Scholastic and the coal industry ended their partnership when it got widespread media exposure.

By Bill McKibben and Bill Bigelow

Maybe you’ve heard. We are facing a climate crisis that threatens life on our planet. Climate scientists are unequivocal: we are changing the world in deep, measurable, dangerous ways — and the pace of this change will accelerate dramatically in the decades to come.

Then again, if you’ve been a middle school or high school student recently, you may not know this.

That’s because the gap between our climate emergency and the attention paid to climate change in the school curriculum is immense. Individual teachers around the country are doing outstanding work, but the educational establishment is not. Look at our textbooks. The widely used Pearson/Prentice Hall text, Physical Science: Concepts in Action, waits until page 782 to tell high school students about climate change, but then only in four oh-by-the-way paragraphs. A photo of a bustling city includes the caption: “Carbon dioxide emissions from motor vehicles, power plants, and other sources may contribute to global warming.” Or they may not, the book seems to suggest.

IAT’s Coordinated Science: Physical, Earth and Space Science devotes several pages late in the book to climate change, and concludes with this doubt-soaked passage: “Some people take the position that the increase in carbon dioxide should be reversed. They believe this is necessary even though the size of the contribution to global warming is not certain. It is their belief that the consequences would be very difficult to handle. Other people take a different position. They consider that it would be unwise to disrupt the world’s present economy. They consider the future danger to be questionable. The big problem is that no one is certain that rapid global warming will take place. If it does, it may be too late to do anything about it!”

The danger of climate change as “questionable”? ExxonMobil itself could not have produced a more skeptical approach.

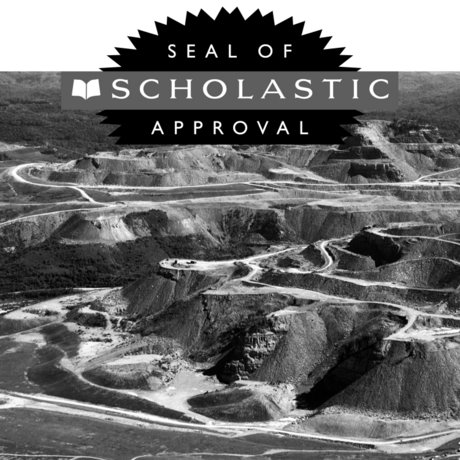

These textbooks are not mere egregious outliers; they are typical of commercially produced science and social studies teaching materials. In fact, a partnership between the American Coal Foundation and Scholastic to create a propagandistic 4th grade curriculum was ended only last year, when educators and environmentalists exposed the lessons’ absurd pro-industry biases. Scholastic’s curriculum, The United States of Energy, was distributed free to tens of thousands of elementary teachers. It showed gleaming piles of coal, along with many of its alleged benefits. Students didn’t learn of a single problem, including coal’s huge contribution climate change.

But as state legislatures get into the business of writing school curricula, things may go from awful to worse. Take Tennessee. It just became the fourth state — following Louisiana, Texas, and South Dakota — to pass a law that requires global warming to be taught as one of a number of “scientific controversies.”

The fact that Tennessee is home of the infamous 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial makes the new law ironic, but not funny. As the American Association for the Advancement of Science explains, “asserting that there are significant scientific controversies about the overall nature of these concepts when there are none will only confuse students, not enlighten them.”

Mountaintop removal in Martin County, Kentucky. Source: Wikimedia Commons/www.mountainroadshow.com.

If you happen to be a member of the one percent that owns a coal company, oil wells, or a pipeline, young people’s confusion is a good thing. For the rest of humanity, the passivity generated by this confusion is tragic.

Of course, educators cannot simply blame the lack of climate education on greedy corporations and the legislators they buy. In high schools, too often teachers regard the walls between disciplines as fixed and legitimate. Most social studies teachers thus far seem willing to leave discussion of carbon dioxide, the mechanics of the greenhouse effect, and “feedback loops” to the science department. And science teachers, overwhelmed by the requirements of their own discipline, are reluctant to trespass into the social causes and consequences of climate change. Teachers of other disciplines — drama, language arts, math — may wonder about the relevance of the climate for their subjects. And elementary teachers may think that climate change is too depressing or too complicated for their children.

But the enormity of the climate crisis demands that educators, scientists, environmental activists, parents, and students join together to pull down the barriers between disciplines, and to rethink the curriculum. The cost of continuing with business as usual is too steep.

The good news is that addressing this crisis with the urgency that it deserves offers the possibility of revitalizing schools as young people develop the consciousness and commitment that the earth desperately needs.

‘Don’t Take Our Voices Away’: A Role Play on the Indigenous Peoples’ Global Summit on Climate Change available as PDF download.

And this work needn’t be grim, as some educators have already discovered. For instance, a workgroup of teachers in Portland, Oregon wrote a role-play on the impact of climate change on indigenous peoples throughout the world — from island nations like Kiribati to the Yup’ik of Alaska — in which students assume the personas of Indigenous activists and propose global solutions.

And of course there’s always straight-up physics and chemistry — understanding the mechanics of climate change is classic science education.

A curricular full-court press on the climate offers a compelling renunciation of the numbing test-preparation that passes for education in so many schools these days. As Rethinking Schools editors wrote recently, “This endeavor demands that young people exercise their utopian imaginations to consider alternatives of all kinds. And it invites them to ‘talk back’ to those interests that promote and benefit from endless consumption — including the publishers of their own textbooks.”

This is our chance to develop a generation for whom climate awareness is as natural as logging onto Facebook.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Posted on: Huffington Post | Common Dreams.

© 2012 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn