingo and Viernes were Filipino American activists and fishing cannery Local 37 union members who were involved in union reform and fighting for workers’ rights. In an effort to address the discrimination and segregation towards Filipinos that had been going on for decades in the Alaskan seafood industry, organizers needed proof. Domingo and a partner posed as students from the University of Washington’s School of Fisheries and requested to document the canneries for a project. Instead, they gathered evidence of discrimination. On Nov. 28, 1973, the Alaska Cannery Workers’ Association (ACWA, which Domingo and Viernes helped found) filed a class action lawsuit against several Alaskan fish companies, including one of the largest, the New England Fish Co. (NEFCO). It was the first time such an enormous seasonal migratory labor force was represented in a significant way with more than 700 plaintiffs in all. ACWA won a multi-million dollar settlement, and as a result NEFCO filed for bankruptcy. Initially, the murders appeared to be retributions for reform efforts within Local 37 that threatened entrenched interests. But after a wide-ranging legal investigation launched by family, friends, and community groups, in 1989 a federal jury found that former Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos conspired to silence political opponents in the U.S. that resulted in the murders of Domingo and Viernes. The conspiracy involved the Marcos government, the president of Local 37, and a network of Marcos’ intelligence agents that operated within the United States since 1973, monitoring and harassing Marcos’ opponents in the United States. [From “The ‘Cannery Murders’ of 1981 still haunt local labor activists” and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union.] Learn more in the book Remembering Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes: The Legacy of Filipino American Labor Activism by Ron Chew and the documentary One Generation’s Time: The Legacy of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes. |

|

Frank S. Emi and Draft ResistersFrank Emi, a grocer from Los Angeles and Japanese-American, was an activist during World War II. He was a leading figure of the Fair Play Committee, an ad hoc group that protested the drafting of Japanese Americans during World War II, and served an 18 months sentence for refusing the draft. From the Densho Encyclopedia: On March 25, 1944, U.S. Marshals arrested twelve young men at Heart Mountain who were no-shows for their draft physicals but that did not put an end to resistance. As dozens more refused to report, Emi and two other FPC leaders attempted to walk out of camp without a pass to prove that they were indeed prisoners. In all, sixty-three Heart Mountain resisters were found guilty on one count each of draft evasion and sentenced to federal prison… Convicted of conspiracy to violate the Selective Service Act, Emi served 18 months in a federal penitentiary. Emi later explained: “I could not believe that the government could actually put us in camp, strip us of everything . . . and then order us into the military as if nothing had happened.” He added, “We could either tuck our tails between our legs like dogs or stand up like free men and fight for justice. Some of us chose the latter. We were going to resist.” Learn more about Frank Emi’s interrogation while incarcerated in Wyoming. |

|

Executive Order 9066On Feb. 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 was issued by President Franklin Roosevelt. It authorized the incarceration (internment) of U.S. citizens of Japanese descent. About 122,000 people were sent to concentration camps. Many of their homes, businesses, and farms were confiscated. We refer to the internment as incarceration. This choice of language is recommended by the Densho Encyclopedia, because “One of the strategies employed by the federal government to sell the forced removal and confinement of Japanese American from the West Coast during World War II was the use of euphemistic terms that masked the true nature of what was being done.” Read their full statement, Do words matter? Learn more about the incarceration of Japanese-Americans in our This Day in History entry for Feb. 19. |

|

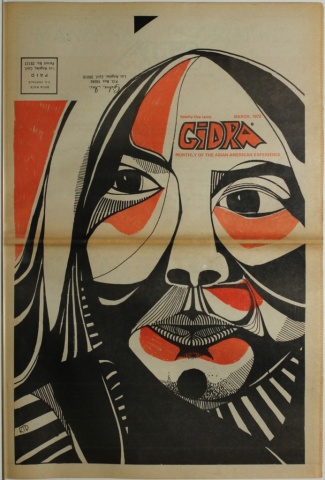

GidraDuring its 1969 to 1974 run, Gidra chronicled the dramatic changes in the Asian American community, and was itself a catalyst for many of these changes. The roots of Gidra stem from a group of students at UCLA who approached the administration about starting an Asian American community newspaper in 1969. Rebuffed, the five each kicked in $100 to produce their own paper. Tracy Okida came up with the name, which came from a giant three-headed dragon from Japanese monster movies of the 1960s. Initially based at the newly formed Asian American Studies Center at UCLA, Gidra helped define the terms of the Asian American Movement for many and covered the fight for ethnic studies on college campuses, along with rising activism in Asian American communities. Though pan Asian American in its orientation, it was largely a Sansei enterprise with three-quarters or more of the staff being Japanese American. As the publication evolved and moved off campus to an office in the Crenshaw District of Los Angeles, its scope broadened to encompass an Asian American perspective on the international anti-imperialist movement, linking the war in Vietnam to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to other movements in Asia including Okinawa, the Philippines, and Korea. [From the Densho website.] Continue reading about the history of Gidra newspaper by Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director. View the online archives at the Densho Digital Repository. |

|

|

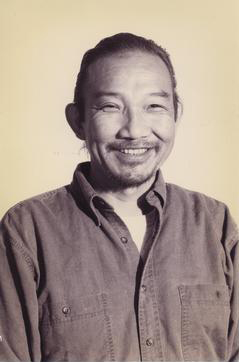

Fred HoBorn in 1957, Fred Ho was a composer, a saxophonist, and an activist for Indigenous and traditional music. A creator of Asian American avante-garde jazz, Ho was active in “the burgeoning Asian American movement, first joining the Black Panther-inspired I Wor Kuen before founding the East Coast Asian American Student Union in 1978 and the Asian American Resource Workshop in Boston in 1979.” Ho co-edited four books, including Sounding Off! Music as Subversion/Resistance/Revolution, Legacy to Liberation: Politics and Culture of Revolutionary Asian Pacific America, Afro Asia: Revolutionary Political and Cultural Connections between African Americans and Asian Americans, and Maroon the Implacable: The Collected Writings of Russell Maroon Shoatz. Fred Ho passed away in 2014 after an eight-year battle with cancer. The article Remembrance/Revolution: A Tribute to Fred Ho to learn more. |

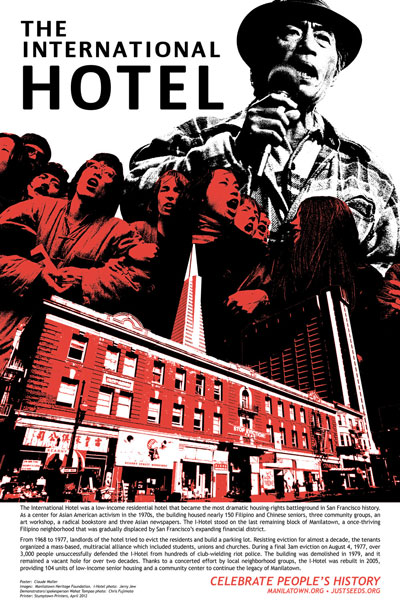

Poster by Claude Moller, justseeds.org |

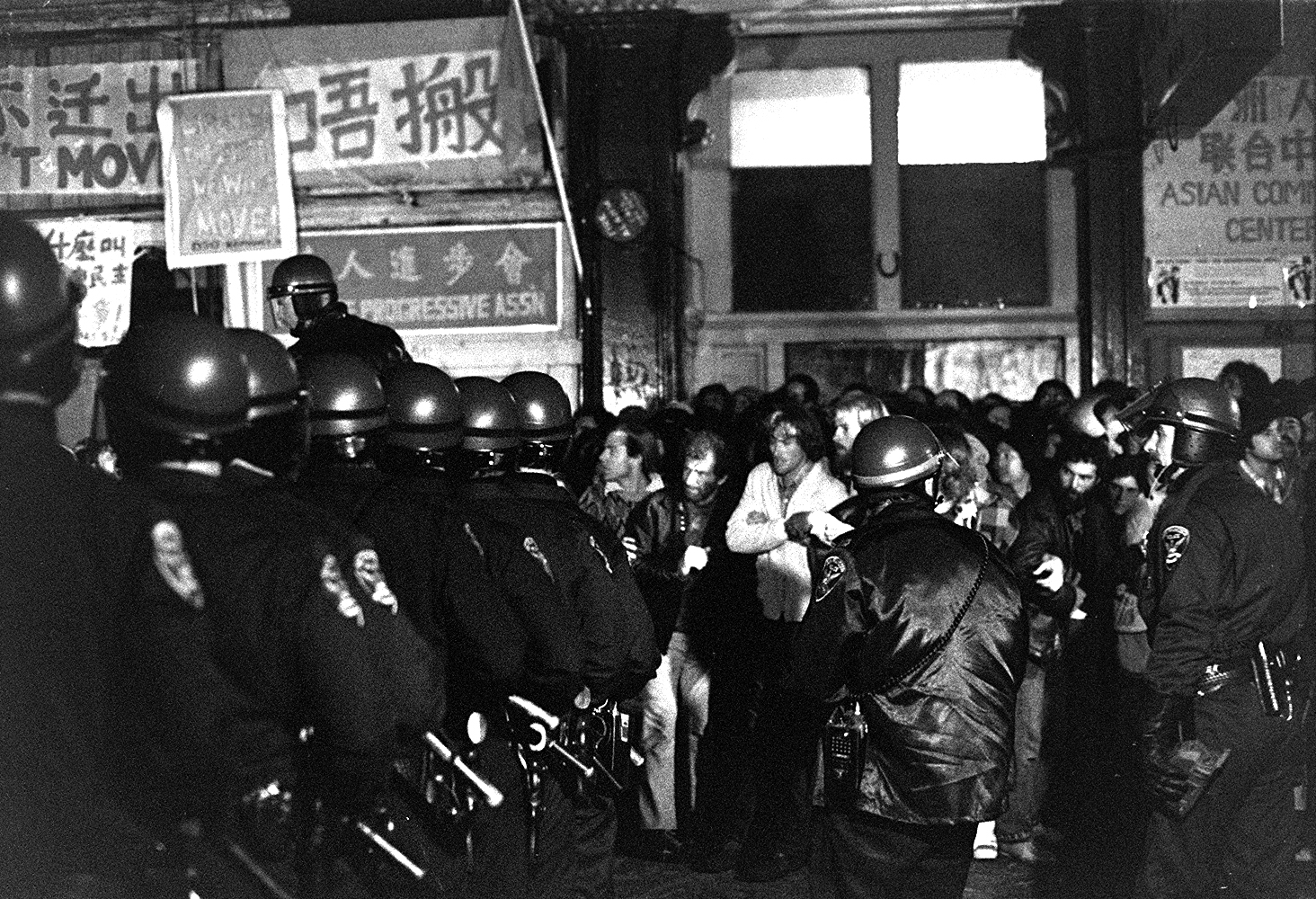

The International Hotel StruggleOn August 4, 1977, after battling eviction for over nine years, the community of mostly Filipino and Chinese low-income senior tenants of the International Hotel (I-Hotel) was brought to a violent end in the early morning hours. At around 4 a.m., over 300 riot-equipped police and sheriff’s deputies, cordoned off the surrounding streets, encircled the hotel, and began to forcefully evict the residents. De Guzman, then the president of the International Hotel Tenants Association, described what happened: Once the police and sheriffs got into the building, they broke into the tenants’ rooms. Then they started breaking things up, stealing, taking what the manongs [Filipino males] had, broke the toilets that way there were no toilet facilities, so the tenants could never return.  August, 1977: San Francisco Sheriffs’ deputies and police confront demonstrators trying to prevent forced eviction of the hotel’s elderly tenants. Source: Nancy Wong/ WikiCommons Outside, more than 2,000 community activists and protesters created a human barricade trying to prevent the eviction. Shouting “We won’t move!” I-Hotel defenders—that included not only Filipinos but other Asian Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, student activists, religious groups and organizations, gays and lesbians, leftists, and community activists — lined up nine rows deep as the police started their frontal assault. The police were brutalizing people outside in front of the hotel, said De Guzman. They would run their horses up front and hit people with their clubs. They just tore people up, hitting them on the head, and jabbing them with nightsticks. The building was eventually sold with plans to build a parking garage. However, the lot remained empty, and in 2005 a new International Hotel — now on the register of historic buildings — was built containing 105 low-income apartments for senior housing, thanks to the ongoing activism and advocating for fair housing. [Adapted from James Sobredo’s “The Battle for the International Hotel” and “I-Hotel Eviction Summary” posted on FoundSF.org.] Read more at ShelterForce and Manilatown Heritage Foundation’s “International Hotel’s Final Victory [PDF]”. Browse lessons on housing and displacement. |

Source: WikiCommons |

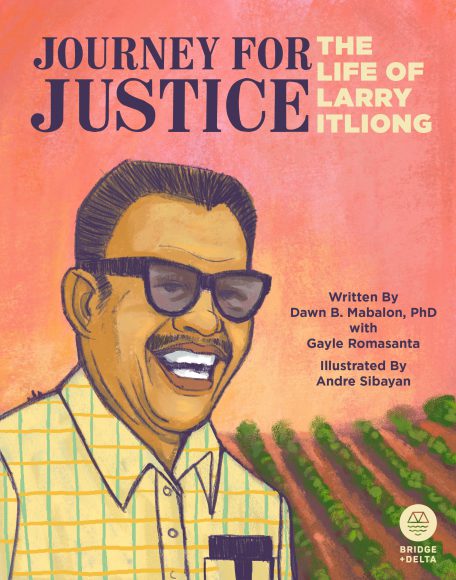

Larry ItliongBorn in San Nicolas, Pangasinan in 1913, Larry Itliong immigrated to the United States in 1929 and worked as a laborer and farmhand in several states including Washington, Alaska, Montana, South Dakota, and California. During his time in Alaska, he earned the nickname “Seven Fingers” after losing three of his fingers in an accident at the cannery where he worked. Seeing the plight of his fellow Filipinos and immigrants who were mistreated and paid poorly, Itliong joined strikes and helped set up labor unions including one in Alaska. On September 8, 1965, Larry Itliong, a member of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, called a strike against the Delano, California, grape growers in order to demand salaries equivalent to the federal minimum wage and the right to form their own union. Led by Itliong, more than one thousand Filipino workers walked out of their grape farms to picket, however, farmers replaced them with Mexican workers. As fellow striker Andy Imutan recalls, “There was no unity between the Mexicans and the Filipinos. The growers were very successful in dividing us and creating conflict between the two races. Larry Itliong and I decided to take action by seeing Cesar Chavez, the leader of the National Farm Workers Association. We met to come up with a plan that would be beneficial for everyone, including the Mexican workers.” A week after the strike, they were joined by the Mexican-dominated National Farm Workers led by Cesar Chavez. The two groups merged together to create the United Farm Workers Union, with Cesar Chavez as director and Larry Itliong as assistant director. This strike would be known as the Delano Grape Strike of 1965 and would last five years. Watch a remembrance clip from Asian Americans Advancing Justice. Since 2015, October 25 in California is known as Larry Itliong Day. Learn more about Larry Itliong in the documentary “The Delano Manongs” and in the NPR news report, “Grapes of Wrath: The Forgotten Filipinos Who Led a Farmworker Revolution.” |

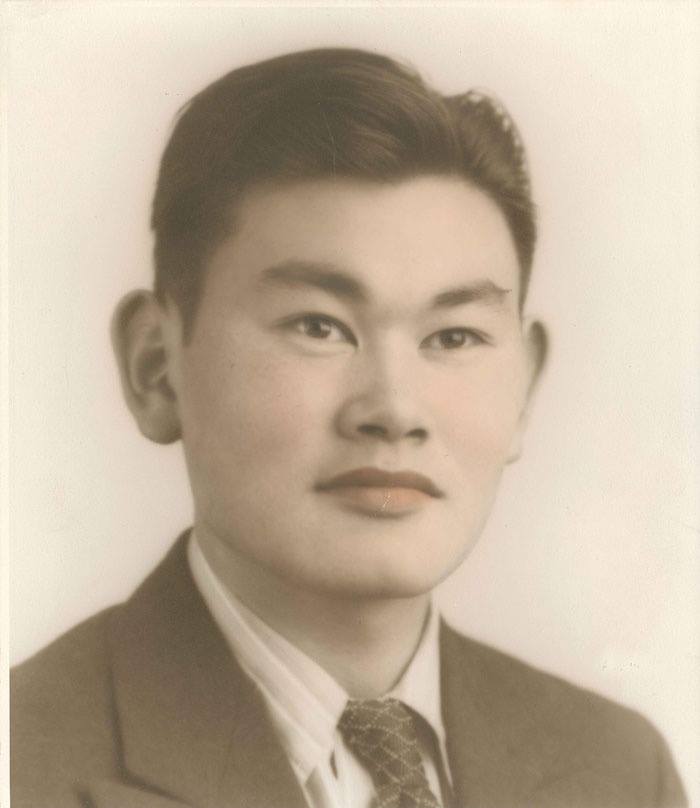

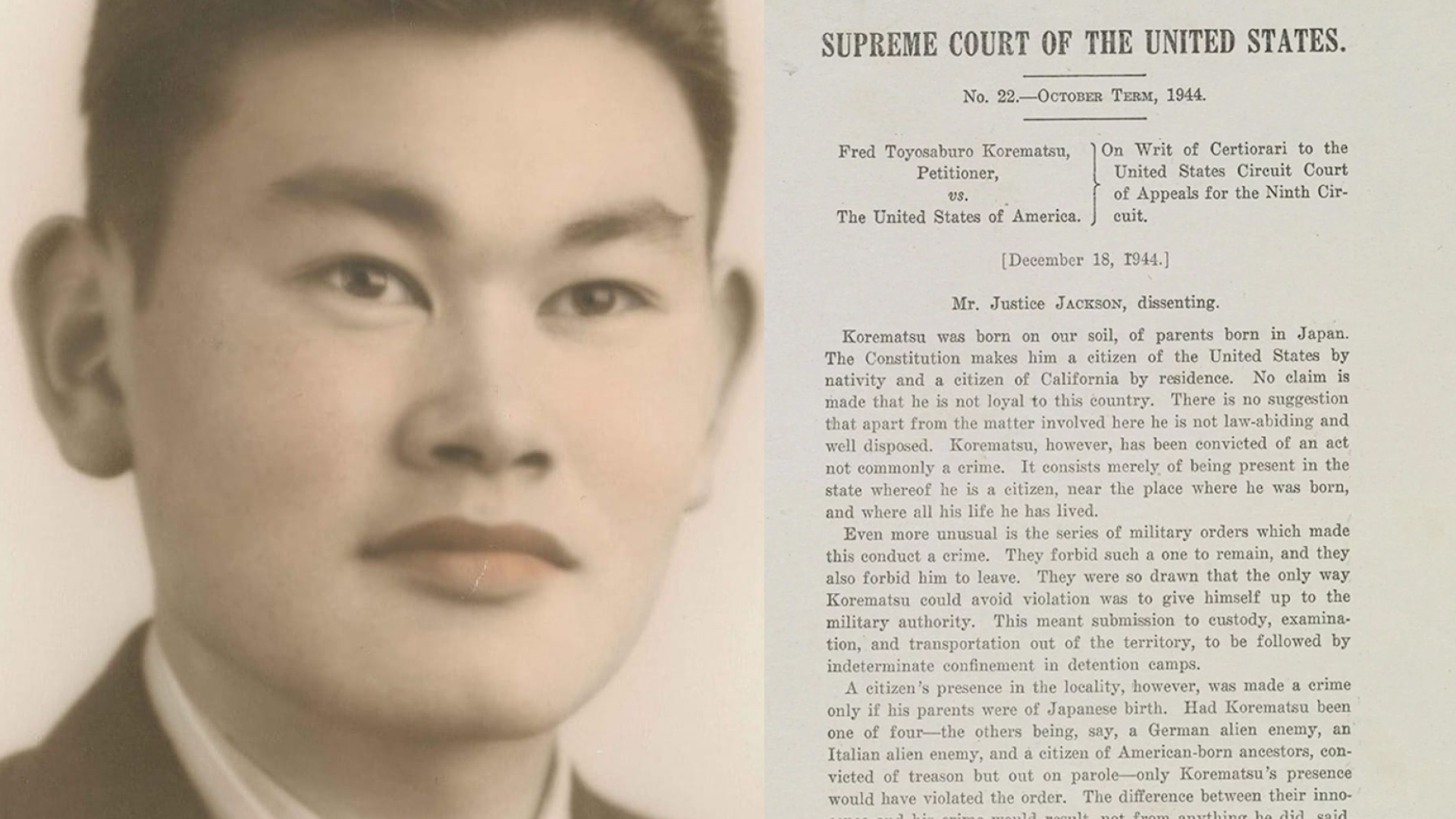

Fred KorematsuFred Korematsu (Jan. 30, 1919–Mar. 30, 2005), a U.S. citizen and the son of Japanese immigrants, had refused to evacuate when President Roosevelt ordered the internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII. Korematsu, age 23, was arrested, convicted, and sent to the Topaz Internment Camp in Utah. Persuaded by Ernest Besig, then executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Northern California, Korematsu filed a case on June 12, 1942. The premise of the lawsuit was that Korematsu’s constitutional rights had been violated and he had suffered racial discrimination. However, the court ruled against Korematsu and he was sentenced to five years probation. Determined to pursue his cause, Korematsu filed an appeal with Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and, later, to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1944, in Korematsu v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled against him, and confirmed that the denial of civil liberties based on race and national origin was legal. In 1983, Prof. Peter Irons, a legal historian, together with researcher Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, discovered key documents that government intelligence agencies had hidden from the Supreme Court in 1944. The documents consistently showed that Japanese Americans had committed no acts of treason to justify mass incarceration. With this new evidence, a pro-bono legal team that included the Asian Law Caucus re-opened Korematsu’s 40-year-old case on the basis of government misconduct. On November 10, 1983, Korematsu’s conviction was overturned in a federal court in San Francisco. It was a pivotal moment in civil rights history. [From the Fred T. Korematsu Institute website and Of Civil Wrongs and Rights website.] On Jan. 30, 2011, the state of California celebrated Fred Korematsu Day, the first day named after an Asian American in the United States, now recognized by six states. Learn more about the case and additional resources on the Japanese internment. |

|

Yuri KochiyamaYuri Kochiyama (May 19, 1921 – June 1, 2014) was a tireless political activist who dedicated her life to contributing to social change through her participation in social justice and human rights movements. She was born and raised in San Pedro, California. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, her father, just out of surgery, was arrested and detained in a hospital. “He was the only Japanese in that hospital,” Kochiyama recalls, “so they hung a sheet around him that said, ‘Prisoner of War.'” He died shortly thereafter. In 1943, under President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, Kochiyama and her family were sent to a concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas, for two years. This experience and her father’s death made Kochiyama highly aware of governmental abuses and would forever bond her to those engaged in political struggles. After being released, she moved to New York and married Bill Kochiyama, veteran of the all-Japanese American 442nd combat unit of the U.S. Army. Kochiyama’s activism started in Harlem in the early 1960s, where she participated in the Asian American, Black, and Third World movements for civil and human rights, ethnic studies, and against the war in Vietnam. She was a fixture in support movements involving organizations such as the Young Lords and the Harlem Community for Self Defense. As founder of Asian Americans for Action, she also sought to build a more political Asian American movement that would link itself to the struggle for Black liberation. “Racism has placed all ethnic peoples in similar positions of oppression poverty and marginalization.” In 1963, she met Malcolm X. Their friendship and political alliance changed her life and outlook. She joined his group, the Organization for Afro-American Unity, to work for racial justice and human rights. Yuri was present on the day he was tragically shot and killed in 1965. In the Life magazine article “Death of Malcolm X,” she can be seen crouched in the background, cradling Malcolm X’s head. In the 1980s, Kochiyama worked in the redress and reparations movement for Japanese-Americans along with her husband Bill. Support for political prisoners — African American, Puerto Rican, Native American, Asian American, and progressive whites — has been a consistent thread in her work. [From Asian Americans Advancing Justice and Women of Hope: Asian Americans.] Learn more about Kochiyama in:

Watch this remembrance clip from Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

|

|

Source: LGBTHistoryMonth |

Kiyoshi KuromiyaBorn in the Heart Mountain, Wyoming, internment camp in 1943, Kiyoshi Kuromiya (May 9, 1943 – May 10, 2000) was a lifelong activist participating in several movements including civil rights, protesting the Vietnam War, LGBT rights, and AIDS/HIV advocacy. In 1968, as an architecture student at the Univ. of Pennsylvania, he and some friends held a demonstration against the use of napalm in Vietnam by announcing that a dog would be burned alive with napalm in front of the university library. Thousands turned up to protest, only to be handed a leaflet reading: “Congratulations on your anti-napalm protest. You saved the life of a dog. Now, how about saving the lives of tens of thousands of people in Vietnam.” Kuromiya spent the spring and summer of 1965 in the South fighting for civil rights, and became friends with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. When King was assassinated, Kuromiya helped take care of the King children. Kuromiya participated with the Gay Pioneers in the first organized gay and lesbian civil rights demonstrations, “the Annual Reminders,” held at Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell each Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969. He was one of the founders of Gay Liberation Front-Philadelphia and served as an openly gay delegate to the Black Panther Convention that endorsed the gay liberation struggle. Diagnosed with AIDS in 1989, Kuromiya became a self-taught expert on the disease, operating under the mantra “information is power.” He founded the Critical Path Project, which provided resources to people living with HIV and AIDS, including a newsletter, a library and a 24-hour phone line. [Adapted from LGBT History Month, NBC News, and ACT UP-New York.] Learn more about Kuromiya in this remembrance video by friend Alfredo Sosa. |

Corky LeeFor nearly fifty years, Corky Lee documented the lives of Asian Pacific Americans at work, at leisure, and as activists. Born in Queens, New York, to Chinese immigrants, Lee grew up seeing very few people who looked like him or shared his family’s culture and he grew into awareness of how this harmed Asian Americans living in the United States. His photography became a corrective to narratives that erased Asian Americans and a journalistic record of political activism. Lee died in early 2021 from complications due to COVID-19. In an obituary, Vulture writers Ming Lin and Alexandra Tatarsky describe his activism and rise to prominence in the 1970s: One of the earliest pictures he sold was an image of a bloodied Chinese American man named Peter Yew, who was beaten by police after trying to intervene in their assault on a Chinese teenager. It ended up on the front page of the New York Post in 1975, and 2,500 Chinatown residents marched on City Hall in protest of police brutality. Lee would show up at protests against the Vietnam War or the construction of a jail, or join picket lines with Chinatown workers protesting their exploitative employers. Rallying fellow artists and activists he met, he helped found influential community groups and collectives, including Basement Workshop.  Peter Yew police brutality protests in front of New York City Supreme Court. Source: Corky Lee/Interference Archives Learn more about Corky Lee’s photography in an exhibition review from 2013 and in the New York Times‘ series “Those We’ve Lost.” |

|

Martha and Berda LumAt the start of the school semester in September 1924, Chinese-American sisters Martha and Berda Lum were barred from attending their local middle school in Rosedale, Mississippi, and their exclusion set off a lawsuit that challenged (unsuccessfully) the “separate but equal” doctrine. Their parents, Katherine Lum and Jeu Gong Lum, were determined that their children would receive the best education available and appealed this restriction all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. Three years later, on Nov. 21, 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that state’s rights and Plessy v. Ferguson applied to Asian American students, or as the court said, students of the “yellow race.” See this story’s This Day in History post for related resources and more. |

|

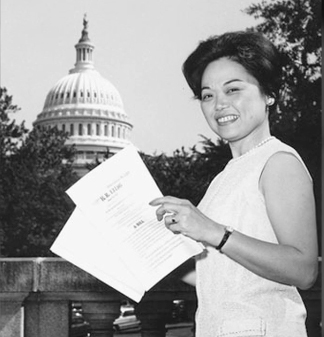

Still from the film “Patsy Mink: Ahead of the Majority.”

|

Patsy MinkCongresswoman Patsy Mink (December 6, 1927 – September 28, 2002) was the first Asian American woman elected to Congress, and ran 18 political campaigns since 1956. Through it all, Mink has consistently taken moral stands on behalf of Asian Americans, women, and children—even at potential risk to her political career. She attended the University of Nebraska and discovered that the “International House” dormitory where she was placed was designated solely for students of color because they were not allowed to live in the regular dorms. She protested and rallied the support of students, parents, and university trustees. Within months, the policy of segregated housing was abolished. Mink originally planned to attend medical school, but her 25 applications were rejected because medical schools were all male. Instead, she went to the University of Chicago law school, married John Francis Mink, and had a daughter, Wendy. The family returned to Hawaii after Mink’s graduation, when in 1953, she became the first Japanese American woman admitted to the practice law in Hawaii. However, she could not find work as women were expected to be full-time mothers. Determined to practice law, Mink set up her own law office. In 1956, she ran for the House of Representatives, won, and established herself as an independent voice. On her very first day, she offered a resolution protesting British nuclear testing in the South Pacific; the resolution passed. Mink was selected to speak at the 1960 Democratic National Convention. In her speech to the convention, she stated, “If to believe in freedom and equality is to be a radical, then I am a radical.” During her 12-year congressional tenure, she consistently voted for a progressive agenda. She introduced the first comprehensive Early Childhood Education Act (later vetoed by President Richard Nixon), authored the Women’s Educational Equity Act, criticized the Vietnam War, and spoke out against the secret bombing of Southeast Asia. In 1972, Mink played a key role in the enactment of Title IX of the Higher Education Act Amendments, which prohibited gender discrimination by federally-funded institutions. This legislation has been an important factor in ensuring equity for women in all educational programs, particularly school sports. Mink was concerned about a woman’s movement that focuses too much on middle-class white women. “The ‘glass ceiling’ is an upper-class glass ceiling for those aspiring to be bank presidents and executives, not those who can never rise above the minimum wage. The majority of people working at minimum-wage jobs in the United States are women. That’s the glass ceiling I am committed to doing something about.” [From Asian Americans Advancing Justice and Women of Hope: Asian Americans.] Learn more about Mink in the documentary Patsy Mink: Ahead of the Majority. Trailer: |

|

|

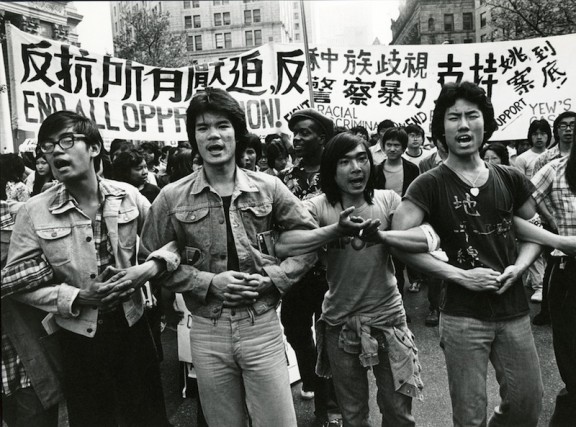

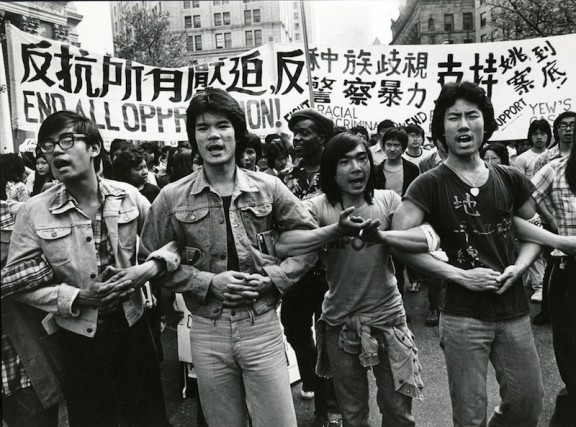

Peter Yew/Police Brutality Protests, 1975In April 1975, Peter Yew, a young Chinese-American living in New York City’s Chinatown, asked police to stop beating a 15-year-old whom they had stopped for a traffic violation. For his concern, Yew was savagely beaten right on the spot, taken back to the police station, stripped, beaten again and arrested on charges of resisting arrest and assault on a police officer. His beating was the last straw as 15,000 Chinatown community members took to the streets to fight back against police attacks and brutality against their community. Virtually every shop and factory in Chinatown was closed on May 19th for the demonstration and signs reading “Closed to Protest Police Brutality” were put in windows and on doors. The community united around demands for the dismissal of all charges against Yew, an end to discrimination of the Chinese community, and an end to discrimination in employment, housing, education, health, and all other social services for all minorities and working people. A week before the May 19th demo, several thousand people had marched on City Hall under an action sponsored by the Asian Americans for Equal Employment (AAFEE), raising demands similar to those raised at the May 19th action. The local business community and establishment refused to publicize or endorse the AAFEE action. A week later, the Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) called the May 19th action, bringing out old and young in one of the most united and militant actions ever taken by Chinatown residents. Although the CCBA tried to keep demands focused just on Peter Yew, the people of Chinatown clearly saw the broader issues, the fact that police repression was coming down in communities all across the U.S. This was shown by the slogans raised such as “Fight Police Brutality, Fight all Oppression!” When the cops attacked the march, the people responded immediately and fought back. As the police tried to drag off one of the demonstrators, others in the march jumped the cops and fought them tooth and nail. When two of the people were arrested and taken to the police station, the crowd surrounded the station and secured the release of their friends. [From Vietnam Veterans Against the War.] |

Ai-Jen PooWhen Poo started organizing domestic workers in 2000, many thought she was taking on an impossible task. Domestic workers were too dispersed, spread out over too many homes. Even Poo had described the world of domestic work as the “Wild West.” Poo’s first big breakthrough with the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) happened on July 1, 2010, when the New York state legislature passed the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. The bill legitimated domestic workers and gave them the same lawful rights as any other employee, such as vacation time and overtime pay. Though the bill was considered a major victory, the NDWA did not stop there, expanding operations to include 17 cities and 11 states. Read more about the NDWA here: www.domesticworkers.org. [Description from Americans Who Tell the Truth website.]

|

|

Jung Sai strikers. Image: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Library/UC Berkeley. |

Jung Sai Garment Workers Strike, 1974On July 15, 1974, workers at the Jung Sai factory (manufacturers of popular teen clothing brand Esprit de Corps) in San Francisco went on strike after Frankie Ma, a union activist, was fired for “unsatisfactory work.” Workers at Jung Sai endured appalling conditions: they earned $2 per hour and their work days often stretched to ten hours with few breaks, and no overtime pay. They had just voted in the union and saw this firing as an act of retaliation. The workers — most of them middle-aged Chinese immigrant women—protested the firing and unfair labor practices, and demanded better working conditions and the right to organize. This united body of immigrant workers inspired popular support from community, student, and working-class populations throughout the San Francisco Bay area. Their interaction with hundreds of Asian-American activists and supporters became an important turning point for Asian-American activism in the San Francisco Bay Area. The strike lasted six months and encouraged further immigrant activism, energizing a grassroots movement among Chinese immigrant workers facing similar unfair labor practices. After the plant closed down, claiming bankruptcy, the workers brought a suit before the National Relations Labor Board and won nearly 10 years later. [Adapted from The Asian American Movement, FoundSF.org, Rethinking the Asian American Movement, and “Union Women’s Alliance to Gain Equality (1971-1982).” |

|

Rinku Sen“I learned a lot about how human beings change, about the sense of worth that has to be activated in order for people to demand more out of society, and the sense of connection that has to be activated for people to stand up together and for each other.”Rinku Sen is the president and executive director of Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation, and the publisher of the award-winning news site Colorlines. As a racial justice activist and community organizer, Sen’s leadership at Race Forward has generated some of the most impactful racial justice successes, including the Drop the I-Word campaign aimed at media outlets to stop referring to immigrants as “illegal.” This resulted in the Associated Press, USA Today, L.A. Times, and many more dropping the i-word, affecting millions of readers every day. Born in India, her family moved to upstate New York when she was five. Some of Sen’s earliest recollections of life in India were tinged by race, Sen told NBC News. “One of my earliest memories was of being in the bath scrubbing myself when I was four-ish, trying to get as light as my cousin, whose mother is Dutch,” she said. Sen started her organizing career as a student activist at Brown University, fighting race, gender, and class discrimination on campuses. Majoring in Women’s Studies and receiving a Master’s degree in Journalism, Sen has written extensively about the race and gender dimensions of community organizing and is the author of Stir It Up: Lessons in Community Organizing and The Accidental American: Immigration and Citizenship in the Age of Globalization. [Adapted from Race Forward, NBC News, and Stir It Up.] Learn more about Sen and the work of Race Forward at raceforward.org. |

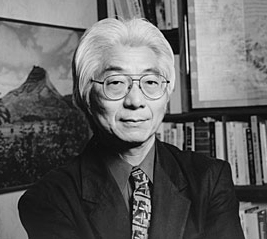

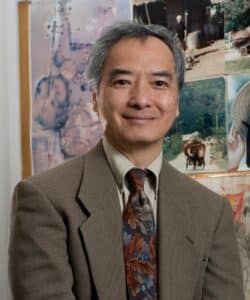

Ronald TakakiRonald Toshiyuki Takaki (April 12, 1939 – May 26, 2009) was the author and editor of more than 20 books, including Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (1989) and A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America (1993). Takaki established UC Berkeley‘s PhD program in ethnic studies, the first of its kind in the nation. “Ron Takaki elevated and popularized the study of America’s multiracial past and present like no other scholar, and in doing so had an indelible impact on a generation of students and researchers across the nation and world,” according to Don T. Nakanishi, director of UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center. Born in Honolulu on April 12, 1939, he was the grandson of a Japanese immigrant who went to Hawaii in 1886 to work in the sugar cane fields. After his father died, Takaki, who was seven, was raised by his mother and Chinese stepfather. He attended the College of Wooster in Ohio, where he was one of two Asian Americans on campus. This experience gave him a new awareness of himself as an ethnic American. Takaki recalled in a 2000 Lincoln Journal Star interview that one of his professors “asked me how long I’d been in this country, where did I learn to speak English. I told him I was from Hawaii and he says, ‘But how long have you been in this country?’ I guess I didn’t look American.” Takaki went on to earn a master’s degree in 1962, and a Ph.D. in history in 1967 from UC Berkeley, where he became drawn to campus activism, including the Free Speech Movement. “I was born intellectually and politically in Berkeley in the ’60s,” he told a San Francisco Chronicle reporter in 2003. In 1966, he was hired to teach UCLA’s first Black history course in the wake of the explosive Watts riots. When a student in the Black history class asked him which revolutionary tools he could teach them, Takaki replied: “We’re going to study the history of the U.S. as it relates to African Americans. We’re going to strengthen our critical thinking skills and our writing skills. These can be revolutionary tools if we make them so.” In 1971, Takaki returned to UC Berkeley as the Department of Ethnic Studies’ first full-time teacher. He became wildly popular, filling auditoriums with hundreds of students hungry for perspectives on the struggles of America’s minority groups. Takaki served as chair of ethnic studies from 1975-77, and in the mid-1980s established at UC Berkeley the nation’s first doctorate program in ethnic studies. He then turned his attention to ensuring that each student satisfy an American Cultures requirement to graduate. He was a vigorous proponent of multicultural education and a vocal opponent of Proposition 209, the 1996 California ballot initiative that rolled back affirmative action policies in state-funded institutions. [From Los Angeles Times and UC Berkeley News.] Learn more about Ronald Takaki. |

|

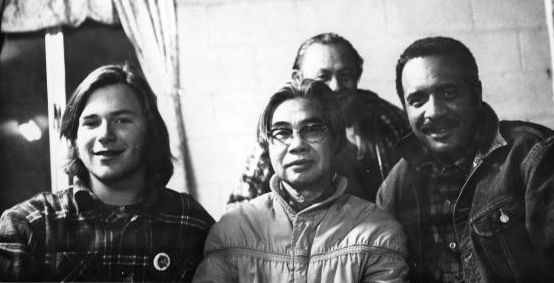

Philip Vera Cruz (center), Vice President of the United Farm Workers (UFW), and unidentified men at a boycott meeting, 1970s. Image: Richard Grady/Walter P. Reuther Library. |

Philip Vera Cruz‘The movement should be the most important thing. … The movement must go beyond its leaders.”Philip Vera Cruz (December 25, 1904 – June 12, 1994), a Filipino immigrant, worked in the midwest then moved to California in 1943 becoming a farm worker. He joined the Agricultural Worker Organizing Committee (AWOC) and soon became a leader in farm worker’s rights. In 1965, he was an active force in the AWOC decision to strike against grape growers in Delano, California. The strike and boycott soon won the support of Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers of America, and led to the eventual merging of the two groups to form the United Farm Workers. Vera Cruz was elected a vice president of the union, a position he held until he left the union in protest in 1977. Cruz also formed the Farm Workers Credit Union and created Agbayani Village, a retirement community for older farm workers. Throughout his career Vera Cruz worked for migrant and farm worker rights, and was active in the Asian American, especially Filipino, rights movement and community. Vera Cruz once wrote, “Leadership, I feel, is only incidental to the movement. The movement should be the most important thing. If the leader becomes the most important part of the movement, then you don’t have a movement after the leader is gone. The movement must go beyond its leaders. It must be something that is continuous, with goals and ideals that the leadership can build on.” [Adapted from the Walter P. Ruether Library biography.] Watch this remembrance clip from Asian Americans Advancing Justice: AAPI Civil Rights Heroes – Philip Vera Cruz from Advancing Justice – ALC on Vimeo.

|

|

|

Ngo Vinh LongNgo Vinh Long (April 10, 1944 – October 12, 2022) was a Vietnamese American historian, lifelong activist, and author of the 1973 book Before the Revolution: The Vietnamese Peasants Under the French. Born in the Mekong Delta, he fought U.S. involvement in Vietnam at an early age. He emigrated from Vietnam in 1964 to attend Harvard University, where he studied under Henry Kissinger and Samuel Huntington. Vinh Long helped create the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars and the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (now Critical Asian Studies) in the late 1960s, and was a professor of history at the University of Maine from 1985 to 2022. |

Source: Online Archive of California |

Yick Wo v. HopkinsOn May 10, 1886, Lee Yick won a Supreme Court case that ensured that all people —citizens and non-citizens — had equal protection under the law. Lee Yick and Wo Lee, Chinese immigrants, ran laundries in San Francisco. In 1880, San Francisco passed a law requiring a permit for laundries housed in wooden buildings as they were more vulnerable to fires. Of the 320 laundries in San Francisco, 310 were in wooden buildings, and most of them — 240 — were owned by Chinese persons. Not one Chinese laundry applicant was issued a permit. When Sheriff Hopkins tried to arrest Yick and Lee for not having a permit, they refused to pay the $10 fine, and were jailed. Each sued, arguing that the fine and discriminatory enforcement of the ordinance violated their rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Their cases, compiled under the name Yick Wo v. Hopkins, was argued at the Supreme Court in 1886 (Yick Wo was the name of the laundry that Lee Yick ran). In an unanimous opinion authored by Justice T. Stanley Matthews, the court concluded that, despite the impartial wording of the law, its biased enforcement violated the Equal Protection Clause. According to the court, even if the law is impartial on its face, “if it is applied and administered by public authority with an evil eye and an unequal hand.” The kind of biased enforcement experienced by the plaintiffs, the court concluded, amounted to “a practical denial by the state of that equal protection of the law” and therefore violated the provision of the 14th Amendment. [Adapted from PBS’s “The Strange Case of the Chinese Laundry,” and Oyez.org.] |

|

Merle WooIn 1982, Merle Woo challenged UC Berkeley after being fired from her job as a lecturer in Asian American Studies/Ethnic Studies (AAS). Woo, a member of the Freedom Socialist Party, Radical Women, an open lesbian, and a renowned poet, was fired after criticizing the increasing conservatism of tenure-track faculty in UC’s Asian American Studies Department. Her 1982 federal and state lawsuits charged the university with discrimination based on race, sex, political ideology, and sexual orientation. As Woo explained in a news release, “They fired me because I was visible. I took my protected free speech rights seriously, spoke out against the imminent death of Ethnic Studies, spoke out about who I am, totally and fully and with dignity.” Woo’s supporters included Angela Davis, Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, Barbara Smith, Congressman Ron Dellums, Gloria Steinem, and Mitsuye Yamada. Woo won the free speech/multi-discrimination case against UC Berkeley and was reinstated in 1984, only to be fired again in 1986. In 1989, she won a union arbitration against UC Berkeley. [Adapted from Proud Heritage: People, Issues, and Documents of the LGBT Experience, Freedom Socialist: Voice of Revolutionary Feminism, and The Merle Woo Project Prize.]

|

|

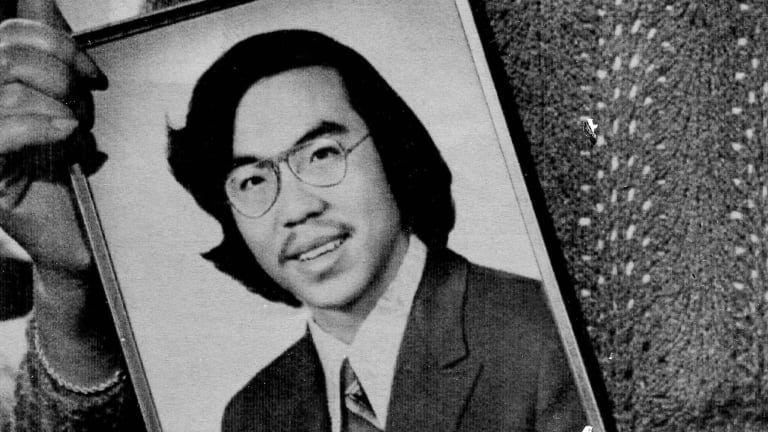

Helen ZiaA feminist and antiwar activist during the Vietnam War, Helen Zia is now an author, an outspoken proponent of LGBTQ rights, and a former journalist. Zia cofounded American Citizens for Justice following her coverage of the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit. As described on her website, The daughter of immigrants from China, Helen has been outspoken on issues ranging from human rights and peace to women’s rights and countering hate violence and homophobia. She is featured in the Academy Award-nominated documentary, Who Killed Vincent Chin? and was profiled in Bill Moyers’ PBS series, Becoming American: The Chinese Experience. In 2008 Helen was a Torchbearer in San Francisco for the Beijing Olympics amid great controversy; in 2010, she was a witness in the federal marriage equality case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. |

Find more resources for the classroom and key events in history below.

Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066

Thank you. This is a valuable resource.