Adrià Fruitós.

By Rachel Boccio

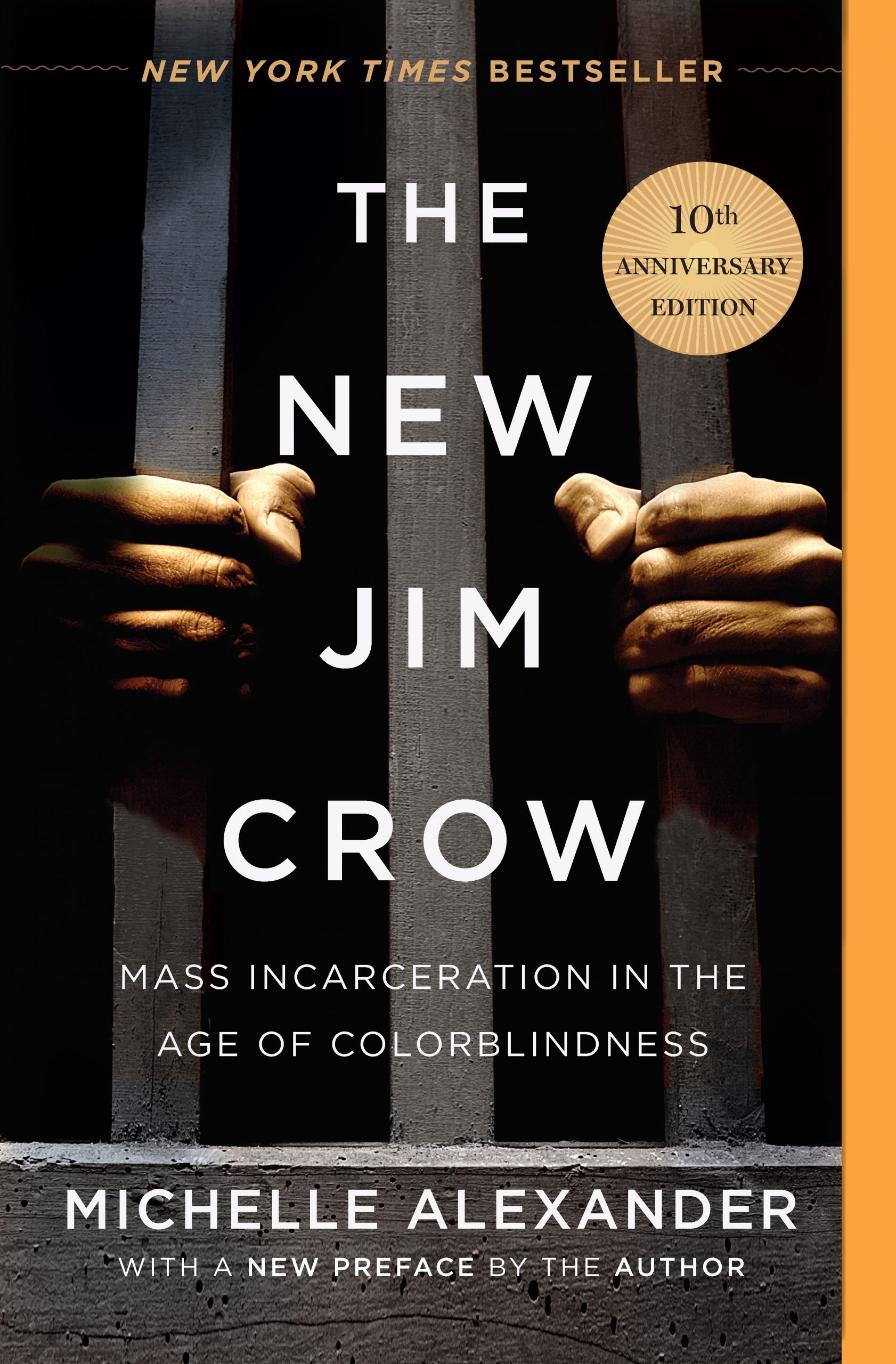

Manson Youth Institution is a maximum security correctional facility for adolescent males tried and sentenced as adults in the Connecticut Department of Correction. Its population is composed mostly of poor men of color with histories of abuse, detention, and truancy. Education is mandatory for the majority of Manson’s inmates: boys file up to school — right side of the yellow line, no talking, IDs out, shirts tucked, heads down — bearing the anger, frustration, fear, and loneliness that inheres to incarcerated life. The negativity is palpable; it can overwhelm staff, including teachers. Most days, there are multiple heated altercations (sometimes physical fights) on the school line; students enter class irritated, refusing to work. It’s here, in Manson’s High School Program, where I have taught English for 20 years.

In the summer of 2016, I attempted a special course called “Teaching the Political Manifesto.” For our purposes, I defined “manifesto” as a declaration of political vision and desire. We analyzed historical and contemporary examples, such as David Walker’s Appeal (1829), the United Negro Improvement Association Manifesto (1926), the Port Huron Statement (1962), the Black Panther Party’s Ten-Point Program (1967), and Ralph Nader’s Concord Principles (1992), noting commonalities in structure including the use of “policy points” as a framing device. My goal was for students to join me in thinking about how the literary form of manifesto makes a certain type of political thinking possible, but also about the genre’s limits.

Our touchstone text was the Leap Manifesto, a Canadian call to action that sees transformative, justice-based action as the only legitimate response to severe global warming. This document developed from a two-day conference held in Toronto in the spring of 2015. Attendees represented a cross section of Canada’s activists working on Indigenous and labor rights and on environmental and social justice. I chose this text because unlike other manifestos we studied that summer (ones that more directly engaged with matters of race and policing), the Leap centered on a threat that my students knew very little about.

Our touchstone text was the Leap Manifesto, a Canadian call to action that sees transformative, justice-based action as the only legitimate response to severe global warming. This document developed from a two-day conference held in Toronto in the spring of 2015. Attendees represented a cross section of Canada’s activists working on Indigenous and labor rights and on environmental and social justice. I chose this text because unlike other manifestos we studied that summer (ones that more directly engaged with matters of race and policing), the Leap centered on a threat that my students knew very little about.

It was my hope that they might connect the climate crisis (and its democratic openings) to other forms of injustice they were more familiar with.

Download article to continue reading.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2018-19 issue of Rethinking Schools.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2018-19 issue of Rethinking Schools.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn