By Bill Bigelow

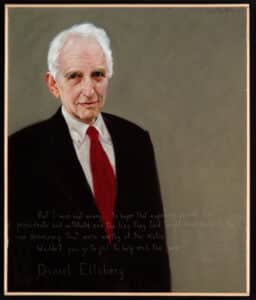

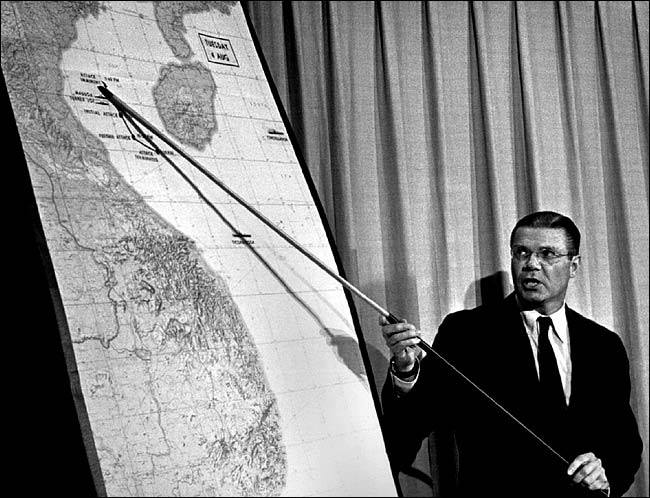

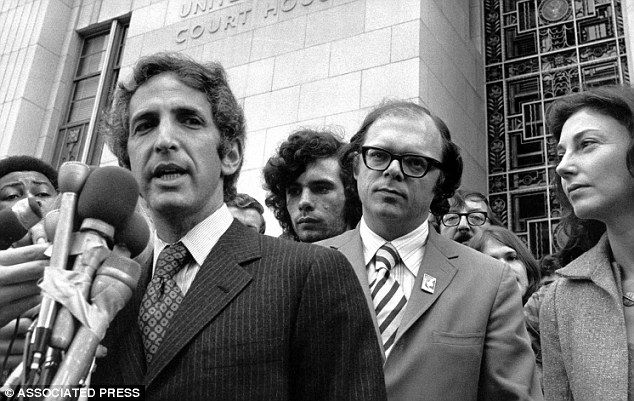

In the Academy Award-winning documentary Hearts and Minds, Daniel Ellsberg, who secretly copied and then released the Pentagon Papers, offers a catalog of presidential lying about the U.S. role in Vietnam: Truman lied. Eisenhower lied. Kennedy lied. Johnson “lied and lied and lied.” Nixon lied.

Ellsberg concludes: “The American public was lied to month by month by each of these five administrations. As I say, it’s a tribute to the American public that their leaders perceived that they had to be lied to; it’s no tribute to us that it was so easy to fool the public.”

The Pentagon Papers that Ellsberg exposed were not military secrets. They were historical secrets — a history of U.S. intervention and deceit that Ellsberg believed, if widely known, would undermine the U.S. pretexts in defense of the war’s prosecution. Like this one that President Kennedy offered in 1961: “For the last decade we have been helping the South Vietnamese to maintain their independence.” No. This was a lie. The U.S. government’s Pentagon Papers history of the war revealed how the United States had sided with the French in retaking its colony after World War II, ultimately paying for some 80 percent of the French reconquest. By the U.S. government’s own account, from Truman on, Vietnamese self-determination was never an aim of U.S. foreign policy.

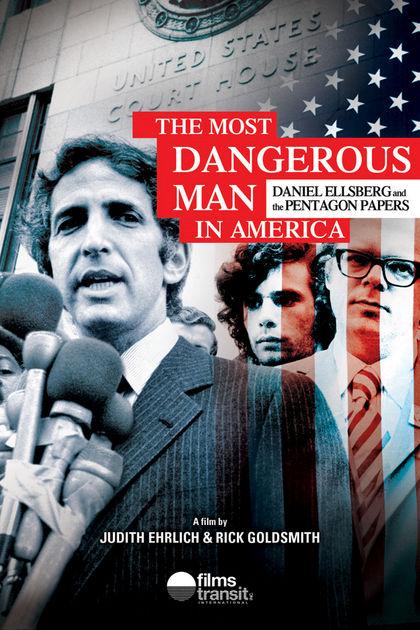

Like today’s whistle-blowers Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden, Daniel Ellsberg knew the consequences for his act of defiance. Ultimately, he was indicted on 11 counts of theft and violation of the Espionage Act. If convicted on all counts, the penalty added up to 130 years in prison. This story is chronicled dramatically in the film The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, and in Ellsberg’s own gripping autobiography, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers.

Like today’s whistle-blowers Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden, Daniel Ellsberg knew the consequences for his act of defiance. Ultimately, he was indicted on 11 counts of theft and violation of the Espionage Act. If convicted on all counts, the penalty added up to 130 years in prison. This story is chronicled dramatically in the film The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, and in Ellsberg’s own gripping autobiography, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers.

In June of 1971, Ellsberg surrendered to federal authorities at Post Office Square in Boston. Forty-two years later, few of the historical secrets that Ellsberg revealed — especially those that focus on the immediate post-World War II origins of U.S. involvement in Vietnam — appear in the school curriculum.

Corporate textbook writers seem to work from the same list of must-include events and individuals. Thus, all the new U.S. history textbooks on my shelf mention the Pentagon Papers. But none grapples with the actual import of the Pentagon Papers. None quotes Ellsberg or the historical documents themselves, and none captures Ellsberg’s central conclusion about the United States in Vietnam: “It wasn’t that we were on the wrong side; we were the wrong side.”

Textbooks resist telling students that the U.S. government consistently lied about the war, preferring more genteel language. Prentice Hall’s America: History of Our Nation includes only one line describing the content of the Pentagon Papers: “They traced the steps by which the United States had committed itself to the Vietnam War and showed that government officials had concealed actions and often misled Americans about their motives.” The textbook offers no examples.

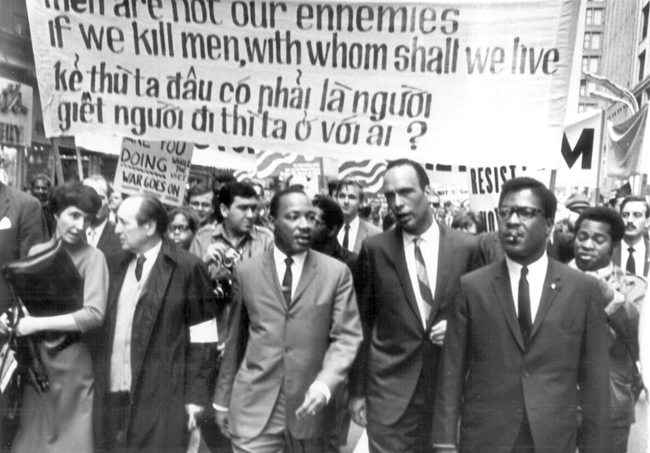

Teaching students a deeper, more complete history of the American War — as it is known in Vietnam — is not just a matter of accuracy, it’s about life and death. On the third anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Howard Zinn, author of A People’s History of the United States, spoke bluntly about what it means when we fail to confront the facts of our past wars: “If we don’t know history, then we are ready meat for carnivorous politicians and the intellectuals and journalists who supply the carving knives.”

The “we” in Zinn’s quote refers especially to the young people who will be convinced or tricked or manipulated — or lied — into fighting those wars, even if it is only “fighting” by guiding remote assassination drones from bases in a Nevada desert.

For almost 30 years, I taught high school U.S. history. I began my Vietnam unit with a little-remembered event that happened on Sept. 2, 1945. I showed students a video clip from the first episode of PBS’s Vietnam: A Television History, in which Dr. Tran Duy Hung, a medical doctor and a leader of the resistance to French colonialism, recounts the massive end-of-war celebration with more than 400,000 people jammed into Hanoi’s Ba Dinh Square. Japan had surrendered. The seemingly endless foreign occupation of Vietnam — Chinese, then French, then Japanese — was over.

Citizens of Hanoi, Vietnam, at a parade, October, 1954, celebrating the withdrawal of French colonial forces. Source: AP Photos

Dr. Hung remembers: “I can say that the most moving moment was when President Ho Chi Minh climbed the steps, and the national anthem was sung. It was the first time that the national anthem of Vietnam was sung in an official ceremony. Uncle Ho then read the Declaration of Independence, which was a short document. As he was reading, Uncle Ho stopped and asked, ‘Compatriots, can you hear me?’ This simple question went into the hearts of everyone there. After a moment of silence, they all shouted, ‘Yes, we hear you!’ And I can say that we did not just shout with our mouths, but with all our hearts.” Dr. Hung recalls that, moments later, a small plane began circling and then swooped down over the crowd. When people recognized the U.S. stars and stripes on the plane, they cheered, imagining that its presence signaled an endorsement for Vietnamese independence. “It added to the atmosphere of jubilation at the meeting,” said Dr. Hung.

Dr. Tran Huy Hung, a medical doctor and a leader of the resistance French colonialism. Source: WGBH TV

I want my students to recognize the hugeness of this historical could-have-been. One of the “secrets” Ellsberg risked his freedom to expose was that the United States had a stark choice in the fall of 1945: support the independence of a unified Vietnam, led by Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh, which had spearheaded the anti-fascist resistance during World War II; or support the French as they sought to reimpose colonial rule.

Think about all the suffering that might have been avoided had the U.S. government taken advantage of this opportunity. Howard Zinn quotes from the Pentagon Papers in A People’s History of the United States:

Ho [Chi Minh] had built the Viet Minh into the only Vietnam-wide political organization capable of effective resistance to either the Japanese or the French. He was the only Vietnamese wartime leader with a national following, and he assured himself wider fealty among the Vietnamese people when in August-September 1945, he overthrew the Japanese . . . established the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and staged receptions for incoming allied occupation forces. . . . For a few weeks in September 1945, Vietnam was — for the first and only time in its modern history — free of foreign domination, and united from north to south under Ho Chi Minh. . . .

In class, I brought this historical choice point to life with my students through a role play, in which some students portrayed members of the Viet Minh and others represented French business/government leaders arguing before “President Truman” about the future of Vietnam. (A fuller description and materials for the activity can be found at the Zinn Education Project website.) The role play depicted a make-believe gathering, of course, because the United States never included any Vietnamese in its deliberations on the future of Vietnam. Nonetheless, the lesson offers students a vivid picture of what was at stake at this key juncture.

In this and other activities, I want my students to see that history is not just a jumble of dead facts lying on a page. History is the product of human choice — albeit in conditions that we may not choose. Tragically, the United States consistently chose to side with elites in Vietnam, first French, then Vietnamese, as our government sought to suppress self-determination — perhaps most egregiously in 1954, when the United States conspired to stonewall promised elections and to prop up the dictator Ngo Dinh Diem.

Forty-two years ago this month, Daniel Ellsberg allowed himself to be taken into custody, with no clear outcome in sight. A reporter asked Ellsberg whether he was concerned about the possibility of going to prison. Ellsberg replied: “Wouldn’t you go to prison to help end this war?”

No one expects that kind of integrity from textbook corporations. But educators needn’t confine ourselves to the version of history peddled by giant outfits like Pearson and Houghton-Mifflin-Harcourt. Right now, every high school student is learning either to accept or to question the premises that lead our country to wage war around the world. As Howard Zinn suggested, if students don’t know their history, then they are “ready meat” for those who will supply the carving knives of war. Fortunately, more and more teachers around the country recognize the importance of teaching outside the textbook, of joining heroes like Dan Ellsberg to ask questions, to challenge official stories.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Posted at: Common Dreams | Huffington Post.

© 2013 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn