An 11th-grade student leaned back in his chair at Lincoln High School in Portland, Oregon, and said, “Absurd. That is the only way to describe those numbers. They are absurd.” He and his classmates had just read statistics about the racial wealth gap in their Political Economy class: White households are worth at least 10 times as much as Black households; only 15 percent of whites have zero or negative wealth while a third of Blacks do; Black families making $100,000 typically live in the kinds of neighborhoods inhabited by white families making $30,000. These numbers are absurd, and they are not accidental.

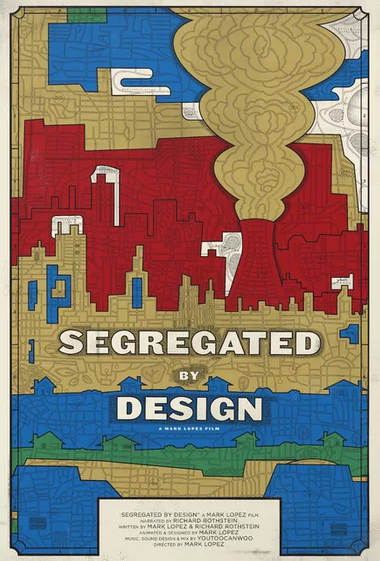

This lesson introduces students to the 20th-century housing policies that bankrolled white capital accumulation while halting Black social mobility — and contributed to the absurd injustice of the modern wealth gap.

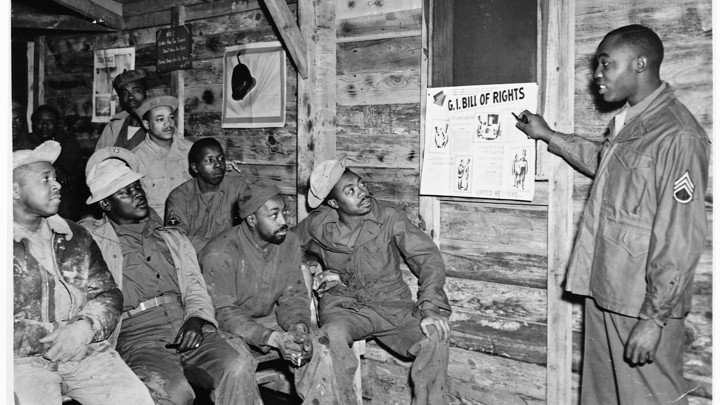

The mixer role play is based on Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law (Liveright, 2017), which shows in exacting detail how government policies segregated every major city in the United States with dire consequences for African Americans. Students encounter stories about the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, the Federal Housing Administration, the Veterans Administration, redlining, blockbusting, zoning, racially restrictive deeds and covenants, and move-in violence. Students also meet many people who fought bravely against this dizzying array of racist policies. This could be an introductory lesson in a unit on housing segregation, gentrification, the racial wealth gap, and/or reparations in a U.S. history, economics, or government course.

For more context and background on this lesson, read the online article, The Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated the United States by Richard Rothstein.

Roles for this mixer include:

- Joseph Lee Jones, a Black man married to a white woman who sued to be able to live in a new housing development in St. Louis

- Frank Stevenson, a Black Ford employee in California who faced stiff obstacles when trying to purchase a home

- David Bohannon, a white real estate developer in California who built new homes which excluded African Americans

- Wallace Stegner, a white writer who tried to assist Black homebuyers but faced resistance from the FHA

- Floyd Lowe, president of the California Real Estate Association

- Harold Ickes, the secretary of the interior under President Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Walter Jackson, who, with other Black workers, won the right to move into the Sojourner Truth Housing Project in Detroit

- Edward Jefferies, who in 1945 ran to be re-elected mayor of Detroit

- William Warley, an African American lawyer who was blocked from buying a home in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1915

- Harland Bartholomew, a white planning engineer for the city of St. Louis

- Frederick Ecker, president of Metropolitan Life Insurance Company

- President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) that paved the way to homeownership for millions of Americans

- Gabriel Eaton, who worked for the Federal Housing Administration (FHA)

- Arnold Cabot, who worked for the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), one of the many government agencies formed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to address the economic crisis of the Great Depression

- Robert Mereday, a Black WWII veteran who helped started a trucking company and helped build the suburbs, even though he wasn’t allowed to live there

- William Levitt, a white real estate developer, often called the father of suburbia

- J. C. Nichols, a real estate developer who developed a way to keep my developments all white at a time when the Supreme Court was beginning to question whether it was constitutional to use government power to bar Black people from buying property in certain areas

- Ethel Shelley, a Black woman who bought a home in a white neighborhood, was sued for eviction, and went to the Supreme Court

- “Norris Vitchek”, a real estate “flipper” in blockbusting

- Clyde Ross, served in WWII, and in 1947 moved to Chicago, where he became a taster for Campbell’s soup.

- Ethel Weatherspoon, one of the founding members of the Contract Buyers League (CBL), who bought a house “on contract” in North Lawndale in Chicago in the 1950s

- Wilbur Gary, a Black WWII veteran who faced racist violence due to buying a home in a white community

- Daisy Myers, who bought a home with her husband in Levittown, Pennsylvania and was met with racist violence

- Harvey Clark, an Air Force veteran who worked as a bus driver in Chicago

- Anne Braden, a white journalist and civil rights activist

- Lou Fushanis, who sold houses in Chicago and developed a scheme to make a lot of money off the racism of government housing policies

- Langston Hughes, an esteemed African American poet and writer

- Gerald Cohn, a white school teacher

- Robert Weaver, the secretary of housing and urban development in the mid-1960s, appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson

- Katherine Peden, a white Democratic politician from Kentucky, the only woman on the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (known as the Kerner Commission)

- Catherine Bauer Wurster, a white housing expert and advisor to the U.S. Housing Authority (USHA), a government agency that helps manage and finance housing

- J. Dexter Peach, chairman of the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), a nonpartisan government agency that issues investigative reports to assist Congress in writing good policies and laws

- Vincent Mereday, a Navy veteran, who fought in WWII, and worked for his uncle’s trucking and hauling company after the war

- Steven Barnard, who helped write a report for the New Jersey State Attorney General’s Office in the 1960s about the impact of building a new interstate highway on the city of Camden

| This teaching activity includes instructions on its final page for facilitating asynchronous or synchronous online instruction with remote handouts. Read about teaching with Zinn Education Project lessons remotely and find additional lessons with remote handouts in our Fall 2020 guide, Suggestions for Teaching ZEP Lessons Remotely: Recommitting to the Why — If Not the How — of Our Pedagogy. |

From the author of The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein:

I recommend this important Zinn Education Project lesson, “How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century,” for use by middle school to college instructors.

I recommend this important Zinn Education Project lesson, “How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century,” for use by middle school to college instructors.

Based on The Color of Law, it teaches about residential segregation in a fashion that is both accurate and creative. With it, teachers can correct the misinformation in textbooks that typically promote a myth that we came to be segregated by private actions alone. If younger generations finally learn the truth with a lesson like this, they’ll be in a better position to redress the unconstitutional segregation and inequality that was created by our government.

Classroom Stories

Students in my class are well aware of the fact that things are not as they should be in the United States. Specifically, they are aware of the fact that the color of their skin, in many ways, determines where they live, the wealth their families have (or have not) acquired, and the opportunities presented to them throughout their lives.

However, despite the fact that awareness of inequality is high, the understanding of WHY inequality, racism, and segregation still exists remains a mystery to many students. Or, they have been indoctrinated with the not-so-subtle message that these issues still exist purely as a result of individual racism or prejudice. Not many of these young people realize that the dire circumstances they observe are the result of systematic policies that have shaped our country for decades, and are still doing so today.

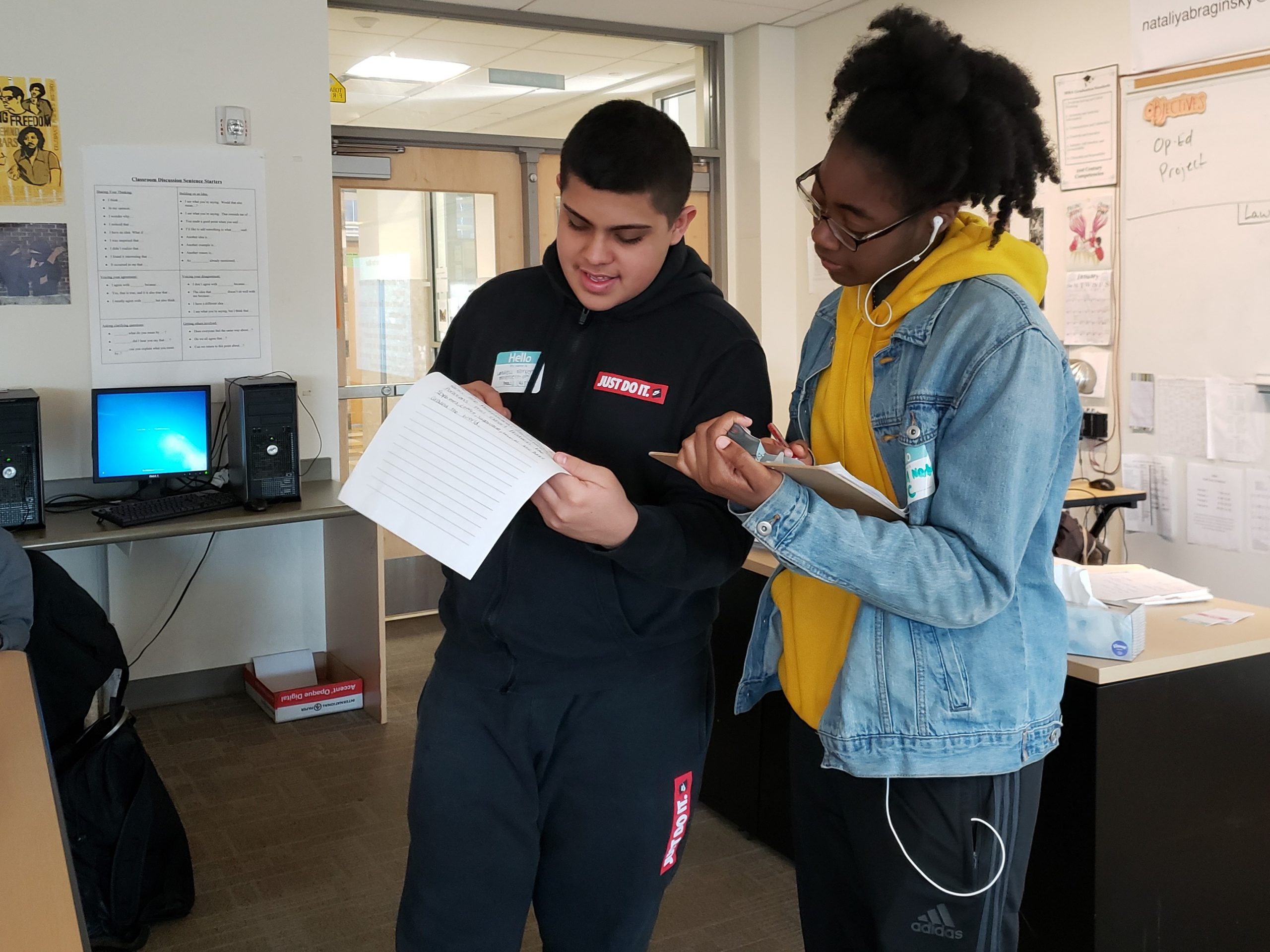

As soon as students received and began reading their roles for the lesson How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century, I saw eyes begin to widen. Frantic highlighting and slight gasps of shock, along with giggles of disbelief, began to echo through the classroom. This is when you know students are about to learn something, and learn something that matters. Minutes later, the entire class was on their feet, moving to find someone they could share their “story” with. Maybe it was a story of move-in violence, or the story of how their character used the prejudiced voting population in the United States for their own personal gains. Whatever it was, students were eager to share and to listen.

After nearly an hour of mingling, the class began to discuss what they discovered. The students who played the government officials, the building contractors, and the loan officials oscillated between outrage and nervous chuckles of disbelief, while those who played Black community members seemed to shake their heads in familiar understanding. Was any of the information on prejudice, or the horrifying experiences for the Black community, new to them? Not really. However, what they hadn’t understood was the intentional and systemic nature of the government’s involvement in these practices and their outcomes.

At the end of the day, the entire class seemed to leave the room with a newfound sentiment of “now this makes sense.” Now it makes sense as to why the results of the blatant segregation from decades and decades ago still exists. Now it makes sense as to why I live where I live, and you live where you live. Now it makes sense as to why the money resides in certain homes, but not others. And the question that now exists in students minds is not “why,” but rather “how” — “How do we change things? How do we learn more? And how do we make a difference?”

I used the lesson titled, How Red Lines Built White Wealth, in order for students to learn about red lining and institutionalized racism. The mixer lesson was very engaging for students, allowing them to move around the classroom, collaborate with one another, and learn new information that they hadn’t studied before.

As a teacher, the lesson was extremely detailed and made me feel prepared. From introduction activities to exactly how to run the mixer to multiple options for follow up activities, the lesson was robust and meaningful. I always check Zinn Education Project for new and exciting lessons that keep students engaged and speak truth!

The Zinn Education Project lessons Stealing Home: Eminent Domain, Urban Renewal, and the Loss of Community and How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century are invaluable help in illustrating concepts like urbanization and its impact on marginalized communities. These resources provide historical context to understand how practices like eminent domain, urban renewal, and redlining have led to displacement of entire communities. As an adjunct lecturer of course on Latinos in the United States at a Hispanic-serving institution in New York City, many of my students are unfamiliar with the language and vocabulary of displacement that has affected their communities.

However, I believe it is essential to emphasize that there is hope. The resilience of marginalized communities — through grassroots organizing, mutual aid societies, and cultural preservation — offers a model of resistance. I encourage my students to recognize their potential as change agents in their communities. By participating in efforts like community centers, cultural events, and activism, they can preserve their identities and resist further displacement. I want them to see that they are part of a larger movement for justice and equity, and they have the power to challenge the structures that perpetuate marginalization. Their activism, whether through art, music, or direct action, is not only a form of resistance but also a tool for transformative change.

Redlining-a matter that needs discussion when considering BLM. To think that it still affects our lives.

Thank you for creating this. I really like how you organized it and added the individuals, which surely makes it feel more personal/real. I will definitely try this out this year.

In past classes, I have used part of Episode 3 of Race: The Power of Illusion (PBS), beginning at Chapter 10 (DVD scene #10 in the transcript) in conjunction with the Racial Dot Map, which helps to visually illustrate part of the legacy of redlining.

Other sources I had students explore last year to drive home the ongoing effects:

• Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America (University of Richmond)

• “Whites are mainly to blame for air pollution, but blacks and Hispanics bear the burden, says a new study” (The Washington Post, March 12, 2019)

• “How Redlining’s Racist Effects Lasted for Decades” (The New York Times, August 24, 2017)

• Segregation in the North; A Case Study: Boston. Digital History.

• “How Government Redlining Maps Pushed Segregation in California Cities [Interactive]” (KQED, Apr 27, 2016)

• “The American Dream: Does Your Zip Code Determine Your Destiny?” (a 20 min. podcast from Pew Charitable Trusts, January 4, 2019) This also has some interesting links to other projects/websites.

• “3 things schools should teach about America’s history of white supremacy” (The Conversation, February 29, 2019)

• “Blacks Still Face Redlining on Housing” (The New York Times, April 14, 2018)

• “Facebook Faces a Reckoning for Redlining” (The New York Times, March 29, 2019)