On Aug. 21, 1939, 26-year-old Samuel Wilbert Tucker, an innovative civil rights lawyer, launched a sit-in aimed at protesting the whites-only policy at the segregated Alexandria, Virginia, public library (later named the Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library).

Earlier in the year, Tucker and an acquaintance, retired Army Sgt. George Wilson, had been rejected in their attempts to apply for library cards and were told by an assistant librarian that the library board’s policy was “not to issue cards to colored persons” according to historian J. Douglas Smith, author of Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia.

Tucker filed a lawsuit on behalf of Wilson, arguing that taxes paid by Black citizens helped operate the library, so Blacks, therefore, “had a right to the use of its facilities.” Corporation Court Judge William Woolls held off on his ruling to give the city and library time to solve the issue with actions such as creating a separate branch library for African Americans.

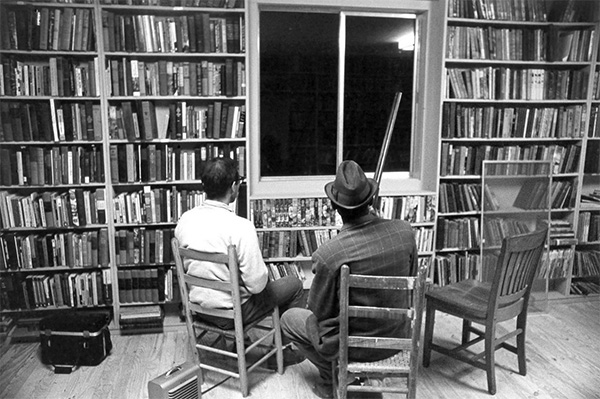

Tucker, though, “decided to force a confrontation,” according to Smith. He recruited five Black men — Otto Tucker, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, William Evans, and Clarence Strange — all between 18 and 22 years of age, to go one-by-one into the library, well-dressed, and ask to apply for borrower’s cards.

Anticipating that they would be rebuffed, Tucker had instructed the young men to select books from the shelves and quietly sit down to read, each at a different table, after being refused. The action was an early attempt at nonviolent protest, preceding by two decades the civil rights lunch-counter sit-ins that began in Oklahoma City in 1958 and Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960.

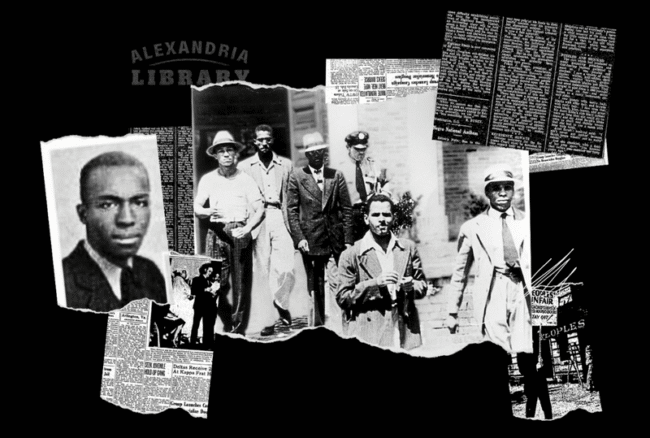

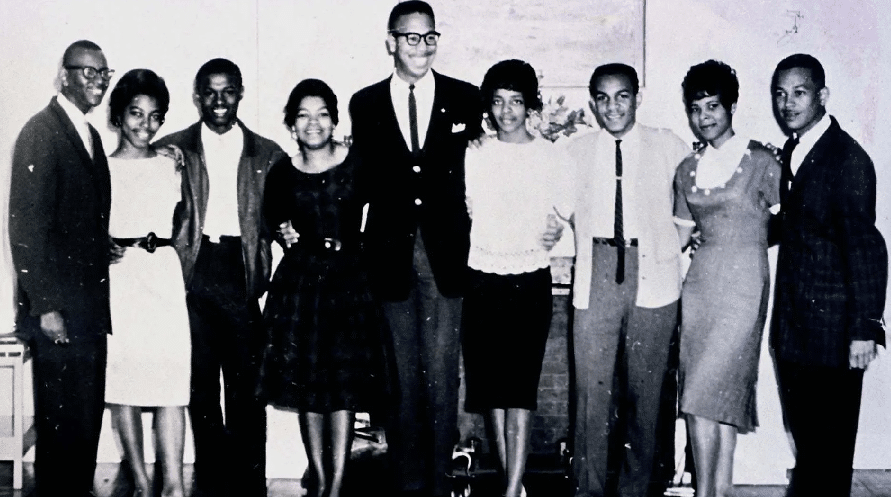

August 21, 1939. Arrest of five young Black men for peaceful protest at the whites-only “public” library in Alexandria, Va. Source: City of Alexandria

When the men did not stand up and vacate the library at the librarian’s request, police were summoned. They told the men they would be arrested if they did not leave. The men politely refused. Over an hour later, they went peacefully with the police. When they left the library, the men encountered an audience of 200-300 people, plus news reporters and photographers, waiting outside. The crowd had been gathered by Tucker to witness the discrimination and arrest. Although everyone, including the police, remained calm, City Manager Carl Budwesky ordered the police to charge the men with disorderly conduct.

The next day, in a hearing before Police Court Judge James Reece Duncan, Tucker’s questioning led the police officers to concede there was “no disorder.” Tucker accused the city of assuming that the men “were disorderly because they were Black.” City Attorney Armistead Boothe then requested the judge to postpone the case while the charges were reconsidered.

The disorderly case dragged on through the fall of 1939, with Judge Duncan allowing multiple continuances but never officially ending the matter in court.

Meanwhile, Tucker’s lawsuit on behalf of Sgt. George Wilson proceeded in Judge Woolls’ court, and Woolls finally ruled on Jan. 10, 1940, when he issued a split decision. He denied Wilson’s petition for a library card on the technicality that Tucker was the one who actually filled out the application form. But Woolls also ruled that Alexandria must permit Black residents to use the white library because there was no separate library for non-whites.

Two days after Woolls’ ruling, the Alexandria City Council undermined any thought of having an integrated library by approving money for a separate library for Black residents. Tucker denounced the council’s action as pouring insult onto injury. He wrote to city librarian, Katharine Scoggin, to say “I refuse and will always refuse to accept a card” that could be used only at the forthcoming Black library.

Tucker, who was born June 18, 1913, in Alexandria, died Oct. 19, 1990. He served in the 366th Infantry in World War II, rising to the rank of major, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. In 2000, a school in Alexandria was named for Tucker and, that same year, the Richmond (Virginia) City Council renamed a bridge in his honor. In doing so, it removed the name of Confederate General J. E. B. Stuart.

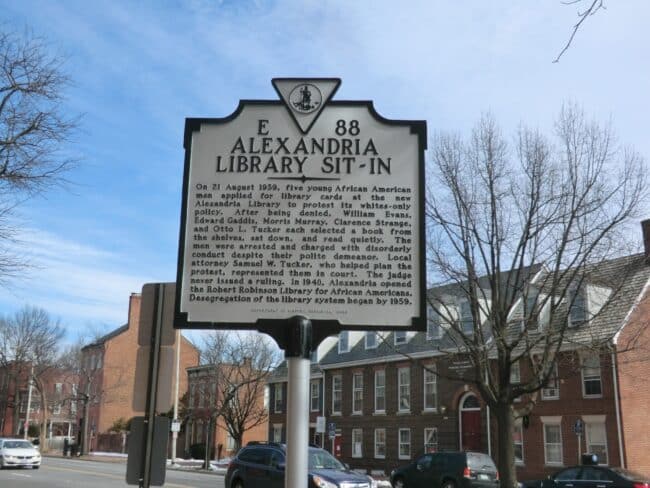

An Alexandria Library Sit-In historical marker in Old Town West in Alexandria, Virginia. Learn more about the marker here. Source: The Historical Marker Database

This description was submitted by Michael Knepler and it was informed by several sources including J. Douglas Smith’s book, “The Trials of S.W. Tucker,” “Samuel W. Tucker: A man ahead of his time,” “Samuel Tucker: Unsung Hero of the Civil Rights Movement,” and “America’s First Sit-Down Strike: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In” by Mara Mellody and Kristin Engbloom.

Additional Resources

Graphic by Fabio Murgia; photos used with permission from the Alexandria Black History Museum and Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center; newspaper images from The Washington Tribune. Source: New America

Doing Right by History: The We Are Alexandria Library Sit-In by Hannah Arata (American Library Association Public Programs Office)

What Was the Library Sit-In of 1939? Conversations with Researchers and Community Members in Alexandria, VA by Lisa Guernsey and Jazmyne Owens (New America)

80 Years Later, Alexandria Marks Civil Rights Milestone by Rick Massimo (WTOP News, Alexandria, Virginia)

Libraries, Segregation, and Civil Rights by Every Library (Medium)

1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In video recording (C-SPAN)

The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South: Civil Rights and Local Activism by Wayne A. Wiegand and Shirley A. Wiegand (LSU Press)

More stories of sit-ins at public libraries.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn