Most books leave out the story of the 381-day bus boycott involving thousands of people.

Issues of racism and direct confrontation between African American and European American people in the United States are usually considered too sensitive to be dealt with directly in the elementary school classroom. When African Americans and European Americans are involved in confrontation in children’s texts, the situation is routinely described as a problem between individuals that can be worked out on a personal basis. In the few cases where racism is addressed as a social problem, there has to be a happy ending.

Most books show Rosa Parks on her own and leave out her role with the NAACP and her trips to the Highlander Center. (Pictured here with freedom school educator Septima Clark.)

This is most readily apparent in the biographical treatment of Rosa Parks, one of the two names that most children associate with the Civil Rights Movement, the other being Martin Luther King Jr. The image of “Rosa Parks the Tired” exists on the level of a national cultural icon. Dozens of children’s books and textbooks present the same version of what might be called “Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott.”

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson was one of the main organizers of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Rosa Parks was a poor seamstress. She lived in Montgomery, Ala., during the 1950s. In those days there was still segregation in parts of the United States. That meant that African Americans and European Americans were not allowed to use the same public facilities such as restaurants or swimming pools. It also meant that whenever the city buses were crowded, African Americans had to give up seats in front to European Americans and move to the back of the bus.

One day on her way home from work Rosa was tired and sat down in the front of the bus. As the bus got crowded she was asked to give up her seat to a European American man, and she refused. The bus driver told her she had to go to the back of the bus, and she still refused to move. It was a hot day, she was tired and angry, and she became very stubborn.

The driver called a policeman, who arrested Rosa. When other African Americans in Montgomery heard this, they became angry too, so they decided to refuse to ride the buses until everyone was allowed to ride together. They boycotted the buses. The boycott, which was led by Martin Luther King Jr., succeeded. Now African Americans and European Americans can ride the buses together in Montgomery. Rosa Parks was a very brave person.

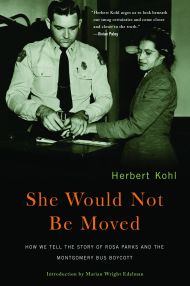

This story seems innocent enough. Rosa Parks is treated with respect, and the African American community is given credit for running the boycott and winning the struggle. On closer examination, however, this version reveals some distressing characteristics that serve to turn a carefully planned movement for social change into a spontaneous outburst based upon frustration and anger.

The following annotations on the previous summary suggest that we need a new story, one not only more in line with the truth but one that shows the organizational skills and determination of the African American community in Montgomery and the role of the bus boycott in the larger struggle to desegregate Montgomery and the South.

Why is this important?

When the story of the Montgomery bus boycott is told merely as a tale of a single heroic person, it leaves children hanging. Not everyone is a hero or heroine. Of course, the idea that only special people can create change is useful if you want to prevent mass movements and keep change from happening. Not every child can be a Rosa Parks, but everyone can imagine herself or himself as a participant in the boycott. As a tale of a social movement and a community effort to overthrow injustice, the Rosa Parks story opens the possibility of every child identifying herself or himself as an activist, as someone who can help make justice happen.

By Herbert Kohl, the author of more than forty books, including the bestselling classic 36 Children. A recipient of the National Book Award and the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, Herb Kohl was founder and first director of the Teachers & Writers Collaborative in New York City and established the PEN West Center in San Francisco, where he lives.

Very important and timely. Suggest using TeachingTolerance’s excellent video, “Children’s March” (free to teachers at http://www.teachingtolerance.org). They also have an excellent video re Rosa Parks which was out of print last time I checked and needs to be back in circulation.

Extraordinarily important discussion, lest we lose the heart and soul and meaning and signficance of the Civil Rights Movement, and of history in general.

As a middle school teacher I find Teaching Tolerance’s (free) “Mighty Times” videos to do an excellent job here. I showed “Children’s March” to my 6th-graders with wonderful results — the central actors were kids like them (I was one at the time) and the (unspoken) message is clearly that they, not some “great man,” are the key to the future. Teaching Tolerance’s similarly good DVD on Rosa Parks, unfortunately, is listed as “temporarily out of print.” Hope they get it back! http://www.tolerance.org/teaching-kits