By Isabel Wilkerson

Harvey E. and Johnetta Clark, with their two children, Michele and Harvey III, in 1951. Source: Wide World.

On the evening of July 11, 1951, one of the biggest riots in U.S. history began after a young Black couple moved into an apartment in all-white Cicero, Illinois, west of Chicago. The husband, Harvey Clark Jr., was a World War II veteran who migrated to Chicago from Mississippi and was working as a bus driver. He and his wife Johnetta, who met as students at Fisk University, had been crammed with their two children in a two-room tenement with a family of five on the city’s overcrowded South Side.

The couple found more space and cheaper rents in Cicero, closer to his work, but the sheriff turned them away when they first tried to move in. “Get out of here fast,” the sheriff told Mr. Clark, shoving him out. “There will be no moving into this building.”

[The laws of the United States had begun to favor housing desegregation by this time, so,] with a court order in hand, the couple finally moved their belongings into the apartment on July 11, as a mob formed around them, heckling and throwing rocks. The mob, many of them eastern European immigrants, grew to as many as 4,000 by nightfall. The couple fled, unable to stay overnight in their new apartment.That night, the mob stormed the apartment and hurled the family’s belongings out of a third floor window: the sofa, the chairs, the clothes, the baby pictures. The mob tore out the fixtures: the stove, the radiators, the sinks. They smashed the piano the couple had saved up for their young daughter to play, overturned the refrigerator, bashed in the toilet. They set the family’s belongings on fire and then firebombed the building, leaving even the white tenants homeless. The rioters overturned police cars and threw stones at firefighters who tried to put out the fire.

The Illinois Governor, Adlai Stevenson, had to call in the National Guard for the first time since the 1919 race riots in Chicago. It took more than 600 guardsmen, police officers and sheriff’s deputies to beat back the mob that night. It took three more days for the rioting over the Clarks to subside.

The Clarks were prevented from spending a single night in Cicero. A total of 118 men were arrested in the rioting but none were indicted. Instead, the rental agent and the owner of the apartment building were indicted for inciting a riot by renting to the Clarks in the first place.

Years later, their young daughter, Michele Clark (shown in photo above with her parents and young brother, Harvey III), would grow up to become the first Black network television correspondent (on CBS). She tragically died in an airline crash in 1972 in Chicago, only blocks from the place that her parents had tried to integrate.

Years later, their young daughter, Michele Clark (shown in photo above with her parents and young brother, Harvey III), would grow up to become the first Black network television correspondent (on CBS). She tragically died in an airline crash in 1972 in Chicago, only blocks from the place that her parents had tried to integrate.

The Cicero riot attracted worldwide attention and became a symbol of both northern hostility to the arrival of millions of African-Americans during the Great Migration and of underlying belief systems that reverberate to this day.

This description is excerpted with permission of the author from The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson.

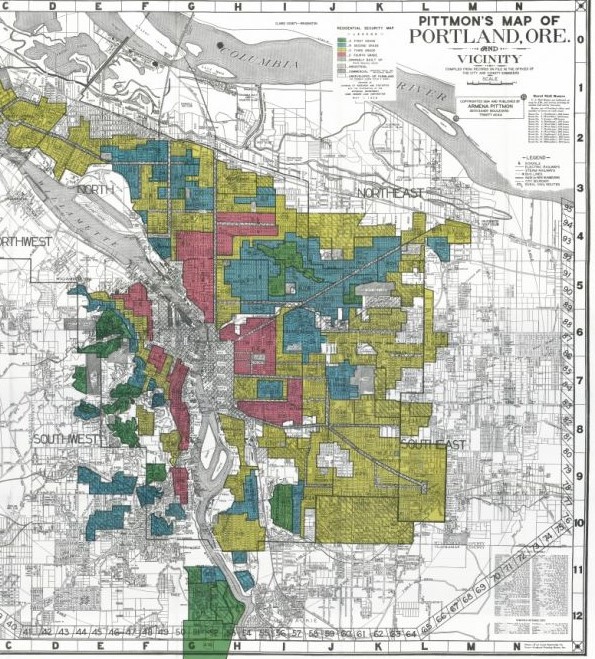

Learn more from the book The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein. Introduce this history to students with the free downloadable classroom lesson, “How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. Harvey Clark is one of the people featured in the mixer lesson.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn