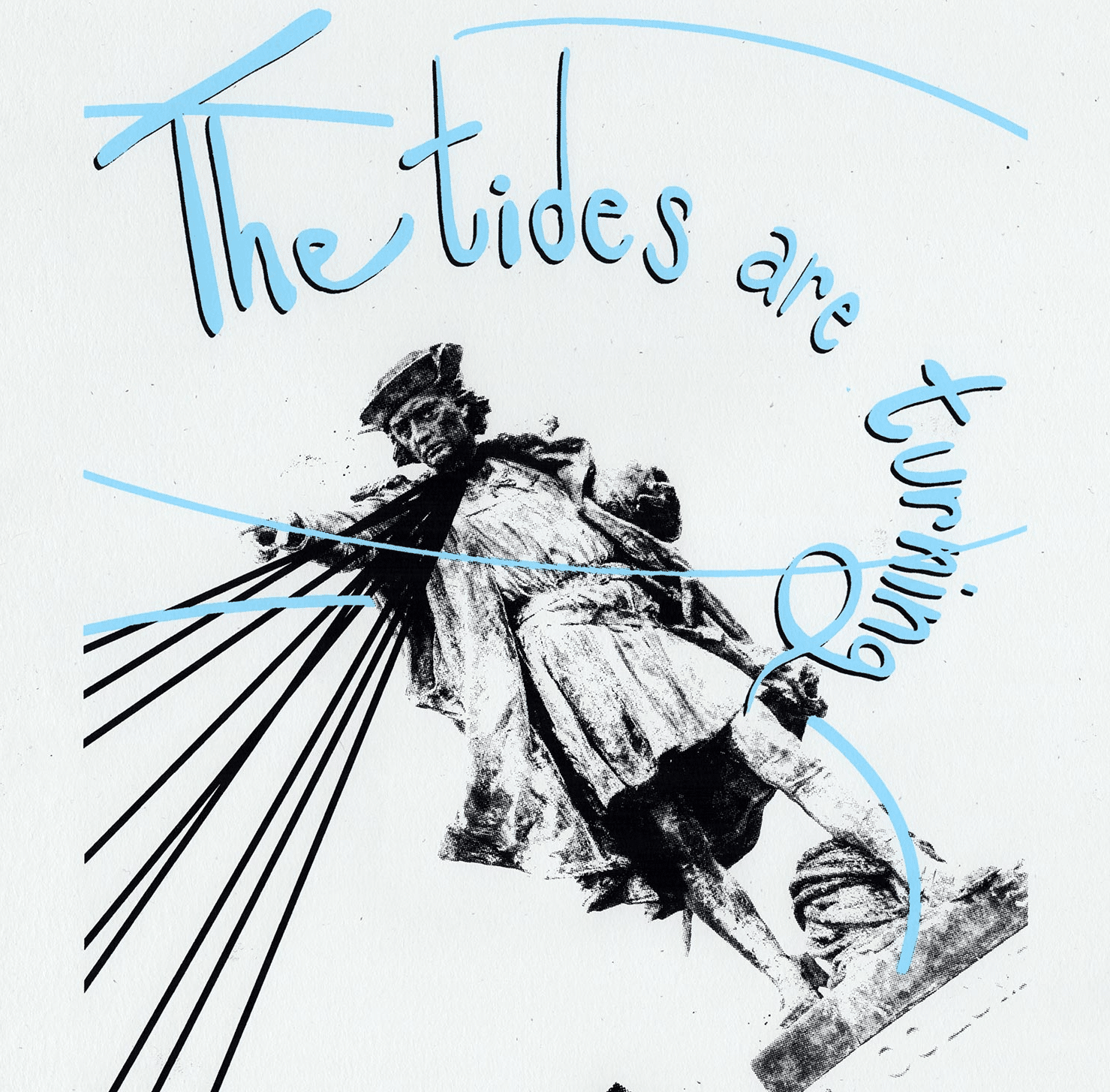

A group of about 50 people met at the Minnesota Capitol to call for the Christopher Columbus statue to be taken down. Source: Pioneer Press/Scott Takushi.

By Bill Bigelow

A New York Times article, following the white supremacist demonstrations in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the murder of anti-racist activist Heather Heyer, described the growing calls to remove monuments that celebrate the Confederacy. The article went on to cite some who balk, however, when “the symbolism is far murkier, like Christopher Columbus.”

But there is nothing murky about Columbus’ legacy of slavery and terrorism in the Americas. The record is clear and overwhelming. The fact that The New York Times could report this with such confidence — adding that “most Americans learn rather innocently, in 1492 [Columbus] sailed the ocean blue until he discovered the New World” — means that educators and activists still have much work to do.

In fact, Christopher Columbus launched the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1494, when he sent back at least two dozen enslaved Taínos, including children, to Spain. In February of that year, Columbus dispatched 12 of his 17 ships from the Caribbean back to Spain with a letter to be delivered to the king and queen by Antonio de Torres, captain of the returning fleet. Columbus wrote:

There are being sent in these ships some Cannibals, men and women, boys and girls, which Your Highnesses can order placed in charge of persons from whom they may be able better to learn the language while being employed in forms of service, gradually ordering that greater care be given them than to other slaves.

Here, as in so much of world history, violence and exploitation is sprinkled with a perfume of benevolence. Later in the letter, Columbus explains to the king and queen that his plans for colonizing the lands he has “discovered” could be financed by slavery:

These things could be paid for in slaves taken from among these cannibals, who are so wild and well built and with a good understanding of things that we think they will be finer than any other slaves once they are freed from their inhumanity, which they will lose as soon as they leave their own lands.

A year later, in February 1495, Columbus initiated massive slave raids, ordering his men to round up 1,600 Taínos and to bring the captives to La Isabela, on the island of Hispaniola (today’s Haiti and the Dominican Republic), where the “best” 500 (some accounts say 550) men and women could be shipped to Spain. One of the colonists, Michele de Cuneo, was an eyewitness to these crimes. “Of the rest who were left,” wrote Cuneo, “the announcement went around that whoever wanted them could take as many as he pleased; and this was done.”

It’s worth pausing to reflect on the terror the Taínos must have experienced being torn from home and families, and packed on ships bound for an uncertain destination — that is, those who survived Columbus’ slavery free-for-all. Where are the monuments to these first victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade?

Gold. That was the essence of Columbus’ “enterprise” — la empresa — as he called it. Wrote Columbus: “Gold is a wonderful thing! Whoever owns it is lord of all he wants. With gold it is even possible to open for souls the way to paradise.” Later in 1495, to effect this gold lust, Columbus initiated the policy of forcing Taínos throughout Hispaniola to deliver tributes of gold every three months.

The Taínos resisted, of course, but were brutally suppressed by the Columbus regime. The Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas wrote that to quell the resistance, Columbus ordered his men to “spread terror among the Indians to show them how strong and powerful the Christians were.” In sickening detail, Las Casas described some of what it meant for the Spaniards to “spread terror” among the Taínos:

Once the Indians were in the woods, the next step was to form squadrons and pursue them, and whenever the Spaniards found them, they pitilessly slaughtered everyone like sheep in a corral. It was a general rule among Spaniards to be cruel; not just cruel, but extraordinarily cruel so that harsh and bitter treatment would prevent Indians as daring to think of themselves as human beings or having a minute to think at all. So they would cut an Indian’s hands and leave them dangling by a shred of skin and they would send him on saying, “Go now, spread the news to your chiefs.” They would test their swords and their manly strength on captured Indians and place bets on the slicing off of heads or the cutting of bodies in half with one blow. They burned or hanged captured chiefs.

No, there is nothing murky about Columbus’ record of cruelty in the Caribbean. One can read the horrific details even in the biography of Columbus written by his own son Ferdinand. What’s murky are any remaining rationales for failing to topple monuments to this brutal exploitation of Indigenous peoples in the Americas, for keeping the Columbus Day holiday, or for failing to address a curriculum that, as The New York Times describes, allows children to learn that Columbus “sailed the ocean blue until he discovered the New World.”

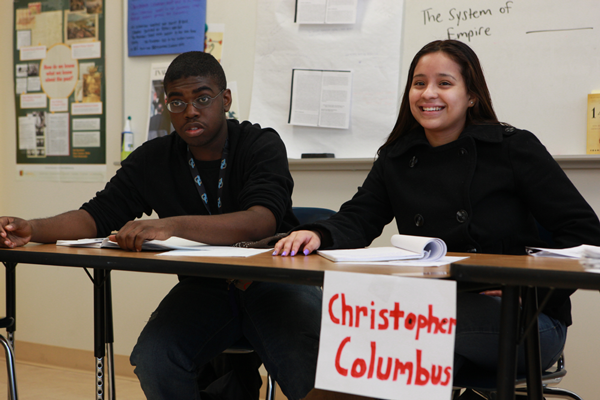

Students engaged in “The People vs. Columbus et al.” role play.

Twenty-five years ago, I wrote an article, “Once Upon a Genocide,” reviewing the major children’s literature about Columbus. My conclusion was that these books teach young readers that colonialism and racism are normal. Consistently, the books presented Columbus coming ashore on the lands he “discovered,” planting a flag, claiming it in the name of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, and naming the island San Salvador — erasing the rights and humanity of the original inhabitants. No book I reviewed at that time asked children to reflect on who or what gave Columbus the authority to take over other people’s land. These picture books were literary monuments to white European domination, and to the subordination of non-white Others.

Through my work as curriculum editor with Rethinking Schools magazine, I have been in a number of elementary and middle schools over the past couple of years. Sadly, many of the same books I reviewed in the early 1990s still populate school libraries. The good news is that, these days, many more teachers approach the Columbus invasion from the standpoint of the Taínos. One needn’t tell young children about people’s hands being chopped off for them to realize that it is wrong for people to arrive at your home from far away, claim it as theirs, and demand you work for them.

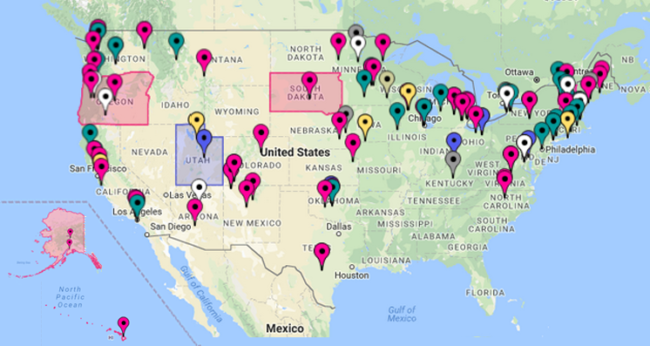

In classrooms throughout the country, students are putting Columbus on trial — along with the system of empire that animated his voyages. Instead of reading children’s books and textbooks uncritically, teachers are asking students to read for the silences: What important information is missing, whose stories are not being told, whose lives are absent? In some schools, students are writing new children’s books that tell a fuller, more accurate history of Columbus’ arrival and the people who were here first. (Many of these activities are described at the Zinn Education Project, and in the book I co-edited, Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years.)

And throughout the country, schools, school districts, and cities — including Berkeley, Seattle, Portland, Denver, Albuquerque, and, most recently, Los Angeles — have abandoned Columbus Day in favor of Indigenous Peoples Day.

Donald Trump may still — for the moment — be president, but he is not president of how we remember the past. Everywhere people of conscience are challenging the iconography of exploitation, racism, and colonial domination. Slowly, we are toppling Confederate monuments — and others celebrating more contemporary scoundrels like Philadelphia’s Frank Rizzo.

When I lead workshops for educators critiquing how the traditional children’s literature on Columbus celebrates white lives at the expense of people of color, how this literature endorses the bullying of little nations by big nations, how it teaches that there are two kinds of people in the world, the worthy and the unworthy, I end by asking participants: Why? Why is it that for such a long period of time these books have told a consistent story — is there some publisher conspiracy to lie to children?

No doubt there are many possible explanations. But the one I find most compelling is that in fundamental ways, Columbus’ world is not so different from the world we live in today. Big countries continue to dominate “lesser” nations. The quest for profit is still paramount. The world is still sliced in two between the worthy — the owning classes, the corporate masters, the generals — and those the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano called los nadies — the nobodies. The invaded, the owned, the bombed, the poisoned, the silenced.

So yes, let’s pull down the monuments, let’s make the holidays more inclusive, let’s rewrite the textbooks and children’s literature. But let’s also challenge the fundamental structures of ownership, power, and privilege that have given us such a skewed constellation of heroes and holidays.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Published on: Huffington Post | Common Dreams | AlterNet.

© 2017 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn