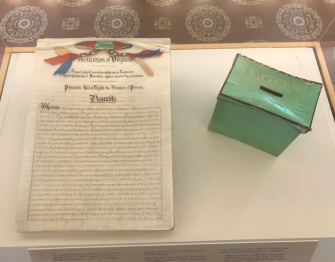

Nearly three years later, on April 17, 1868, Virginia’s “Underwood Constitution” was passed in Richmond by Radical Republicans. It extended the vote to Black men and established schools for all children. Credit: Gregory Schneider/Washington Post

Before the Civil War was even over, African Americans in Norfolk were organizing for suffrage. They met in Mechanics Hall in Norfolk in April of 1865 to create the Colored Monitor Union Club (CMUC).

The Club became a main political institution through which African Americans organized their resistance to the Black Codes being enacted across the south in the months following the war’s end, declaring, “traitors shall not dictate or prescribe to us the terms or conditions of our citizenship, so help us God.”

When the provisional governor called for state assembly elections in May, it was unclear to the members of the CMUC what kind of response might meet the attempts of Black people to vote. CMUC scouting parties sent out on May 25, election day, determined that most wards would not allow Black voting, with a few minor exceptions. All said, about three hundred African Americans cast official ballots.

Nevertheless, a thousand Black people poured into the Bute Street African Methodist Church to cast a separate ballot. Vincent Harding said that this meant Norfolk was the birthplace of the Black “freedom ballot.”

Though these ballots were not counted in official election results, they signaled the strategic approach of the Black community to achieve full political participation in Virginia.

Read More

African Americans and Politics in Virginia (1865–1902): Attempted Black Suffrage in Norfolk

“An Appeal from the Colored Citizens of Norfolk, Va., to the People of the United States” (June 5, 1865) via the Colored Conventions Project. See excerpt below.

Fellow Citizens:

The undersigned have been appointed a committee, by a public meeting of the colored citizens of Norfolk, held June 5th, 1865, in the Catherine Street Baptist Church, Norfolk, Va., to lay before you a few considerations touching the present position of the colored population of the southern States generally, and with reference to their claim for equal suffrage in particular.

We do not come before the people of the United States asking an impossibility; we simply ask that a Christian and enlightened people shall, at once, concede to us the full enjoyment of those privileges of full citizenship, which, not only, are our undoubted right, but are indispensable to that elevation and prosperity of our people, which must be the desire of every patriot. . . .

6th. Resolved, That the safety of all loyal men, black and white, in the midst of the recently slaveholding States, requires that all loyal men, black or white, should have equal political and civil rights, and that this is a necessity as a protection against the votes of secessionists and disloyal men.

7th. Resolved, That traitors shall not dictate or prescribe to us the terms or conditions of our citizenship, so help us God.

Find resources below to teach outside the textbook about the Reconstruction era and the long, ongoing struggle for voting rights in the United States.

Read the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn