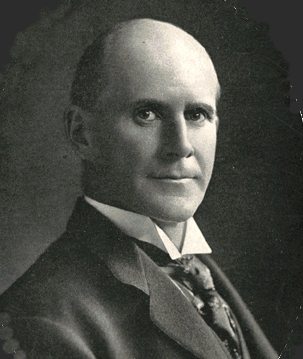

Marie Equi. Source: Public domain.

By Jeff Biggers

On Oct. 17, 1920, Marie Equi entered the San Quentin prison to serve a one-year term. “I’m going to prison smiling,” the Portland newspapers reported Equi stating. “But I am not through. I shall keep on fighting until I die.”

In 1916, Portland physician Marie Equi outmaneuvered the clutches of police and war-frenzied mobs when she put on lineman spurs and scaled a telephone pole — a twentieth-century replica of the liberty pole — and unfurled an anti-war banner, DOWN WITH THE IMPERIALIST WAR. The persecution of seemingly “other” voices, such as Equi’s, an out-spoken proponent of labor laws, birth control, and pacifism, reflects an anti-American strain in our historical experience — not the norm. The very definition of a witch hunt is often misleading, too; there are no witches, but there are resisters to a status quo bewitched by its own powers, yet unable to enforce an unpopular cause.

Like the seditious editors a century before her, and the anti-Trump protesters a century after her, Equi was no stranger to trumped up charges of felony rioting.

Declaring the American push into World War I as “nothing but capital against labor, a rich man’s war,” Equi was physically assaulted for driving her car alongside a Portland “War Preparedness” parade in 1916, defiantly unveiling an American flag framed by the banners, PREPARE to die, workingman — jp morgan & co. want preparedness for profit — thou shall not kill. She had already been arrested for disseminating birth control publications and assisting abortions; as a well-known speaker, she drew the police at rallies in support of radical union strikes by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

It was Equi’s personal life that compounded the vicious attacks by federal agents and the attorney general’s office. One report in 1918 referred to the openly lesbian doctor and her community of women as “perverts and degenerates.” According to historian and biographer Michael Helquist, Equi seemed to “stir an inordinate amount of loathing and fear.”

The American entry into World War I was not as popular as those “preparedness” marches would suggest. In his book on the war, To Raise an Army, John Whiteclay Chambers II studied the lack of popularity of the military draft, estimating that between 2.4 and 3.6 million men resisted service. This was particularly true in the South, according to historian Jeanette Keith, who concluded “the majority of southern draft resisters opposed conscription, not because the draft was federal, but because it forced them to support a cause they considered irrelevant at best, dubious at worst.”

With radical labor groups leading widespread public opposition against the war, President Woodrow Wilson rammed through the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 largely to contain the growing dissent to an unpopular war. The Sedition Act, in fact, was passed in the last year of the war. Its language even borrowed from the historical debacle of John Adams’s Sedition Act of 1798:

No American was allowed to utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States.

In the hands of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, the Acts were exploited to crack down on immigrants and political activists beyond the realm of any threat by wartime activists. Targeting labor organizations, Socialist Party members, and pacifists, the government rounded up, arrested, and imprisoned more than 2,000 Americans.

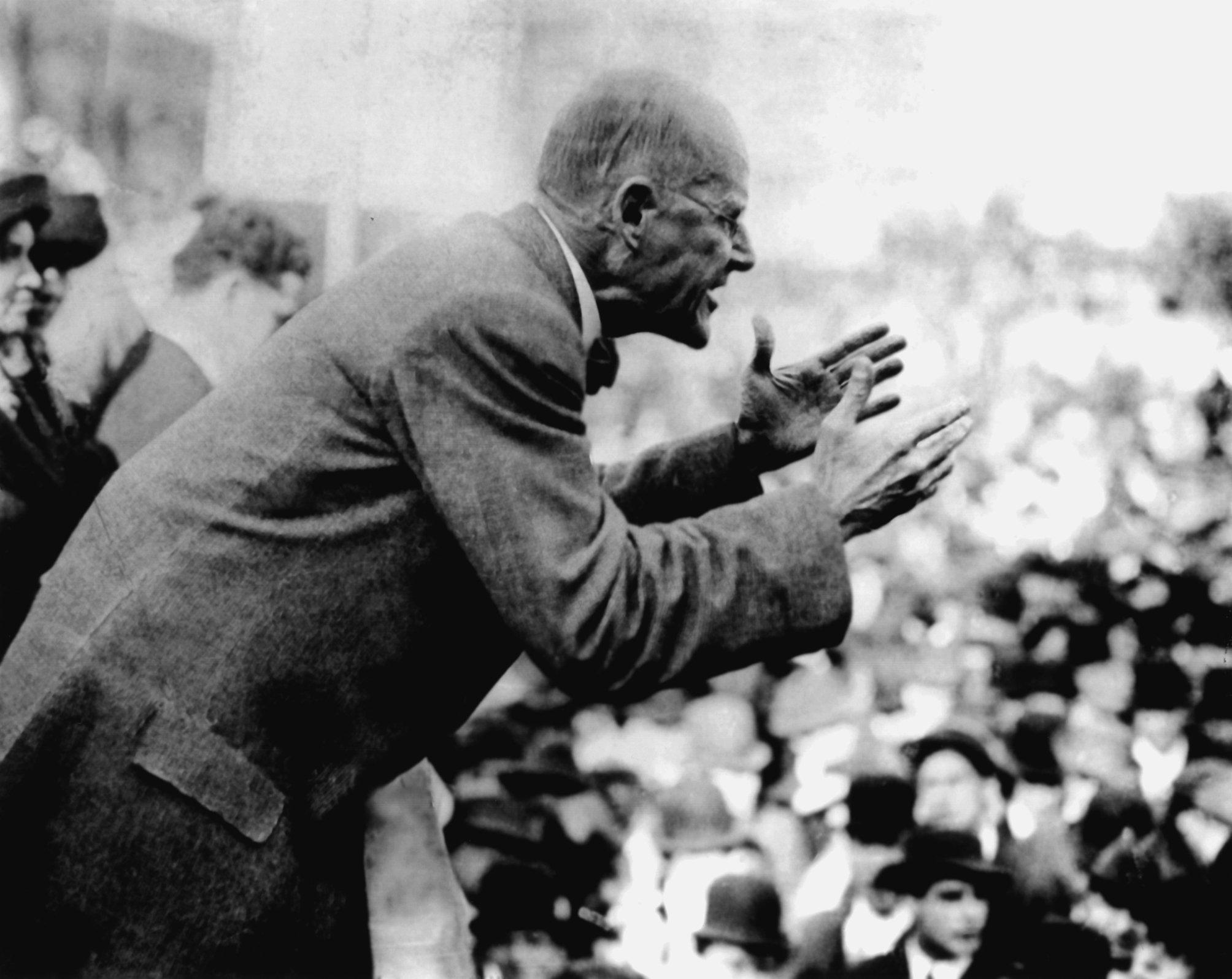

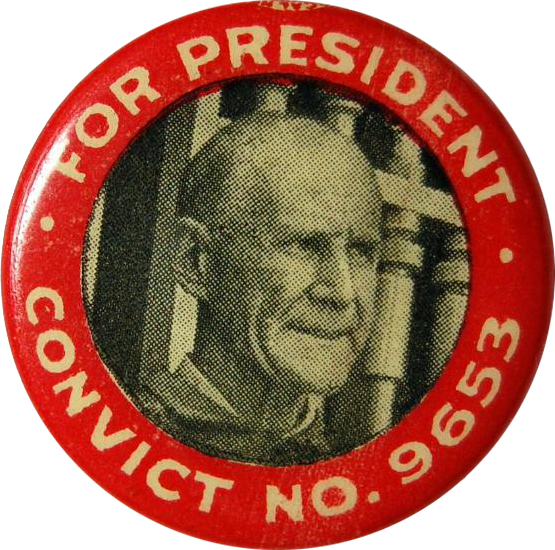

Although she had been warned, Equi’s anti-war resistance persisted, nonetheless. In fact, she was arrested in Portland on the same day as Eugene Debs. “Oh, it’s very easy to attend a civic lunch, listen to a number of complimentary speeches from well-mannered and admiring people, while you wear your best clothes and play the part of a hero,” she told an interviewer. “But to go out and mount a soapbox and declare war against the organized forces of capitalism is quite a different matter. The task of veering public opinion was never an easy one.”

A month after the war came to an end in 1918, Equi was convicted for sedition in an Oregon court, by a judge who ruled she did not “keep quiet.” Most observers saw the prosecutor’s case as politically motivated. “For years I have been hounded in this town,” Equi said when the guilty decision was announced. In appealing her case to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and then the Supreme Court, Equi’s defense team called out the attacks by the prosecution on her “private moral characters” as a lesbian.

In many respects, Supreme Court Justice Holmes had vindicated Equi’s resistance in a subsequent case. Writing a surprise opinion of dissent on the Abrams v. United States decision in 1919, which convicted two men for distributing anti-war material in violation of the Espionage and Sedition Acts, he had abruptly shifted course in light of the broad crackdown on dissent and freedom of speech. Joined by Justice Louis Brandeis, Holmes wrote:

That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system, I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.

Holmes’s dissent “caused a sensation,” according to author Thomas Healy, a former federal appeals court law clerk and reporter, and author of a history of the Supreme Court case. “Conservatives denounced it as dangerous and extreme. Progressives hailed it as a monument to liberty. And the future of free speech was forever changed.”

Equi, who remained a fixture of resistance until her death in 1952, put it best: “I’m going to speak when and where I wish,” she had said at one of her rallies in Portland. “No man will stop me.”

Adapted from Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition by Jeff Biggers.

Related Reading: “What We Can Learn From Portland’s “Queen of the Bolsheviks”” by Kim Kelly. The Nation.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn