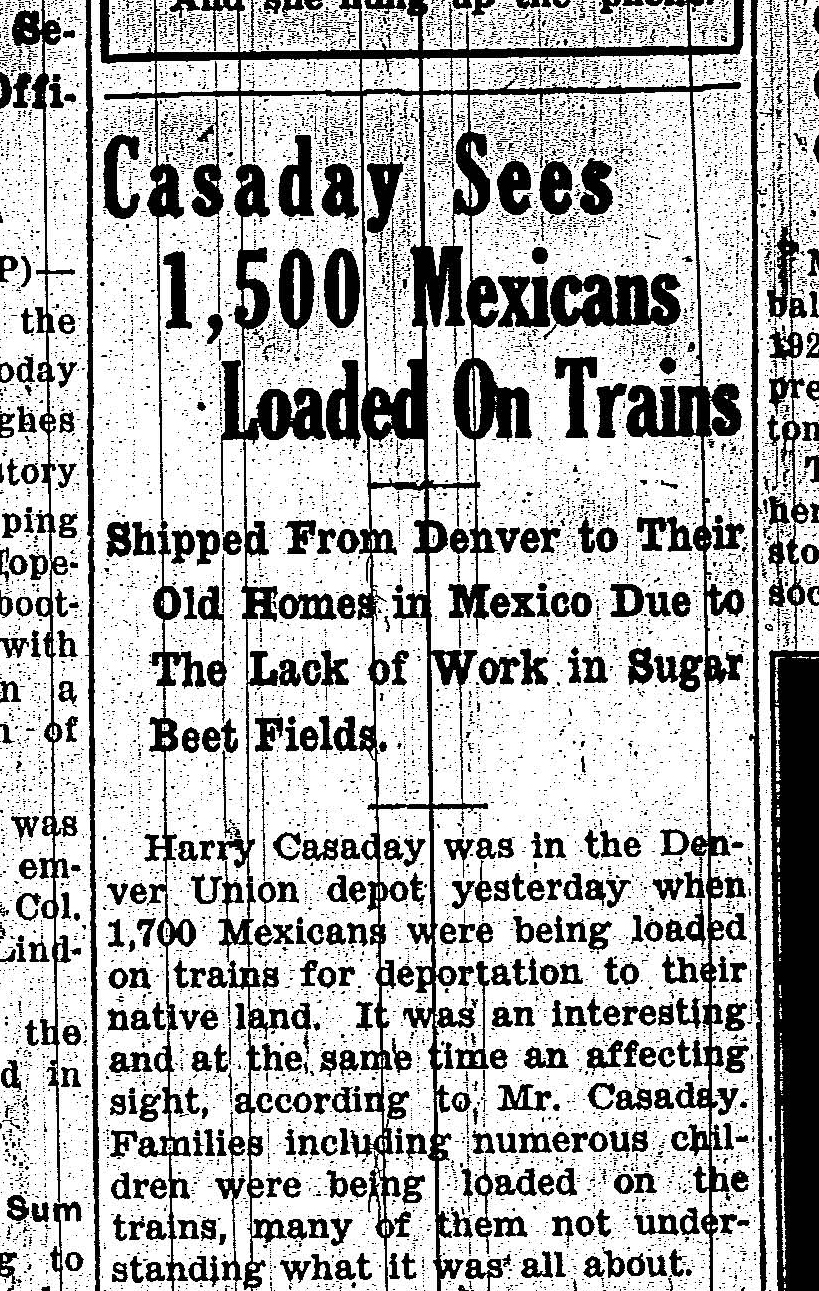

A Boulder, Colorado, newspaper reports on the deportations of unemployed sugar beet workers. Source: Boulder County Latino History Project

By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

The Trump Administration’s horrifying record on immigration, exemplified by the heartbreaking scenes of family separation during the summer of 2018, sparked a new round of discussion and debate about U.S. deportation policy. Of course, deportations are nothing new; Obama was rightly criticized as the Deporter-in-Chief. But with enthusiastic cruelty and vigor, the Trump administration has embraced deportation, including the targeting of long-term residents with no criminal record. As acting Director of ICE, Thomas Homan explained, “The president made it clear in his executive orders: There’s no population off the table. If you’re in this country illegally, we’re looking for you and we’re going to look to apprehend you.” The massive reach of this effort, the uncertainty and terror it elicits, and the opacity of the controlling laws, make this a dangerous moment, not just for immigrants and their families, but for everyone who cares about due process and human rights. It also recalls an earlier time in U.S. history, nearly 90 years ago, when Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants were ousted from the country in enormous numbers.

For me, teaching in the time of Trump meant I wanted to design an immigration unit for my high school U.S. history class to help students both make sense of this dangerous moment and, hopefully, think about how to fight back. I wrote a trial role play on the deportations of the 1930s to act as both a warning and a guide.

In this, I was heeding the call of a group of 4th/5th graders in California who, in 2015, successfully lobbied their legislators to require that the story of the deportations be told in classrooms. Such legislative action was needed because this mass deportation of as many as 1.8 million people rarely makes it into the standard curriculum or textbooks. This omission is symptomatic of the diseases plaguing textbooks in general: their whitewashing of history, amplification of presidents over people, unswerving commitment to a narrative of progress, and marginalization of people of color to sidebars and extension activities.

Take my textbook, Pearson’s American Journey. It has one paragraph on “Hispanic Americans” during the Great Depression. Of the six-sentence paragraph, only two sentences address the deportations. They read:

Economic woes and racism drove nearly half a million Mexican immigrants and their American-born children from the United States in the 1930s. Local authorities in the Southwest encouraged the federal government to deport Mexicans and offered free transportation to Mexico.

Notice the disembodied “economic woes” and “racism” that did the dirty work of driving people from their homes. Notice the “Mexican immigrants and their American-born children,” obscuring the fact that 60 percent of those deported were citizens, children and adults. And finally, most perplexing, notice the textbook’s cliffhanger, never telling readers what actually happened. Local folks “encouraged” the federal government to act, but did it? What happened?

What happened is that men, women, and children — immigrant and U.S.-born, citizen and noncitizen, long-time residents and temporary workers — all became the targets of a massive campaign of forced relocation, based solely on their perceived status as “Mexican.” They were rounded up in parks, at work sites, and in hospitals, betrayed by local relief agencies who reported anyone with a “Mexican sounding” name to the Immigration Service, pressured (and often tricked) into “voluntary” deportation — sometimes called repatriation — by municipal and state officials, and forcibly deported in trains and buses, to a country some hadn’t lived in for decades and others never at all.

Some families relocated “voluntarily,” driven out by joblessness, harassment, and nativist fear-mongering, rather than the Immigration Service. By Dorothea Lange. Source: Library of Congress

American Journey and other textbooks ignore the stories of loss and forced relocation behind the numbers, stories like the terrifying raid that took place at La Placita park in Los Angeles in 1931. The park was a vibrant cultural hub in an immigrant neighborhood, a place to listen to music, talk politics, socialize. According to historian Doug Monroy, “In the days before television and radio, if you wanted stimulation and excitement, you went to La Placita.” On a sunny afternoon in late February, the park was full of close to 400 people when suddenly, immigration agents sealed off the exits. Some were in military olive uniforms, others in plain clothes, wielding guns and batons. The agents demanded everyone in the park line up and show their papers. They arrested dozens and deported many. But the greatest impact was psychological, instilling terror into the Mexican American community.

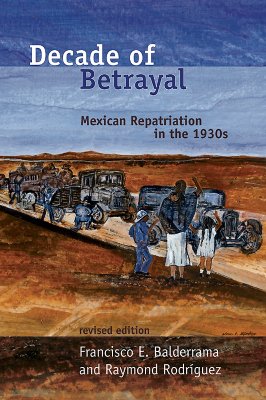

The United States’ own investigation of the deportations declared them unconstitutional. The federally appointed Wickersham Commission stated in its 1932 report: “The apprehension and examination of supposed aliens are often characterized by methods [that are] unconstitutional, tyrannic, and oppressive.” The Wickersham Commission may have been thinking about cases like that of Angela Hernández de Sánchez. As recounted in the book, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s, by Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, Sánchez was returning from a short trip visiting relatives in Mexico, something she had done dozens of times before, when she was arrested and subjected to intrusive venereal disease tests. Since Sánchez had been a continuous resident of the United States since 1916, she was not eligible for deportation under current law. But even with her proof of residence and her negative blood test for sexually transmitted diseases she and her U.S.-born children were deported.

Another textbook used in my school’s Advanced Placement classes, America: A Concise History (Bedford/St. Martins), attributes many of the departures of Mexican Americans to voluntary action, telling students that “many Mexican farm laborers left voluntarily as the depression deepened.” But surely families fleeing persecution cannot be accurately described as volunteers. Perhaps if America devoted more than a single paragraph to this history, there might be space to tell the story of the family of one of the authors of Decade of Betrayal, Raymond Rodríguez. Rodríguez says his father — a legal resident — decided to leave following the La Placita raid, concluding the United States was too dangerous for him and his family. But his wife refused to leave with their five U.S.-born children. Rodríguez recalls his father’s last words to her were, “If you don’t go [too] . . . you’ll starve to death and maybe worse.” The family never saw him again.

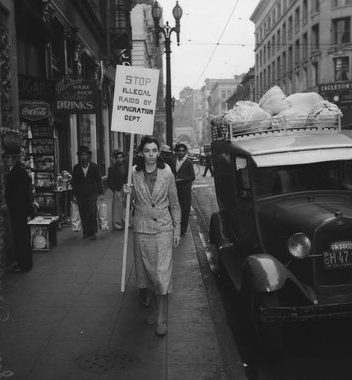

Woman holding a sign that says “STOP ILLEGAL RAIDS BY IMMIGRATION DEPT.”

As is clear from the story of the Rodríguez family, those targeted by nativism and deportations did not simply acquiesce to their treatment. Community organizations like Cruz Azul Mexicana and La Sociedad de Madres Mexicanas in Texas helped finance relief and legal services. El Confederacion de Sociedades Mexicanas in Los Angeles called “repatriation” a racist plot to remove all Mexican Americans, a sentiment reinforced by the Mexican press and radio, working on both sides of the border. Newspapers like La Opinión and La Prensa provided an important counternarrative of the deportations to the racist framing of The New York Times and The Saturday Evening Post. And leaving itself was sometimes an act of resistance. As one girl from Indiana explained, “This is my country but after the way we have been treated I hope never to see it again. . . As long as my father was working and spending his money in Gary stores, paying taxes and supporting us, it was all right, but now we have found we can’t get justice here.”

The sheer complexity of this history may partially explain why textbooks get it so wrong. Unlike other nativist efforts of the early 19th century, these deportations were not driven by any signature piece of legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 or the Immigration Act of 1924. Rather they were orchestrated using a patchwork of federal and local authority, existing but seldom used deportation rules, and simple mob action against a vulnerable population. But it is precisely this messiness that is fruitful to surface with students. If no single law or leader ordered these deportations, then why and how did they happen and who is responsible for the damage they wrought? This is the question I raise in the Deportations on Trial lesson.

According to photographer Dorothea Lange, this mother told her, “Sometimes I tell my children that I would like to go to Mexico, but they tell me ‘We don’t want to go, we belong here.'” Source: Library of Congress

This is not just an academic exercise. Understanding the complex causes of illegal deportations in the 1930s can alert students to similar dynamics today. Just as students see that no single actor was responsible for the deportations of the 1930s, they can recognize that President Trump alone does not have the power to terrorize immigrants and their families. For that it takes the collaboration of the corporate media, ICE agents, for-profit detention centers, wall-builders and contractors, and an electorate primed by racism and capitalism to misplace blame for their own low wages or precarious social position. If that is true, then it matters how every single one of us responds.

I want my students to take what they have learned about deportations of the 1930s and be like Jordon Dyrdahl-Roberts, the Montana Department of Labor worker who quit his job, explaining, “There were going to be ICE subpoenas for information that would end up being used to hunt down & deport undocumented workers. I refuse to aid in the breaking up of families. I refuse to just ‘follow orders.’” I want my students to be like the more than 100 public defenders who walked off the job in New York City to protest ICE arrests in courthouses or like members of the Sanctuary Movement who are devising novel and brave ways to put themselves between ICE agents and their targets. And I want my students to be like those 5th graders in California who demanded they be taught about the deportations of the 1930s, who insisted that history matters, and that it might be the history that is not in the textbooks that matters the most.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series. © 2018 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series. © 2018 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn