By Bill Bigelow

By Bill Bigelow

Here’s a history quiz to use with people you run into today: Ask them who ended slavery.

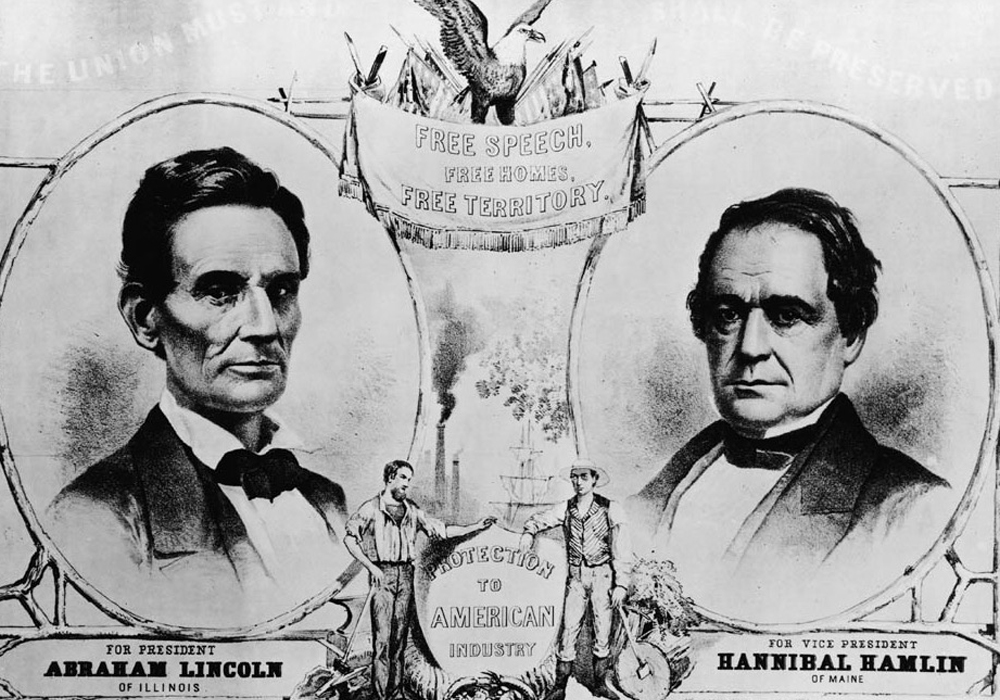

I taught high school U.S. history for almost 30 years, and as we began our study, students knew the obvious answer: Abraham Lincoln. But by the time our study ended, several weeks later, their “Who ended slavery?” essays were more diverse, more complex — and more accurate. In coming months and years, teachers’ jobs will be made harder by Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln, in which Daniel Day-Lewis gives a brilliant performance as, well, Lincoln-the-abolitionist. The only problem is that Lincoln was not an abolitionist.

Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner chose to concentrate on the final months of Lincoln’s life, when, as the film shows in compelling fashion, the president went all-out to pass the 13th Amendment, forever ending U.S. slavery. Missing from this portrait is the early Lincoln — the Lincoln that did everything possible to preserve slavery.

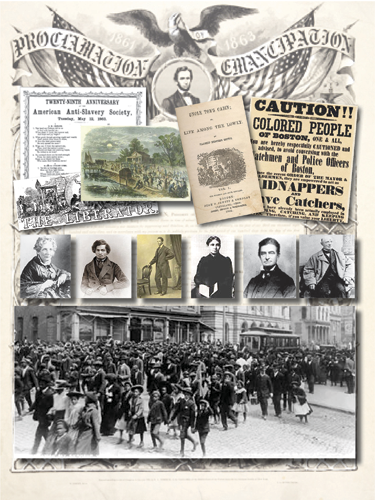

Today’s Common Core State Standards propose that teachers concentrate on the compact and stirring Gettysburg Address, also featured in Lincoln. But my students and I begin with Lincoln’s first words as president, his first inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1861. In this speech, not quoted in a single commercial textbook I’ve ever seen, Lincoln promised slaveowners that they could keep their slaves forever. He said that “ample evidence” existed in all his published speeches that he had no intention of ending slavery, and quoted himself to that effect: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” And, in less explicit, but no less clear language, Lincoln promised to “cheerfully,” as he put it, enforce the Fugitive Slave Act in protection of the nation’s “property, peace, and security.” Finally, in a gesture rich with irony, Lincoln said that he would not oppose the constitutional amendment that had recently passed Congress, “to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service.” Had it gone into effect, this slavery-forever amendment would have been the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

According to historian Eric Foner in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book on Lincoln and slavery, The Fiery Trial, Lincoln:

- sent that pro-slavery 13th Amendment to the states for ratification;

- agreed to admit New Mexico to the Union as a slave state;

- continued with schemes to deport — “colonize” in the jargon of the day — African Americans, proposing they be sent to Guatemala, Chiriqui (Colombia), and Haiti;

- and in just the first three months after the Civil War began, returned more escaped slaves to their supposed owners than had been returned in the entire presidency of his immediate predecessor, James Buchanan.

As the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the The Liberator, commented in late 1861, Abraham Lincoln “has evidently not a drop of anti-slavery blood in his veins.”

Lincoln may be remembered today as “the Great Emancipator,” but Lincoln was no abolitionist. His aim throughout his presidency was to keep the Union together, a task fraught with contradictions, as large swaths of the country embraced both the Union and slavery — for example, Missouri, Delaware, Maryland, and Kentucky. As Lincoln himself said famously in August 1862, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union.”

Lincoln’s stance on slavery as the war progressed was based on military rather than moral considerations.

And that’s the necessary context for students to approach the Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect 150 years ago, on January 1, 1863. Interestingly, despite the fact that the proclamation is mentioned in virtually every textbook, it is never printed in its entirety. Perhaps that’s because despite its lofty-sounding title, this is no stirring document of liberty and equality; in fact, it does not even criticize slavery. “Emancipation” is presented purely as a measure of military necessity. Lincoln offered freedom to enslaved people in those areas only “in rebellion against the United States.” It reads like a document written by a lawyer — one who happened to be a Commander in Chief — not an abolitionist. It even goes county by county listing areas where slavery would remain in force, “precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.” According to Eric Foner, the proclamation left more than 20 percent of enslaved people still in slavery — 800,000 out of 3.9 million.

Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution features primary documents, essays and questions to teach the untold story of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

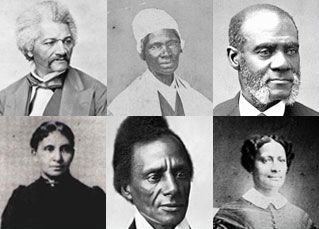

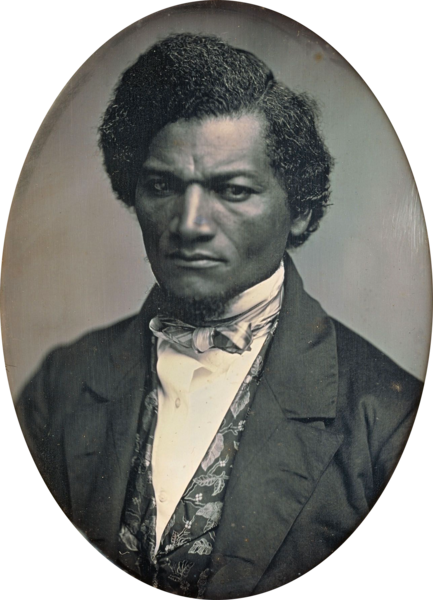

No doubt, the Emancipation Proclamation was a huge deal, and it was cheered by abolitionists and even those who remained enslaved. As the great African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass pointed out, Lincoln’s proclamation united “the cause of the slaves and the cause of the country.” Those opposed to slavery were determined to use the Emancipation Proclamation as an instrument to end slavery everywhere and forever — regardless of Lincoln’s more limited intent. Freedom would be won, not given.

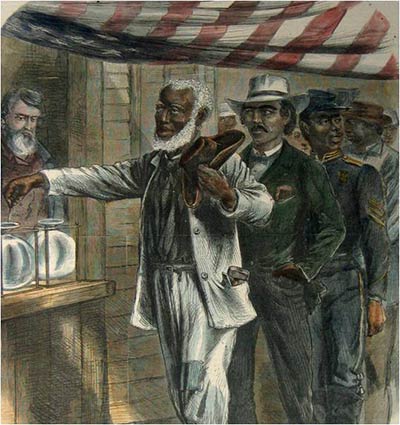

With rare exceptions — like the American Social History Project’s fine Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution — middle and high school textbooks fail to credit the real anti-slavery heroes in this story: the enslaved themselves, along with their black and white abolitionist allies. While early in the conflict Lincoln was offering verbal cake and ice cream to slaveowners, the enslaved were doing everything they could to turn a war for national unity into a war to end slavery, impressing Union generals with their courage, skill, and knowledge — ultimately forcing Lincoln to reverse his early policy of returning those fleeing slavery and, in time, leading the president to embrace their entry into the war as soldiers. The actions of the formerly enslaved even turned some white Union soldiers into abolitionists.

This resistance to slavery, along with its effects on Union soldiers, is captured in this 1862 testimony from General Daniel E. Sickles, quoted in Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution:

The most valuable and reliable information of the enemy’s movements in our vicinity that we have been able to get derived from Negroes who came into our lines . . .

They will submit to any privation, perform any duty, incur any danger. I know an instance in which four of them recently carried a boat from the Rappanhannock River [in Virginia], passing through the enemy’s pickets successfully, to the Potomac and crossed over to my camp and reported themselves there. They gave us information of the enemy’s force which was communicated to headquarters; a service upon which it would be difficult to fix a price. These services rendered by these men are known to the soldiers, and contribute, I presume, largely to the sympathy they feel for them . . .

There was one case in the 5th regiment where a man named Cox claimed some slaves. He was very badly treated by the soldiers. He came there with an order from the division headquarters for two or three slaves. He pointed out who they were and undertook to take them away; but the soldiers pounced upon him and beat him severely. . . . He went away without his slaves.

Who we “credit” for the end of slavery in the United States has important contemporary implications. As Lonnie Bunch, director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, points out in the film Monumental Myths, if it appears that Abraham Lincoln gave blacks their freedom, then “you create an environment where people begin to think, ‘Well, African Americans have always had things handed to them.’ It gets carried into the notions of welfare and the like” — African Americans as receivers of gifts from generous white people.

Beginning with the notion that “Columbus discovered America,” this top-down, Great Man approach has long characterized history instruction in our country. Things happen — good or bad — because those in power make them happen. What this misses is, through our compliance or resistance, the actions of ordinary people. And when it comes to momentous social changes, like the abolition of slavery, one will always find social movements and the oppressed themselves at the center. As historian Howard Zinn said about the end of slavery: “Blacks won their freedom because for 30 years before the Civil War, they participated in a great movement of resistance.”

So when I ask my students to write an essay on “Who (or what) ended slavery?” I get lots of different answers. But none of them credits a single individual. And all of them include evidence of how, in myriad ways, the people themselves make history.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Posted on: Huffington Post | Common Dreams.

© 2012 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn