Sylvia McAdam Saysewahum of Idle No More, one of the many activists introduced in this lesson.

The climate crisis is a global emergency that requires, in the words of UN scientists, “unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.” Or as Greta Thunberg, founder of the global student strike for climate movement, says, “We can’t save the world by playing by the rules, because the rules have to be changed. Everything needs to change, and it has to start today.”

For educators, this means it is no longer enough for our students to simply understand the science of climate change, or how the climate crisis currently affects people and places around the world.

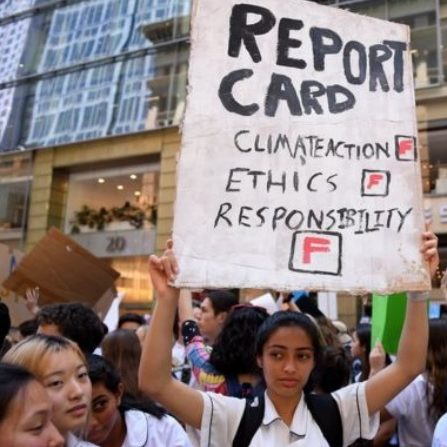

If we focus only on the causes and effects of the climate crisis, then we miss out on the story of students organizing school strikes for climate across Australia and Europe. We miss out on how protests at Standing Rock have inspired a generation of new activists, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. We miss out on the imaginative responses to the climate disaster that have grown out of communities across the world such as Casa Pueblo in Puerto Rico.

We wrote this mixer to highlight some of the stories of climate justice activists, especially young people, who are organizing toward climate action. We chose roles that bring together various strands of the climate justice movement, and that highlight the broad coalition of groups are working toward the goal of a just transition — including people who students might not recognize as climate activists.

We wrote this mixer to highlight some of the stories of climate justice activists, especially young people, who are organizing toward climate action. We chose roles that bring together various strands of the climate justice movement, and that highlight the broad coalition of groups are working toward the goal of a just transition — including people who students might not recognize as climate activists.

By bringing the story of the climate justice movement to our classrooms, we create an opportunity for our students to begin to see themselves as part of this movement — as activists — capable of creating the change that so often feels out of reach.

Mixer Roles

|

|

Classroom Story

I use the lesson, Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists: A mixer on the people saving the world as part of my unit on climate change. In my unit, we asked “what is justice” and what it means in regard to climate change. One of the goals of our school is for our students to “take action,” so this lesson gives them role models on how to take action in regard to climate change.

I used it with three of my classes, 125 students total. The students responded well to playing roles including Eve Miller, Harry Smiskin, Victoria Barrett, AOC, Kathy Jetnil-Kijner, Mishka Banuri, Linda Garcia, Hannah Jones, Simmone Ahiaku, Henry Red Cloud, Joanna Sustento, Lucie Atkin-Bolton, Greta Thunberg, Arturo Massol-Deya, Xiuhtezcatl Martinez.

The directions in the lesson were helpful in making the time productive, and I liked the concept of a mixer as the setting for the lesson. At my school, we use a variety of strategies from “The Strategic Teacher” and SRI, but I have never used a mixer before. It was a nice variation that added novelty to the lesson structure, and the students responded well to it.

I used the Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists in my classroom and it helped my students better understand the variety of people who are engaged in climate justice work.

First, I instructed my students to conduct research on their given activist (I used all United States-based people, as this was for a U.S. History class) and come to class with information beyond that on the blurb. Then, I asked them to make an infographic about their person to use as a prop in the mixer. Later, I hung it up in the dining hall for the whole school community to see.

It was great for them to see young people like themselves taking action around the country. The words and actions of their activists stayed with them.

I used the Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists mixer in my 300-level college class Globalization and the Environment. This allowed me to shift the focus of the class away from doom-and-gloom prognosticating and give students real examples of how positive change can work.

Because the class is small (fewer than 20 students), I pre-selected activists whose work seemed most relevant to the course content. I chose an activist to portray myself and I joined the mixer, balancing out an odd number of students to maintain 1-to-1 conversations at all times.

After class, I had students choose an activist to profile. In their essays, they were asked to analyze how the activist had accomplished their work and with whom they had partnered. Because we had been discussing international political actors (NGOs, IGO, nation-states, TNCs, etc.) in class, I directed them to discuss the activist’s partnerships with any such entities. This essay deepened the connection of the activity to the course content.

The students loved it. When I collected midterm feedback, many students asked for more exercises like the Climate Justice Activist Mixer.

We used materials from the Zinn Education Project, Rethinking Schools, and Teaching for Change with our 7th grade to create an interdisciplinary, experiential project that explored Indigenous Perspectives on Climate Change. It was the perfect way to tie together our humanities unit on Indigenous Perspectives on American History with the STEM unit on deep time and extinction-level events.

Our students prepared for the ‘Don’t Take Our Voices Away’ indigenous people’s climate summit simulation as a final learning demonstration. Taking on the perspectives of various indigenous groups was something our students took seriously as they researched both the cultures and climate challenges faced by the groups. Then, at the summit, they did presentations that explained the priorities and needs of those groups before launching into negotiations about how to best communicate those perspectives with the rest of the world.

Leading up to the summit, we took a climate justice gallery walk using photos shared on the ZEP website, researched indigenous climate activists, and also did the Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists mixer. Those activities were the perfect scaffold to the summit. Overall, I saw my students develop deep understanding and empathy through the interactive and experiential materials provided by the Zinn Education Project.

I am grateful to have participated in a workshop where I learned how to use them. Now that I am at a school where our model centers experiential project based learning, these materials have become an invaluable resource.

Spring semester of 2020, as inklings of the pandemic were just beginning to hit the news, I was helping to facilitate a college study abroad program on Climate Justice. To begin the semester, our group of 30 students crowded into the top floor of a wonderful community space/free library in Oakland, California where we all watched the documentary Necessity. After the film, co-founder and ED of the Climate Defense Project Kelsey Skaggs humbly shared their life journey and relationship to climate work.

Only a few weeks later, after the students learned about the climate effects on the communities of the Mekong Delta while in Vietnam, and had arrived in Morocco to hear from urban activists, COVID-19 interrupted the program and the lockdowns began. For a harrowing week my colleagues and I worked around the clock to organize emergency evacuations for the students while borders were closing everywhere. And while everyone was eventually ‘repatriated,’ much to the credit of their own self-organizing efforts, that schism, that disruption to our learning community was never fully addressed. I, along with many around the globe, lost my livelihood.

Yet, in my long period of unemployment, I began to put into practice some of the things I had previously only taught about in classrooms around the world. Instead of teaching about social movement theory, I became part of social movements. From the George Floyd uprisings to Black Lives Matter to Defund/Abolish the Police to union organizing to Defund Line 3 to Palestinian solidarity, my praxis shifted from the classroom to the streets. Today marks two years and almost two months since I last gathered together in person with a group of students to learn about climate disobedience.

And while I haven’t had the privilege to facilitate this brilliant lesson ‘Teaching Climate Disobedience‘ amidst the collapse of the study abroad industry, I learned how to embody my own practice in a new way. I came into deeper relationship with organizers and activists, with nowhere else to be during the pandemic but in the streets, having each other’s backs. So when Indigenous leadership from Minnesota made the call for all people to gather to uphold their treaty rights, I became part of that story as well. One day soon I will work with students again, and when I facilitate the climate justice mixer, I can share my personal stories of being on the frontlines with Tara Houska and the many thousands of people who stood up to the oil and gas industry in the summer of 2021.

Note: The teachers who wrote this lesson would like feedback from fellow teachers in the Zinn Education Project community before it is finalized.

Note: The teachers who wrote this lesson would like feedback from fellow teachers in the Zinn Education Project community before it is finalized.

Send your feedback after using the lesson to: www.zinnedproject.org/share-your-story You will receive a climate justice book in appreciation.

We will alert you once the authors have received enough feedback to make revisions and to post this lesson in our standard layout.

Find more stories of climate justice activists in the Teen Vogue (January 3, 2020) article, 9 Climate Activists of Color You Should Know.

Vic Barrett uses pronouns he/him.